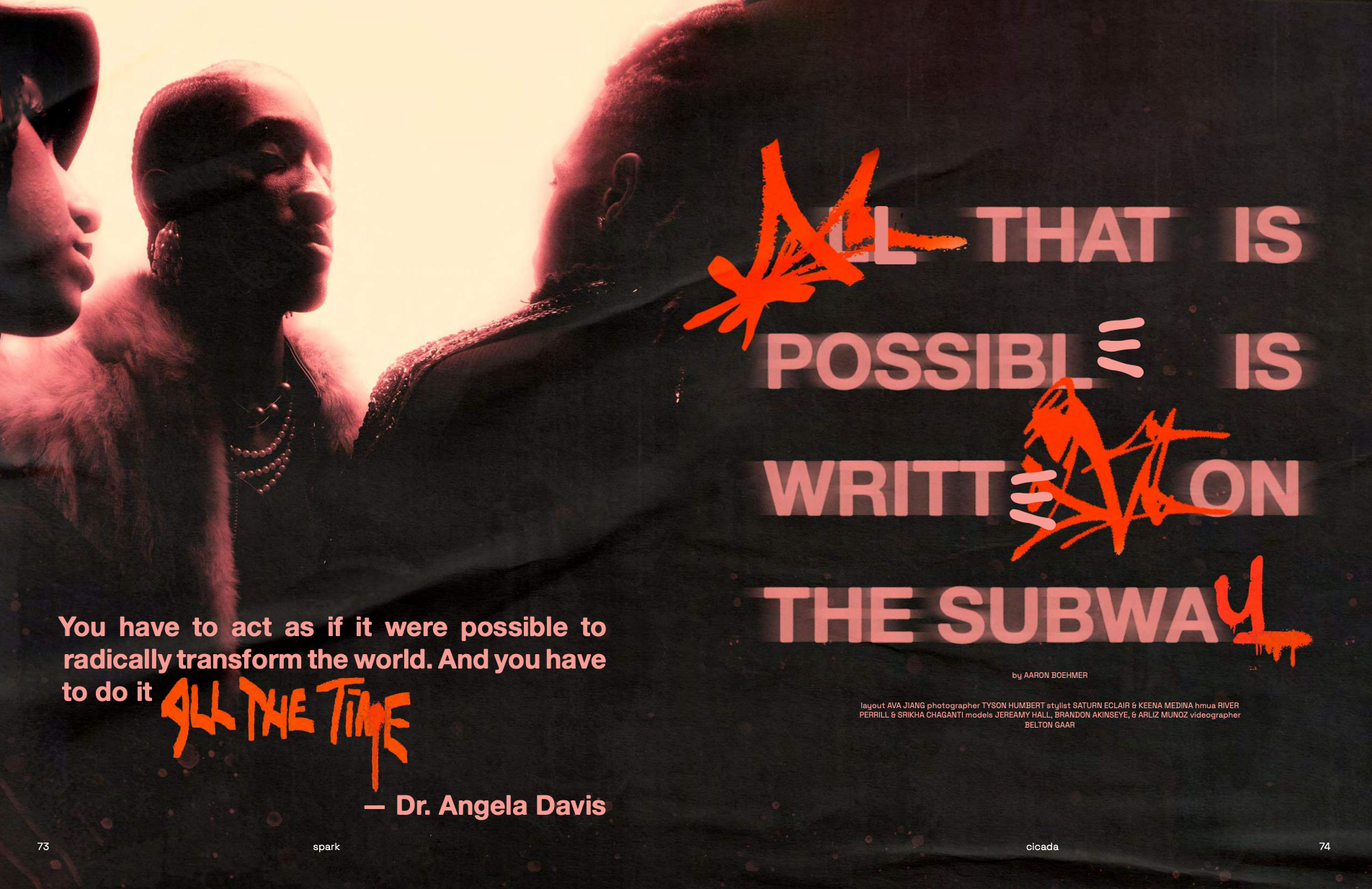

ALL THAT IS POSSIBLE IS WRITTEN ON THE SUBWAY

January 17, 2024

You have to act as if it were possible to radically transform the world. And you have to do it all the time.

— Dr. Angela Davis

Everything is possible right here, right now, at this moment. Move quickly while the cops are distracted. This moment is fleeting. The girl in the railyard, the boy on the subway — they have a vision of the city in their heads and a can of spray paint in their hands. They’re ready to tear down and rebuild. They’re making the city in their own image. They’re the Graffiti writers drafting a new living document, and it reads: Democracy is written in spray paint poetry.

We can’t do anything alone that’s worth it. Everything that is worthwhile is done with other people.

— Mariame Kaba

Since Graffiti’s birth in the 1970s, New Yorkers have been tagged with surveillance.

Under the public’s sun, the New York Mayor says he’s in love — with this city, with its people, with you. Closed, dim-lit doors whisper the opposite. Slip a hand inside, unlock the latch, and you will see him kissing the lips of tyranny like the cop that he is — sloppy mouthed and dressed in navy blue.

Rudy Giuliani formed the Anti-Graffiti Task Force in 1995. His goal: finally eradicate Graffiti from New York. His predecessors — Dinkins, Koch, Beame, Lindsay — tried to do this, and his successors — Bloomberg, de Blasio, Adams — are still trying again and again. Ban spray paint and large markers for minors. Line the subway yards with razor-wire and dog patrols. Infiltrate the scene with undercover cops. Conjure false narratives. Propagandize. Crack down. Declare war.

This story, like most, is about power. When do people and systems justify wielding it, and when is the use of power labeled criminal? Who uses power to control, and who, instead, uses it to reimagine, rebuild, and then gives it away freely?

Since John Lindsay declared war in 1972, the Graffiti writer has been delegitimized with new names — vandal, thug, criminal. This is not a coincidence. The pioneering Graffiti writers were mostly Black and brown teenagers. As Dr. Angela Davis points out, the United States’ collective imagination fantasizes about labeling Black and brown people as “evildoers” and “criminals.” The war on Graffiti was another measure to surveil these communities — to police their creativity, to expand the prison industrial complex, and to never once ask why the Graffiti writer wanted to reimagine — to reclaim — the city in the first place. What could possibly be wrong with this perfect, beautiful city?

And so, the Graffiti writer has but this moment. Before long, this moment will die between the teeth and tongue of a sloppy mouth. With the cops distracted, the Graffiti writer takes this moment by the hands and runs.

We need rebellion in our society. We need someone to question the status quo.

— Lady Pink

It’s 1979. The coming decades belong to the Graffiti writer. 15-year-old Lady Pink enters the scene this year. She’s a feminist and she doesn’t know it yet.

She’s not yet going by the name Lady Pink when she meets Seen TC5, a classmate close in age. He’s the leader of TC5, or The Cool 5, a crew at the forefront of New York’s blossoming Graffiti scene. She wants in.

It takes months of convincing; the Graffiti scene, like the world, is not clean of misogyny. She gives TC5 an opportunity to redefine the scene — to open it up, to be the only Graffiti crew with a girl. Eventually, finally, they budge: she’s in. All that’s left is her tag. Seen wants everyone to know that TC5 has a girl in the group.

“This is your name now,” he tells her: Pink. No guy would dare write “Pink” as their tag — “too girly.” It was more or less understood that if she used “Pink,” everyone would know she is the girl — the First Lady of Graffiti.

And so, the sun finds a break in the clouds and Pink dubs herself Lady Pink. With her title, Pink makes certain she’s not the last lady in Graffiti, establishing an all-women crew called Ladies of the Arts in 1980.

As she makes her way back home to Queens, she spots her work decorating the subway trains; she spots the marks she’s made on a city that now belongs to her.

It's not just a boys’ club. We have a sisterhood thing going.

— Lady Pink

Throughout the 1980s and 90s, she paints with the best of the best. She runs in the same circles as legends — Fab 5 Freddy, CRASH, DAZE, DONDI, Basquiat, Rammellzee — because she is one. As the new century takes hold, Pink continues to collaborate with other legendary women artists, take part in solo exhibitions and mural projects, and visit schools to teach students about the power of art and community.

Yet, despite some level of mainstream acceptance, authorities crack down. In the 1990s, a former Neptune Meter factory becomes world-renowned for the art on its walls. By the early 2000s, the building owner, Jerry Wolkoff, hires Graffiti writer Meres One as curator, who transforms the structure into a Graffiti mecca called 5 Pointz — named after the five boroughs of New York City.

In 2007, Pink creates a mural for the space, and in 2013, her art — along with over two decades’ worth of work by other Graffiti legends — is whitewashed and wiped clean overnight. By 2014, 5 Pointz is completely demolished. In its place, thanks to a money-hungry landlord like Wolkoff, stands a high-rise residential building. He’s eventually ordered to pay $6.7 million in damages after facing a lawsuit by 21 artists whose work had been destroyed — one of those artists being Lady Pink.

It’s the Graffiti writer vs. an entire system. Their success is smothered by sloppy mouths, driven out by gentrification, and broken down by surveillance as the war on Graffiti bludgeons on. But Rammellzee often thinks about war and weapons that can be used against it.

You think war is always shooting and beating everybody, but no, we had the letters fight for us.

— RAMM:ΣLL:ZΣΣ

A few years before 1979, Rammellzee enters the scene. He is many things: a philosopher, a performance artist, a Hip Hop musician, a Gothic Futuristic Graffiti writer. To reclaim the alphabet, to arm letters, to place Graffiti and Hip Hop into a racialized, working-class movement against capitalism, white supremacy, and the West is Rammellzee’s aim.

I’m going to finish the war. I’m going to assassinate the infinity sign.

— RAMM:ΣLL:ZΣΣ

Graffiti is symbolic, interdimensional warfare; Rammellzee sees himself a 20th century monk illuminating the manuscripts of a new world. He tells everyone about this war — that Graffiti writers’ reactions will turn more and more iconoclastic, so long as the writers are ready. Everyone including another big name in the art world: Jean-Michel Basquiat.

Introduced to Basquiat by Fab 5 Freddy, a founding architect of Graffiti and a Hip Hop pioneer, the two soon become friends, collaborators, and rivals. Despite what Rammellzee and Basquiat’s relationship leads to — iconic paintings like Hollywood Africans (1983) and music records like “Beat Box” — it’s complicated. One of Rammellzee’s main issues is that he believes the art industry and its conspiring markets have turned Basquiat into a product. According to Rammellzee, the market labels Basquiat’s abstract paintings as “Graffiti,” undermining the actual writers who take to the trains to create true Graffiti — from tags and throw-ups to burners and wildstyle, covering whole cars from back-to-back, end-to-end, top-to-bottom. Rammellzee calls Basquiat a liar, a know-it-all, just short of a sell-out, and less than a friend.

Whether Rammellzee meant this to be a personal attack on Basquiat or not isn’t relevant. His issue reflects the nature of New York’s war on Graffiti. It’s about how the establishment — the market, the police, the New York Mayor, the white public — does whatever it wants to Black and brown artists. It commodifies and condemns. It whitewashes and erases. It creates foes of former collaborators. It conjures into existence things that were never there to begin with.

The market turned Basquiat into a Graffiti product, a poster child pre-and post-death. But, despite his undeniable influence within and contributions to the scene, Basquiat never claimed to be a Graffiti writer.

I wanted to be a star, not a gallery mascot.

— Jean-Michel Basquiat

This story, like most, is about power. The New York Mayor spits on the face of Graffiti in the same breath that he asks: What could possibly be wrong with this perfect, beautiful city?

He knows what’s wrong, which is why he asks the wrong question rhetorically.

Having the truth written on the walls is too revealing for him, for the establishment, for the police, for the white public. It is too real, too democratic. If the communities that were born in this city, grew up in this city, built this city, imbued this city with magic and culture were allowed to paint this city in their own image, what might happen next?

Might they take the city that rightfully belonged to them back? Might they expand their power and unseat the Mayor? Might they hope and dream? Might they rebuild their neighborhoods? Might they imagine beyond the colonial project of the United States?

It’s 1979, it’s 2013, it’s 2023, and the coming decades belong to the Graffiti writer. Tagged with surveillance, the writer has but this moment.

On the way to the subway, they ask the right question: What could be made possible, what could be made beautiful in this imperfect city?

Write it in a new living document — across train cars and brick walls, inside tunnels and under bridges — so the whole city, the whole world can see it, read it, and feel it.

Anything and everything you can imagine — right here, right now, in this moment. ■

Layout: Ava Jiang

Photographer: Tyson Humbert

Stylists: Saturn Eclair & Keena Medina

HMUA: River Perrill & Srikha Chaganti

Models: Jereamy Hall, Brandon Akinseye & Arliz Munoz

Videographer: Belton Gaar

Other Stories in Cicada

© 2025 SPARK. All Rights Reserved.