Asphalt

By Danielle Yampuler

December 8, 2024

| The city only loves its sons. |

My city has known me my whole life but it has never said a word to me. I want to know what it has seen. I wish it’d tell me what it thought. I wish it’d say anything at all.

The city is Gaia, a cruel mother who births the monsters I must face. These monsters bloom from the flesh of my city, the concrete and asphalt from which Houston is made. They are the men who scream at me, who follow me down sidewalks and roads — the ones who stare at me with odd smiles that warp their faces.

I see him remolded, over and over, in the shape of people who view me as an “it” rather than an “I.” They’re all made from the stuff that seeps into the concrete and gets spewed back out. Broken glass shards from beer bottles, cigarette ash tapped off into the street, murky flood water, they all eventually make their way into the asphalt. Then they are conceived into an entirely different body with, as far as I’m concerned, the exact same soul.

When they are not there, I can feel the cement pulsing. The sidewalks and roads feel warm to the touch, a living organism, always ready to pull the next monster from its womb.

Once, it birthed a dingy red sports car with a man at its wheel.

His car slowed down until it matched my pace on the cracked sidewalk. I was one small stretch of asphalt from my home, but I knew I could not escape this. He initiated the dance and I responded in turn, our moves well practiced. I had never met him before and I knew everything about him.

“You should get into my car,” he stated. It was more of a demand than a question.

The car continuously let out a low growl, a predator. I walked quickly and did my best not to make eye contact.

“C’mon. I can take you anywhere you want to go,” he prodded.

Traffic moved around his car like it was a pothole. The sidewalk held its breath beneath me. I hoped that it was worrying for me, but maybe it was only trying not to laugh.

I responded, “I’m alright. I’m sixteen.”

“That’s okay, baby. Just get in.”

I said nothing and walked faster. It was a useless move. The sidewalk opened up and he parked right between where I was and where I needed to go. He begged me to get in. I couldn’t walk around his car — I had no clue if he would ram right through me if given the option. I could imagine droplets like rubies on the pavement, my body mangled by tires. I wasn’t sure if this man saw much difference between touching and disfiguring.

I looked at him. He was screaming. He looked like the man who chased me through a parking lot when I was fourteen, and only left after I hid behind a car. He looked like the man who put his arms around my best friend and me so he could grope her non-existent chest when we were twelve. He looked like so many people, and I couldn’t piece his face together anymore. It looked melted, deformed. I think my staring unnerved him. He went silent, scoffed, and drove away.

I saw myself, lying still and bloody in the road. The sidewalk refused to swallow her and instead implanted her in my mind. For the remainder of the walk, I saw my gore as clearly as I would have had she got up, cracked her limbs back into place, and walked me home herself. The pavement watched me stumble and lent no help. It never has.

These types of people are always someone new molded from something very old, older than the city itself. I couldn’t walk down the street of my home without a scream from a car or a comment from someone. They did not care who I was, how I looked. It didn’t matter how I changed or carried myself. What I wore only affected the frequency of the comments.

They will always find something to say, miniskirt or cargo pants. It made me angry as a high-schooler when my mom would tell me to cover up — my clothing felt inconsequential because they would act just the same. I refused to understand her. I saw her worry as a way to stifle my creativity, to make the world just a bit more against me.

This changed the summer after my freshman year of college. My friend and I were back in town, and we went to an all-ages show in a dilapidated bar. We chose to stay in the parking lot with the vendors and the smokers, the bands inside were too loud. It was dark, and the air smelled like tobacco. The faint thrumming of guitar interspersed with the occasional crashes of a cymbal could be heard. The asphalt below our feet breathed softly, like it was resting.

We came across two beautiful girls. After a moment of talking to them, we realized they were freshman in high school. We had assumed they were our age and suddenly saw them in a new light. They wore outfits as revealing as our own. I felt a fear for them that I couldn’t quite identify just then. After they left, she and I found an empty patch of road to sink to.

The asphalt was damp, the way Houston always is. We could feel the wetness through our thin clothing. We tried to talk, but every topic felt trivial and tapered off into silence. During an especially long pause, I watched my friend fidget with the fabric of her short skirt. She took a deep breath, then looked into my eyes.

“They were only, like, fifteen,” she said, and I understood.

I knew they would receive attention no matter what they wore, but if I could get them to become prey for one less man born from sediment, then I would’ve felt better.

“I feel scared for them. It feels stupid, I want them to cover up. I want them to be able to dress however they’d like, but I also want them to cover up and never be anywhere that anyone can see them ever again,” I ranted.

“Yeah. Like, we may be in danger too, but we can deal with it,” she remarked.

“They probably also can. They shouldn’t have to,” I responded.

“We shouldn’t have to, either.”

I giggle at this, and she joins in. It devolves into hysterical-drunk-girl laughs, then sobs. Our worry was spilling out onto the tarmac. We wanted to save the unsavable. I felt the cruel eyes of the concrete that raised me, that watched me grow up. I questioned it in the same way I question God: why would an all-powerful, all-seeing being not just fucking help me?

Eventually, we calmed down. A man walked up to us, sat down, tried to make small talk. He had stubble on his chin, he looked too old to be there. He flirted with me, but subtly enough that I couldn’t shut him down immediately. If I did that, he could call me a rude bitch. My friend showed me her phone screen: she called an Uber for us. He asked for my number, I told him I wasn’t interested. He grumbled and walked away, then our car arrived. We left.

“I know you’re eighteen and legal and all. But I feel like he didn’t check and wouldn’t have cared had you not been,” she said, and I vehemently agreed.

The next day, his face was all over the social media of my scene friends, informing everyone that he was a known pedophile and not to be trusted. I felt guilt for feeling satisfied that we were correct about him. I was glad he talked to me, and not those girls.

But there is no saving them — or me. To be “saved” is only to delay an inevitable understanding of what will always be true. I could dress up or down. I could hide behind cars and hold onto the pepper spray in my pocket. I could walk as quickly as I wanted, but the real damage would be done regardless: I would never feel safe in my home. The truth is that the city which had raised me was not for me: the pavement did its bidding and those it birthed were its pawns. I could grow up in one place my whole life and it will never belong to me, to those girls.

It will forever stay silent, holding its breath when I need it most. It will allow me to go wherever I need, as long as it can torment me along the way. My city has known me my whole life and it will never do a thing for me.

In the end, I could only outgrow it. Once you begin to look like a woman instead of a girl, the pavement becomes disinterested. It stops spitting out nearly as many men at you. You cannot help those it goes after next. I know this. Regardless, I still wish to lay down and put my ear to the pavement, to beg it to have something to say. I can imagine the breathing of the stone against my body, up and down.

I could spend the rest of my life asking the concrete to explain itself. My home will stay as silent as ever. ■

Layout: Yubin Kim

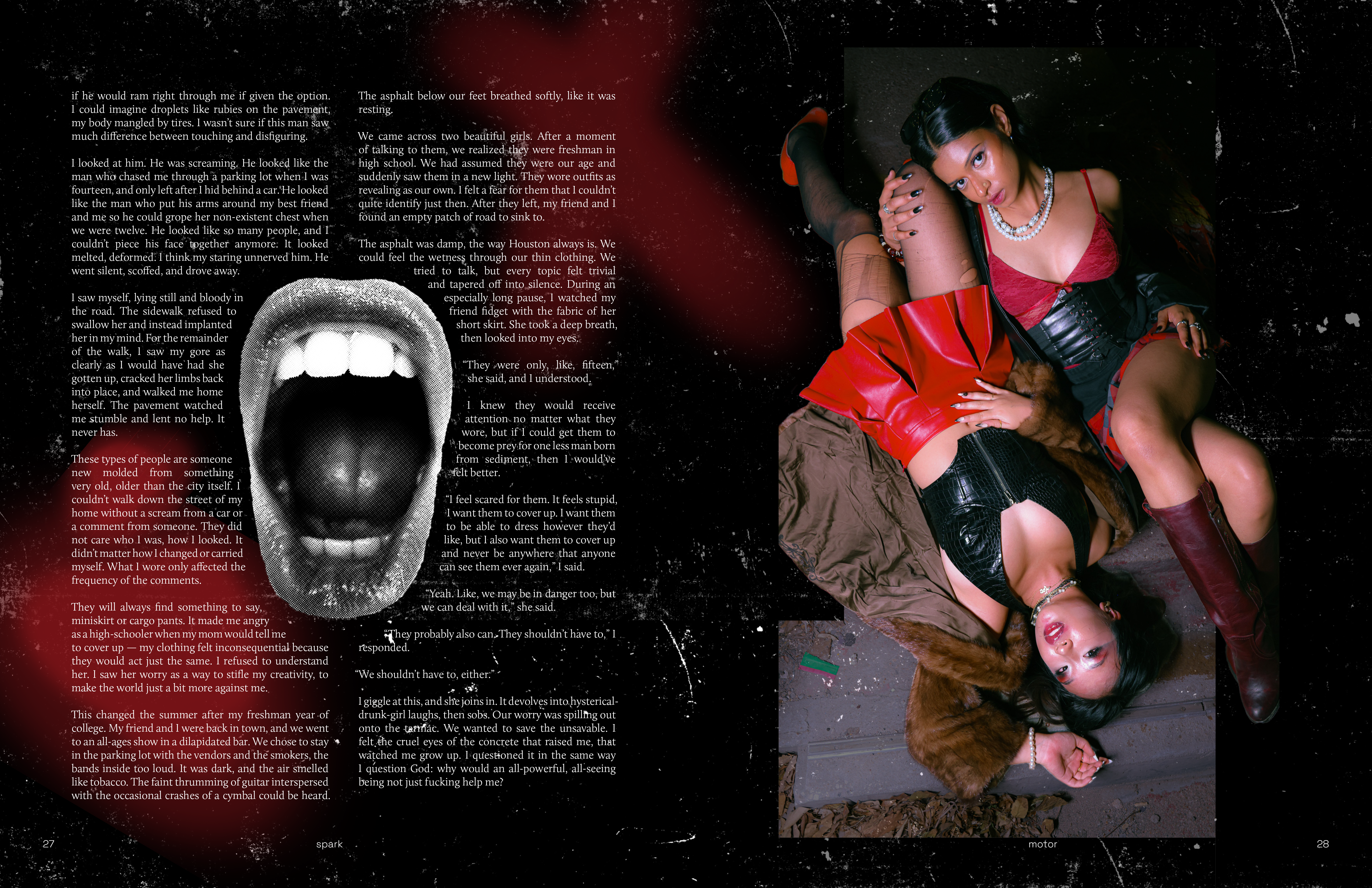

Photographer: Nicole Howard

Stylists: Natalie Salinas & Jennifer Le

HMUA: Floriana Hool

Nail Artist: Ruby Walker

Models: Tasmuna Omar & Elaine Gong

Other Stories in Motor

© 2025 SPARK. All Rights Reserved.