A Bad Faith Reality

By Gabrielle Izu

May 2, 2023

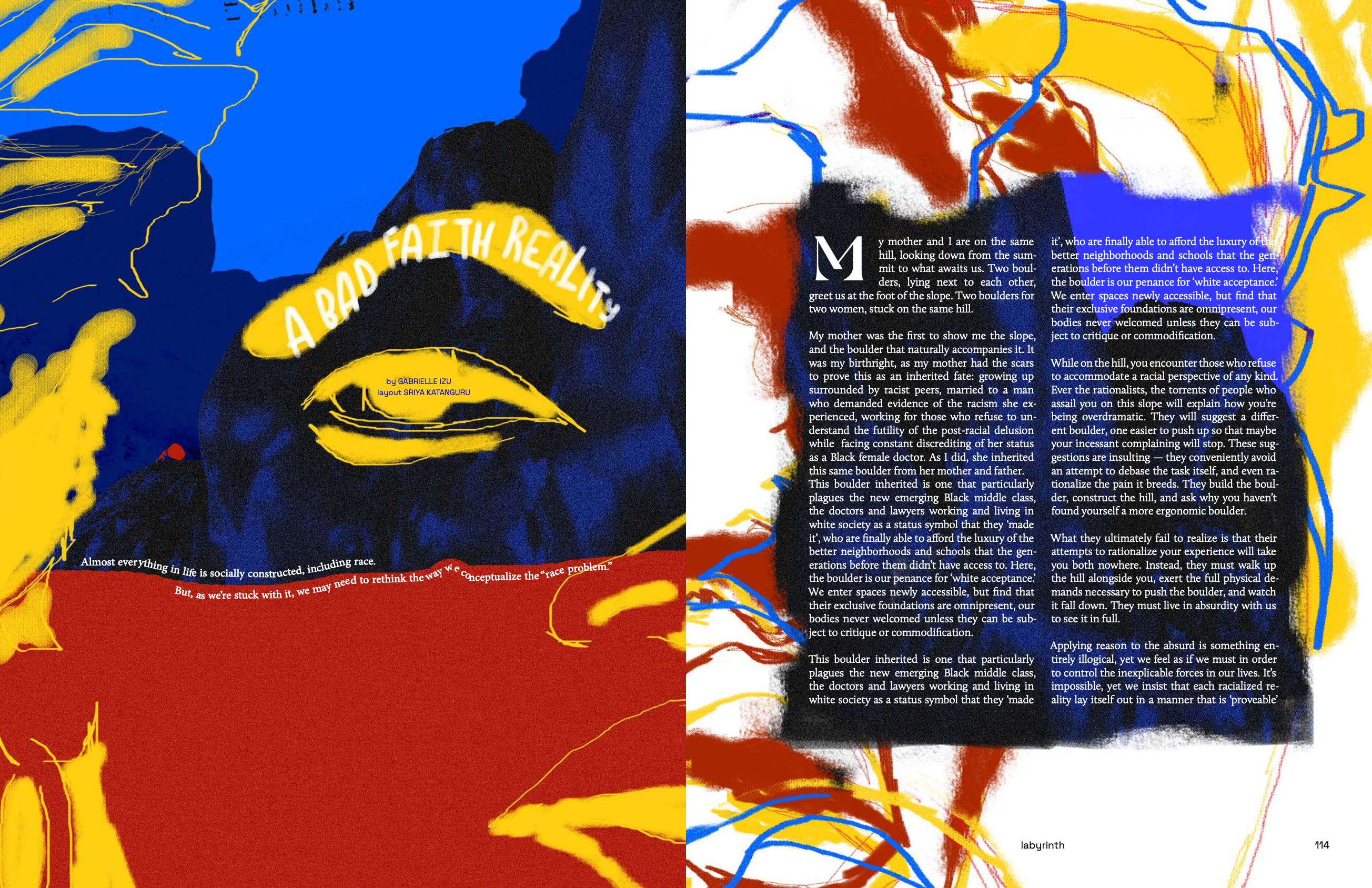

Almost everything in life is socially constructed, including race. But, as we’re stuck with it, we may need to rethink the way we conceptualize the “race problem.”

My mother and I are on the same hill, looking down from the summit to what awaits us. Two boulders, lying next to each other, greet us at the foot of the slope. Two boulders for two women, stuck on the same hill.

My mother was the first to show me the slope, and the boulder that naturally accompanies it. It was my birthright, as my mother had the scars to prove this as an inherited fate: growing up surrounded by racist peers, married to a man who demanded evidence of the racism she experienced, working for those who refuse to understand the futility of the post-racial delusion while facing constant discrediting of her status as a Black female doctor. As I did, she inherited this same boulder from her mother and father.

This boulder inherited is one that particularly plagues the new emerging Black middle class, the doctors and lawyers working and living in white society as a status symbol that they “made it”, who are finally able to afford the luxury of the better neighborhoods and schools that the generations before them didn’t have access to. Here, the boulder is our penance for “white acceptance.” We enter spaces newly accessible, but find that their exclusive foundations are omnipresent, our bodies never welcomed unless they can be subject to critique or commodification.

While on the hill, you encounter those who refuse to accommodate a racial perspective of any kind. Ever the rationalists, the torrents of people who assail you on this slope will explain how you’re being overdramatic. They will suggest a different boulder, one easier to push up so that maybe your incessant complaining will stop. These suggestions are insulting — they conveniently avoid an attempt to debase the task itself, and even rationalize the pain it breeds. They build the boulder, construct the hill, and ask why you haven’t found yourself a more ergonomic boulder.

What they ultimately fail to realize is that their attempts to rationalize your experience will take you both nowhere. Instead, they must walk up the hill alongside you, exert the full physical demands necessary to push the boulder, and watch it fall down. They must live in absurdity with us to see it in full.

![]()

Applying reason to the absurd is something entirely illogical, yet we feel as if we must in order to control the inexplicable forces in our lives. It’s impossible, yet we insist that each racialized reality lay itself out in a manner that is “proveable” — empirical, calculated, subject to peer review and eventual certification of the truth. Yet, like the Sisyphean task of Greek legend, this practice has no meaning. Nothing productive comes of it — no consensus, no definitive answer. Still, we demand the racial minority to strip themselves of the controversiality that has been imposed upon them and stand naked as we mull over what to do with their unwanted presence.

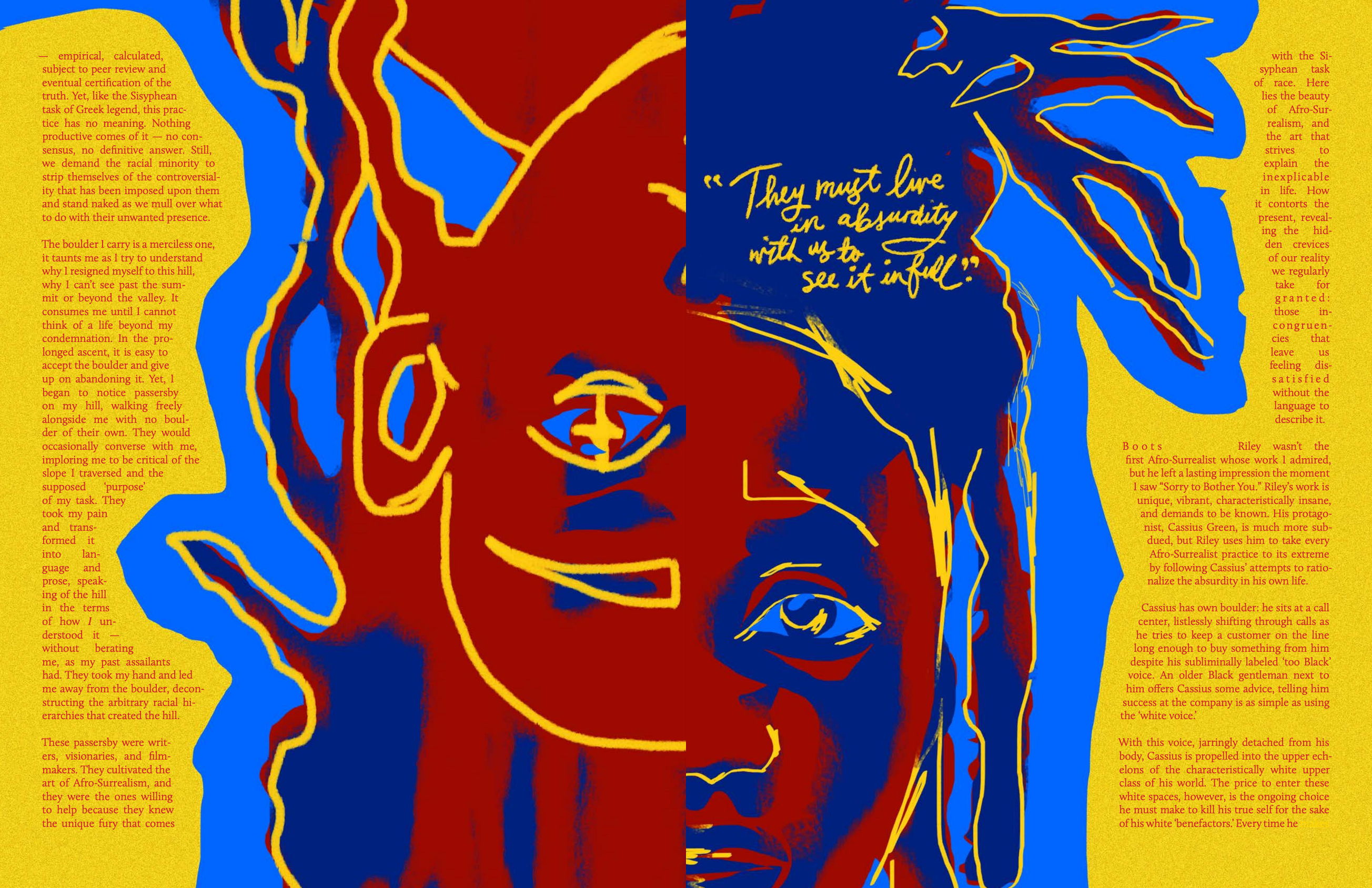

The boulder I carry is a merciless one, it taunts me as I try to understand why I resigned myself to this hill, why I can’t see past the summit or beyond the valley. It consumes me until I cannot think of a life beyond my condemnation. In the prolonged ascent, it is easy to accept the boulder and give up on abandoning it. Yet, I began to notice passersby on my hill, walking freely alongside me with no boulder of their own. They would occasionally converse with me, imploring me to be critical of the slope I traversed and the supposed “purpose” of my task. They took my pain and transformed it into language and prose, speaking of the hill in the terms of how I understood it — without berating me, as my past assailants had. They took my hand and led me away from the boulder, deconstructing the arbitrary racial hierarchies that created the hill.

These passersby were writers, visionaries, and filmmakers. They cultivated the art of Afro-Surrealism, and they were the ones willing to help because they knew the unique fury that comes with the Sisyphean task of race. Here lies the beauty of Afro-Surrealism, and the art that strives to explain the inexplicable in life. How it contorts the present, revealing the hidden crevices of our reality we regularly take for granted: those incongruencies that leave us feeling dissatisfied without the language to describe it.

Boots Riley wasn’t the first Afro-Surrealist whose work I admired, but he left a lasting impression the moment I saw “Sorry to Bother You.” Riley’s work is unique, vibrant, characteristically insane, and demands to be known. His protagonist, Cassius Green, is much more subdued, but Riley uses him to take every Afro-Surrealist practice to its extreme by following Cassius’ attempts to rationalize the absurdity in his own life.

Cassius has own boulder: he sits at a call center, listlessly shifting through calls as he tries to keep a customer on the line long enough to buy something from him despite his subliminally labeled “too Black” voice. An older Black gentleman next to him offers Cassius some advice, telling him success at the company is as simple as using the “white voice.”

With this voice, jarringly detached from his body, Cassius is propelled into the upper echelons of the characteristically white upper class of his world. The price to enter these white spaces, however, is the ongoing choice he must make to kill his true self for the sake of his white “benefactors.” Every time he makes this choice, he becomes more dissatisfied.

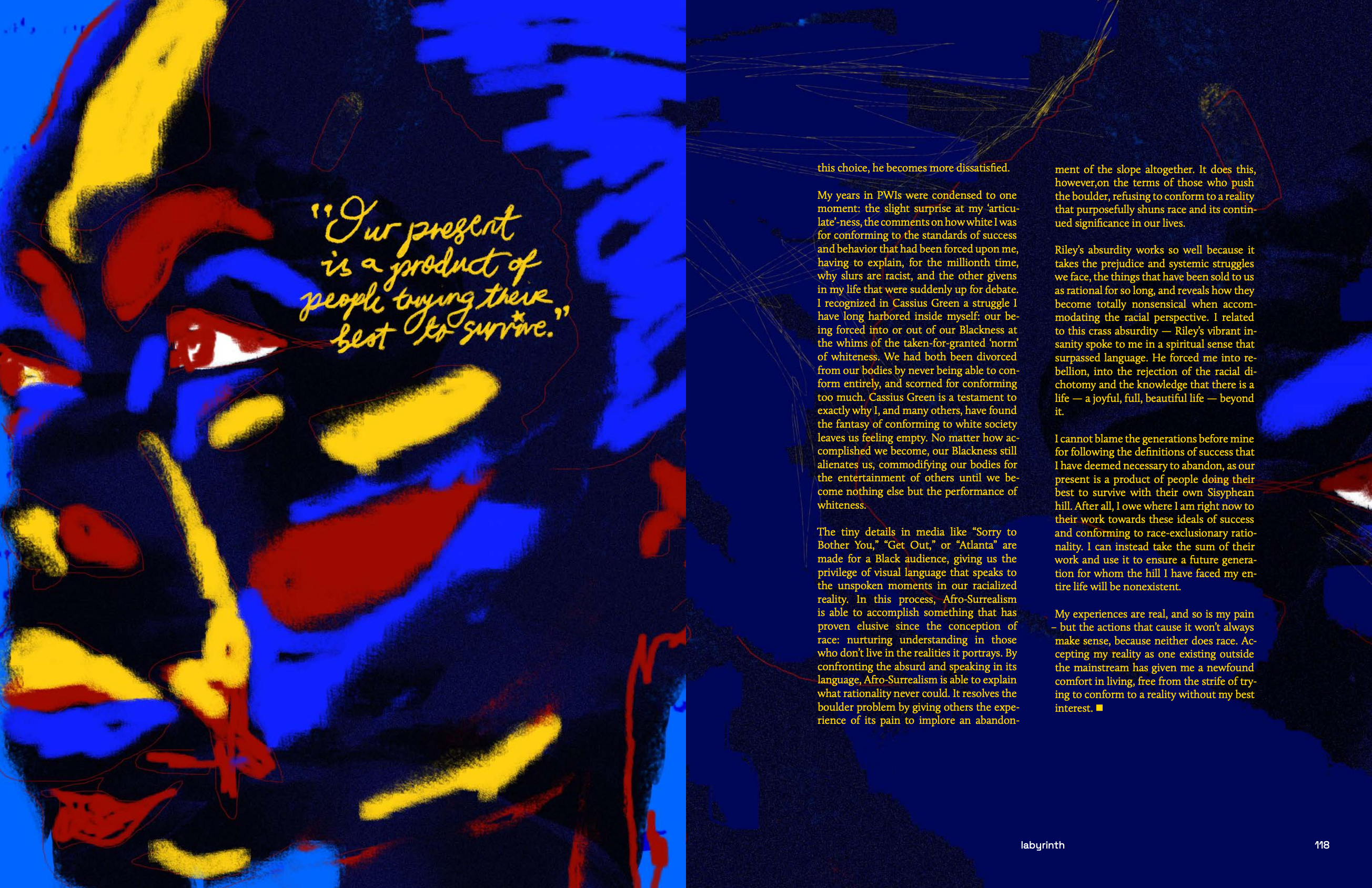

My years in PWIs were condensed to one moment: the slight surprise at my “articulate”-ness, the comments on how white I was for conforming to the standards of success and behavior that had been forced upon me, having to explain, for the millionth time, why slurs are racist, and the other givens in my life that were suddenly up for debate. I recognized in Cassius Green a struggle I have long harbored inside myself: our being forced into or out of our Blackness at the whims of the taken-for-granted “norm” of whiteness. We had both been divorced from our bodies by never being able to conform entirely, and scorned for conforming too much. Cassius Green is a testament to exactly why I, and many others, have found the fantasy of conforming to white society leaves us feeling empty. No matter how accomplished we become, our Blackness still alienates us, commodifying our bodies for the entertainment of others until we become nothing else but the performance of whiteness.

The tiny details in media like “Sorry to Bother You,” “Get Out,” or “Atlanta” are made for a Black audience, giving us the privilege of visual language that speaks to the unspoken moments in our racialized reality. In this process, Afro-Surrealism is able to accomplish something that has proven elusive since the conception of race: nurturing understanding in those who don’t live in the realities it portrays. By confronting the absurd and speaking in its language, Afro-Surrealism is able to explain what rationality never could. It resolves the boulder problem by giving others the experience of its pain to implore an abandonment of the slope altogether. It does this, however,on the terms of those who push the boulder, refusing to conform to a reality that purposefully shuns race and its continued significance in our lives.

Riley’s absurdity works so well because it takes the prejudice and systemic struggles we face, the things that have been sold to us as rational for so long, and reveals how they become totally nonsensical when accommodating the racial perspective. I related to this crass absurdity — Riley’s vibrant insanity spoke to me in a spiritual sense that surpassed language. He forced me into rebellion, into the rejection of the racial dichotomy and the knowledge that there is a life — a joyful, full, beautiful life — beyond it.

![]()

I cannot blame the generations before mine for following the definitions of success that I have deemed necessary to abandon, as our present is a product of people doing their best to survive with their own Sisyphean hill. After all, I owe where I am right now to their work towards these ideals of success and conforming to race-exclusionary rationality. I can instead take the sum of their work and use it to ensure a future generation for whom the hill I have faced my entire life will be nonexistent.

My experiences are real, and so is my pain – but the actions that cause it won’t always make sense, because neither does race. Accepting my reality as one existing outside the mainstream has given me a newfound comfort in living, free from the strife of trying to conform to a reality without my best interest. ■

My mother and I are on the same hill, looking down from the summit to what awaits us. Two boulders, lying next to each other, greet us at the foot of the slope. Two boulders for two women, stuck on the same hill.

My mother was the first to show me the slope, and the boulder that naturally accompanies it. It was my birthright, as my mother had the scars to prove this as an inherited fate: growing up surrounded by racist peers, married to a man who demanded evidence of the racism she experienced, working for those who refuse to understand the futility of the post-racial delusion while facing constant discrediting of her status as a Black female doctor. As I did, she inherited this same boulder from her mother and father.

This boulder inherited is one that particularly plagues the new emerging Black middle class, the doctors and lawyers working and living in white society as a status symbol that they “made it”, who are finally able to afford the luxury of the better neighborhoods and schools that the generations before them didn’t have access to. Here, the boulder is our penance for “white acceptance.” We enter spaces newly accessible, but find that their exclusive foundations are omnipresent, our bodies never welcomed unless they can be subject to critique or commodification.

While on the hill, you encounter those who refuse to accommodate a racial perspective of any kind. Ever the rationalists, the torrents of people who assail you on this slope will explain how you’re being overdramatic. They will suggest a different boulder, one easier to push up so that maybe your incessant complaining will stop. These suggestions are insulting — they conveniently avoid an attempt to debase the task itself, and even rationalize the pain it breeds. They build the boulder, construct the hill, and ask why you haven’t found yourself a more ergonomic boulder.

What they ultimately fail to realize is that their attempts to rationalize your experience will take you both nowhere. Instead, they must walk up the hill alongside you, exert the full physical demands necessary to push the boulder, and watch it fall down. They must live in absurdity with us to see it in full.

Applying reason to the absurd is something entirely illogical, yet we feel as if we must in order to control the inexplicable forces in our lives. It’s impossible, yet we insist that each racialized reality lay itself out in a manner that is “proveable” — empirical, calculated, subject to peer review and eventual certification of the truth. Yet, like the Sisyphean task of Greek legend, this practice has no meaning. Nothing productive comes of it — no consensus, no definitive answer. Still, we demand the racial minority to strip themselves of the controversiality that has been imposed upon them and stand naked as we mull over what to do with their unwanted presence.

The boulder I carry is a merciless one, it taunts me as I try to understand why I resigned myself to this hill, why I can’t see past the summit or beyond the valley. It consumes me until I cannot think of a life beyond my condemnation. In the prolonged ascent, it is easy to accept the boulder and give up on abandoning it. Yet, I began to notice passersby on my hill, walking freely alongside me with no boulder of their own. They would occasionally converse with me, imploring me to be critical of the slope I traversed and the supposed “purpose” of my task. They took my pain and transformed it into language and prose, speaking of the hill in the terms of how I understood it — without berating me, as my past assailants had. They took my hand and led me away from the boulder, deconstructing the arbitrary racial hierarchies that created the hill.

These passersby were writers, visionaries, and filmmakers. They cultivated the art of Afro-Surrealism, and they were the ones willing to help because they knew the unique fury that comes with the Sisyphean task of race. Here lies the beauty of Afro-Surrealism, and the art that strives to explain the inexplicable in life. How it contorts the present, revealing the hidden crevices of our reality we regularly take for granted: those incongruencies that leave us feeling dissatisfied without the language to describe it.

Boots Riley wasn’t the first Afro-Surrealist whose work I admired, but he left a lasting impression the moment I saw “Sorry to Bother You.” Riley’s work is unique, vibrant, characteristically insane, and demands to be known. His protagonist, Cassius Green, is much more subdued, but Riley uses him to take every Afro-Surrealist practice to its extreme by following Cassius’ attempts to rationalize the absurdity in his own life.

Cassius has own boulder: he sits at a call center, listlessly shifting through calls as he tries to keep a customer on the line long enough to buy something from him despite his subliminally labeled “too Black” voice. An older Black gentleman next to him offers Cassius some advice, telling him success at the company is as simple as using the “white voice.”

With this voice, jarringly detached from his body, Cassius is propelled into the upper echelons of the characteristically white upper class of his world. The price to enter these white spaces, however, is the ongoing choice he must make to kill his true self for the sake of his white “benefactors.” Every time he makes this choice, he becomes more dissatisfied.

My years in PWIs were condensed to one moment: the slight surprise at my “articulate”-ness, the comments on how white I was for conforming to the standards of success and behavior that had been forced upon me, having to explain, for the millionth time, why slurs are racist, and the other givens in my life that were suddenly up for debate. I recognized in Cassius Green a struggle I have long harbored inside myself: our being forced into or out of our Blackness at the whims of the taken-for-granted “norm” of whiteness. We had both been divorced from our bodies by never being able to conform entirely, and scorned for conforming too much. Cassius Green is a testament to exactly why I, and many others, have found the fantasy of conforming to white society leaves us feeling empty. No matter how accomplished we become, our Blackness still alienates us, commodifying our bodies for the entertainment of others until we become nothing else but the performance of whiteness.

The tiny details in media like “Sorry to Bother You,” “Get Out,” or “Atlanta” are made for a Black audience, giving us the privilege of visual language that speaks to the unspoken moments in our racialized reality. In this process, Afro-Surrealism is able to accomplish something that has proven elusive since the conception of race: nurturing understanding in those who don’t live in the realities it portrays. By confronting the absurd and speaking in its language, Afro-Surrealism is able to explain what rationality never could. It resolves the boulder problem by giving others the experience of its pain to implore an abandonment of the slope altogether. It does this, however,on the terms of those who push the boulder, refusing to conform to a reality that purposefully shuns race and its continued significance in our lives.

Riley’s absurdity works so well because it takes the prejudice and systemic struggles we face, the things that have been sold to us as rational for so long, and reveals how they become totally nonsensical when accommodating the racial perspective. I related to this crass absurdity — Riley’s vibrant insanity spoke to me in a spiritual sense that surpassed language. He forced me into rebellion, into the rejection of the racial dichotomy and the knowledge that there is a life — a joyful, full, beautiful life — beyond it.

I cannot blame the generations before mine for following the definitions of success that I have deemed necessary to abandon, as our present is a product of people doing their best to survive with their own Sisyphean hill. After all, I owe where I am right now to their work towards these ideals of success and conforming to race-exclusionary rationality. I can instead take the sum of their work and use it to ensure a future generation for whom the hill I have faced my entire life will be nonexistent.

My experiences are real, and so is my pain – but the actions that cause it won’t always make sense, because neither does race. Accepting my reality as one existing outside the mainstream has given me a newfound comfort in living, free from the strife of trying to conform to a reality without my best interest. ■

Layout: Sriya Katanguru

Other Stories in Labyrinth

© 2025 SPARK. All Rights Reserved.