A DREAM OF ONE’S OWN

May 2, 2023

Not our feminist figure. Not our Surrealist icon.

The sky is painted a wet, rainy gold on the day Frida Kahlo is impaled with a handrail. A streetcar, at full speed, slams into the bus she’s riding. Frida doesn’t immediately know to balk at the piece of iron shooting through her pelvis and spine; its severity doesn’t seem remarkable. She doesn’t even realize she is wounded until a bystander attempts to pull it from her. Her screams are so loud she drowns out the ambulance’s siren.

The accident leads her to a desert wasteland where her body matches the landscape. She paints “La Columna Rota” almost 20 years later, and she is the titular broken column. A pillar of the ionic order shoots through her center, holding her up but tearing her apart. Nails decorate her, reaching to embellish what is unbroken by bloody wounds. Frida thinks herself Jesus Christ nailed to the cross, or St. Sebastian, shot with arrows for his faith: she’s a saint, a martyr, holy in her pain. She cries, yet stares down her viewer with knowing eyes, asking them to acknowledge her hurt and revere her for living through it. At just 18 years old, she has deemed herself an immortal sufferer, a Sisyphus to be worshiped.

Though she wishes she were well, she won’t let go of her injury, if only for the sake of her art. She is no goddess to pray to. Frida is just a person, a person with a debilitating injury and a paintbrush who chooses all the wrong things, and copes in all the wrong ways. When tragedy crawls to her, she delves deeper into it. The battle in her blood cells, between sickness and health, inspires her. It consumes her. It becomes her.

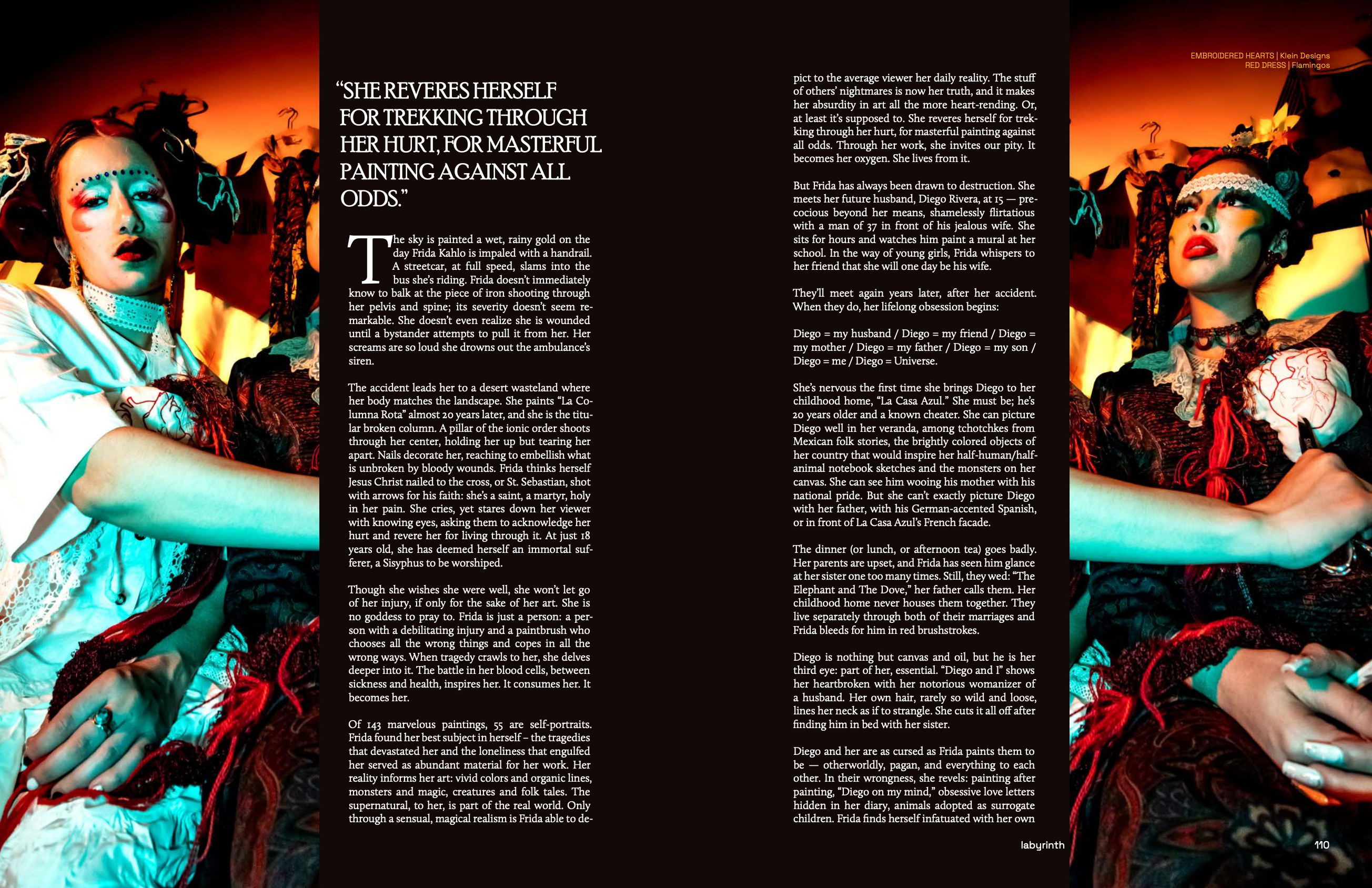

Of 143 marvelous paintings, 55 are self-portraits. Frida found her best subject in herself – the tragedies that had devastated her and the loneliness that engulfed her served as abundant material for her work. Her reality informs her art: vivid colors and organic lines, monsters and magic, creatures and folk tales. The supernatural, to her, is part of the real world. Only through a sensual, magical realism is Frida able to depict to the average viewer her daily reality. The stuff of others' nightmares is now her truth, and it makes her absurdity in art all the more heart-rending. Or, at least it’s supposed to. She reveres herself for trekking through her hurt, for masterful painting against all odds. Through her work, she invites our pity. It becomes her oxygen. She lives from it.

![]()

But Frida has always been drawn to destruction. She meets her future husband, Diego Rivera, at 15 — precocious beyond her means, shamelessly flirtatious with a man of 37 in front of his jealous wife. She sits for hours and watches him paint a mural at her school. In the way of young girls, Frida whispers to her friend that she will one day be his wife.

They’ll meet again years later, after her accident. When they do, her lifelong obsession begins:

Diego = my husband / Diego = my friend / Diego = my mother / Diego = my father / Diego = my son / Diego = me / Diego = Universe.

She’s nervous the first time she brings Diego to her childhood home, “La Casa Azul.” She must be; he’s 20 years older and a known cheater. She can picture Diego well in her veranda, among tchotchkes from Mexican folk stories, the brightly colored objects of her country that would inspire her half-human/half-animal notebook sketches and the monsters on her canvas. She can see him wooing his mother with his national pride. But she can’t exactly picture Diego with her father, with his German-accented Spanish, or in front of La Casa Azul’s French facade.

The dinner (or lunch, or afternoon tea) goes badly. Her parents are upset, and Frida has seen him glance at her sister one too many times. Still, they wed: “The Elephant and The Dove,” her father calls them. Her childhood home never houses them together. They live separately through both of their marriages and Frida bleeds for him in red brushstrokes.

Diego is nothing but canvas and oil, but he is her third eye: part of her, essential. “Diego and I” shows her heartbroken with her notorious womanizer of a husband. Her own hair, rarely so wild and loose, lines her neck as if to strangle. She cuts it all off after finding him in bed with her sister.

Diego and her are as cursed as Frida paints them to be — otherworldly, pagan, and everything to each other. In their wrongness, she revels: painting after painting, “Diego on my mind,” obsessive love letters hidden in her diary, animals adopted as surrogate children. Frida finds herself infatuated with her own suffering. Her and Diego’s tumultuousness doesn’t deter her from continuing their relationship; it encourages her. She remains with him for years in their own twisted form of love.

As much as her heart breaks, she’ll cheat too. She’s nothing to look up to, this Frida. She sleeps with Leon Trotsky, whom Diego brought into his house for safety from extradition near the end of their marriage. She obsesses over Joseph Stalin, painting “Stalin and I” after his several thousand murders are revealed. She writes about the men and women she loves next to “mi Diego” in her diary. Her independence fell in the face of romanticization, at men of power and creativity. Her character faltered when it came to her idols.

She wakes one morning and across from her in bed is herself. “The Two Fridas,” she whispers, two mirror images of herself, as different as they are replicas. A thin vein wraps around two versions of herself, connecting European Frida, who is trying to stanch the bleeding of her torn heart, to Mexican Frida, who is in traditional Tehuana dress and holding a photo of Diego. Both are somber, but only Mexican Frida is healed. She is who Diego wants: a fellow Mexican muralist, a good woman with a sensible mind and healthy creativity. European Frida holds forceps to clamp her vein, but blood still spoils her clean white dress and their marital bed.

She’s neither and she’s both, torn between her worlds: Mexican or not, Diego’s or not, healthy or not. She’s somewhere in between.The Two Fridas join hands, but still, she bleeds.

![]()

In her storied life, there is no perfect Mexican artist or American capitalist icon. There is no broken body or healthy figure. There is no feminist symbol or “wife of Diego Rivera.” She is a study in duality, a question of faith. Frida’s own self is the art—wrought by tragedy, shaped by injury, and finally, encased in paint. She is devastated, so she turns to art instead, painting as a catharsis just as the Surrealists did. But she was never interested in being part of their movement. She painted from her life, not dreams and latent feelings in these dreams as the Surrealist title would have suggested. She’s a deer shot to death in the woods, a mangled body held up by a column, thorns piercing into her neck. Her monsters don’t remain on canvas or come from her unconscious: they lie with her in hospital bed and home.

Her words are cruel, crude. She knows she is selfish, she knows she is unkind, and still, she is an artist. She sits, holding hands, staring into your soul. She bleeds, yet stares. She looks at you, however, and sees herself. She sees Diego, she sees Mexico. She sees dreams, and nightmares, and she’s haunted by that this is all, somehow, while she’s awake. ■

The sky is painted a wet, rainy gold on the day Frida Kahlo is impaled with a handrail. A streetcar, at full speed, slams into the bus she’s riding. Frida doesn’t immediately know to balk at the piece of iron shooting through her pelvis and spine; its severity doesn’t seem remarkable. She doesn’t even realize she is wounded until a bystander attempts to pull it from her. Her screams are so loud she drowns out the ambulance’s siren.

The accident leads her to a desert wasteland where her body matches the landscape. She paints “La Columna Rota” almost 20 years later, and she is the titular broken column. A pillar of the ionic order shoots through her center, holding her up but tearing her apart. Nails decorate her, reaching to embellish what is unbroken by bloody wounds. Frida thinks herself Jesus Christ nailed to the cross, or St. Sebastian, shot with arrows for his faith: she’s a saint, a martyr, holy in her pain. She cries, yet stares down her viewer with knowing eyes, asking them to acknowledge her hurt and revere her for living through it. At just 18 years old, she has deemed herself an immortal sufferer, a Sisyphus to be worshiped.

Though she wishes she were well, she won’t let go of her injury, if only for the sake of her art. She is no goddess to pray to. Frida is just a person, a person with a debilitating injury and a paintbrush who chooses all the wrong things, and copes in all the wrong ways. When tragedy crawls to her, she delves deeper into it. The battle in her blood cells, between sickness and health, inspires her. It consumes her. It becomes her.

Of 143 marvelous paintings, 55 are self-portraits. Frida found her best subject in herself – the tragedies that had devastated her and the loneliness that engulfed her served as abundant material for her work. Her reality informs her art: vivid colors and organic lines, monsters and magic, creatures and folk tales. The supernatural, to her, is part of the real world. Only through a sensual, magical realism is Frida able to depict to the average viewer her daily reality. The stuff of others' nightmares is now her truth, and it makes her absurdity in art all the more heart-rending. Or, at least it’s supposed to. She reveres herself for trekking through her hurt, for masterful painting against all odds. Through her work, she invites our pity. It becomes her oxygen. She lives from it.

But Frida has always been drawn to destruction. She meets her future husband, Diego Rivera, at 15 — precocious beyond her means, shamelessly flirtatious with a man of 37 in front of his jealous wife. She sits for hours and watches him paint a mural at her school. In the way of young girls, Frida whispers to her friend that she will one day be his wife.

They’ll meet again years later, after her accident. When they do, her lifelong obsession begins:

Diego = my husband / Diego = my friend / Diego = my mother / Diego = my father / Diego = my son / Diego = me / Diego = Universe.

She’s nervous the first time she brings Diego to her childhood home, “La Casa Azul.” She must be; he’s 20 years older and a known cheater. She can picture Diego well in her veranda, among tchotchkes from Mexican folk stories, the brightly colored objects of her country that would inspire her half-human/half-animal notebook sketches and the monsters on her canvas. She can see him wooing his mother with his national pride. But she can’t exactly picture Diego with her father, with his German-accented Spanish, or in front of La Casa Azul’s French facade.

The dinner (or lunch, or afternoon tea) goes badly. Her parents are upset, and Frida has seen him glance at her sister one too many times. Still, they wed: “The Elephant and The Dove,” her father calls them. Her childhood home never houses them together. They live separately through both of their marriages and Frida bleeds for him in red brushstrokes.

Diego is nothing but canvas and oil, but he is her third eye: part of her, essential. “Diego and I” shows her heartbroken with her notorious womanizer of a husband. Her own hair, rarely so wild and loose, lines her neck as if to strangle. She cuts it all off after finding him in bed with her sister.

Diego and her are as cursed as Frida paints them to be — otherworldly, pagan, and everything to each other. In their wrongness, she revels: painting after painting, “Diego on my mind,” obsessive love letters hidden in her diary, animals adopted as surrogate children. Frida finds herself infatuated with her own suffering. Her and Diego’s tumultuousness doesn’t deter her from continuing their relationship; it encourages her. She remains with him for years in their own twisted form of love.

As much as her heart breaks, she’ll cheat too. She’s nothing to look up to, this Frida. She sleeps with Leon Trotsky, whom Diego brought into his house for safety from extradition near the end of their marriage. She obsesses over Joseph Stalin, painting “Stalin and I” after his several thousand murders are revealed. She writes about the men and women she loves next to “mi Diego” in her diary. Her independence fell in the face of romanticization, at men of power and creativity. Her character faltered when it came to her idols.

She wakes one morning and across from her in bed is herself. “The Two Fridas,” she whispers, two mirror images of herself, as different as they are replicas. A thin vein wraps around two versions of herself, connecting European Frida, who is trying to stanch the bleeding of her torn heart, to Mexican Frida, who is in traditional Tehuana dress and holding a photo of Diego. Both are somber, but only Mexican Frida is healed. She is who Diego wants: a fellow Mexican muralist, a good woman with a sensible mind and healthy creativity. European Frida holds forceps to clamp her vein, but blood still spoils her clean white dress and their marital bed.

She’s neither and she’s both, torn between her worlds: Mexican or not, Diego’s or not, healthy or not. She’s somewhere in between.The Two Fridas join hands, but still, she bleeds.

In her storied life, there is no perfect Mexican artist or American capitalist icon. There is no broken body or healthy figure. There is no feminist symbol or “wife of Diego Rivera.” She is a study in duality, a question of faith. Frida’s own self is the art—wrought by tragedy, shaped by injury, and finally, encased in paint. She is devastated, so she turns to art instead, painting as a catharsis just as the Surrealists did. But she was never interested in being part of their movement. She painted from her life, not dreams and latent feelings in these dreams as the Surrealist title would have suggested. She’s a deer shot to death in the woods, a mangled body held up by a column, thorns piercing into her neck. Her monsters don’t remain on canvas or come from her unconscious: they lie with her in hospital bed and home.

Her words are cruel, crude. She knows she is selfish, she knows she is unkind, and still, she is an artist. She sits, holding hands, staring into your soul. She bleeds, yet stares. She looks at you, however, and sees herself. She sees Diego, she sees Mexico. She sees dreams, and nightmares, and she’s haunted by that this is all, somehow, while she’s awake. ■

Layout: Camille Chuduc

Photographer: Olivia Caesar

Stylists: Isabel Sitar & Summer Sweeris

HMUA: Angelynn Rivera & Adreanna Alvarez

Models: Arliz Muñoz & Natan Murillo

Photographer: Olivia Caesar

Stylists: Isabel Sitar & Summer Sweeris

HMUA: Angelynn Rivera & Adreanna Alvarez

Models: Arliz Muñoz & Natan Murillo

Other Stories in Labyrinth

© 2025 SPARK. All Rights Reserved.