Death is Life

By Rupak Kadiri

January 24, 2024

There exists a sect of outcasts that seem to straddle between spiritual and material realms, whose practices are horrifying to some, divine to others.

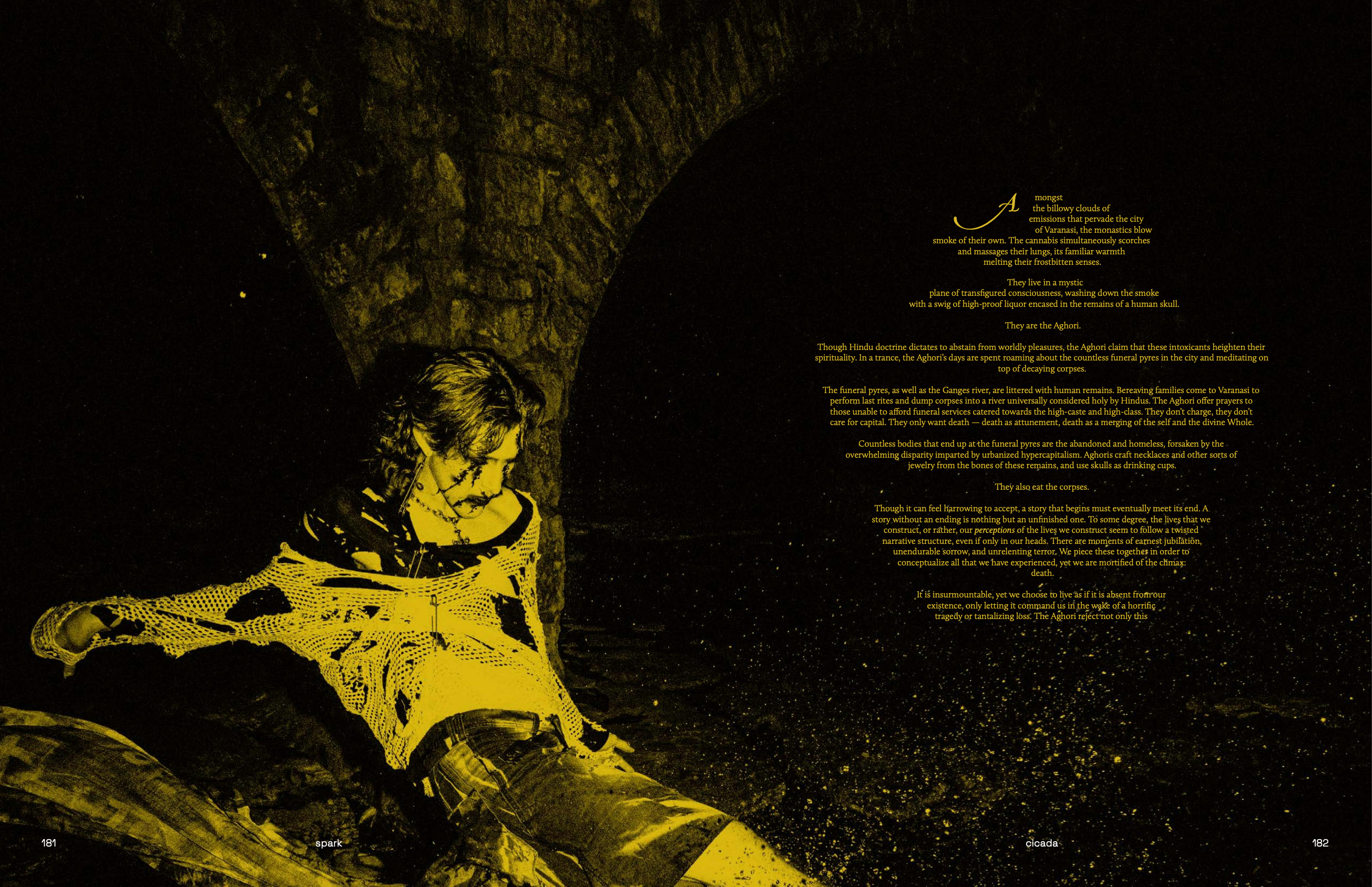

Amongst the billowy clouds of emissions that pervade the city of Varanasi, the monastics blow smoke of their own. The cannabis simultaneously scorches and massages their lungs, its familiar warmth melting their frostbitten senses. They live in a mystic plane of transfigured consciousness, washing down the smoke with a swig of high-proof liquor encased in the remains of a human skull.

They are the Aghori.

Though Hindu doctrine dictates to abstain from worldly pleasures, the Aghori claim that these intoxicants heighten their spirituality. In a trance, the Aghori’s days are spent roaming about the countless funeral pyres in the city and meditating on top of decaying corpses.

The funeral pyres, as well as the Ganges river, are littered with human remains. Bereaving families come to Varanasi to perform last rites and dump corpses into a river universally considered holy by Hindus. The Aghori offer prayers to those unable to afford funeral services catered towards the high-caste and high-class. They don’t charge, they don't care for capital. They only want death — death as attunement, death as a merging of the self and the divine Whole.

Countless bodies that end up at the funeral pyres are the abandoned and homeless, forsaken by the overwhelming disparity imparted by urbanized hypercapitalism. Aghoris craft necklaces and other sorts of jewelry from the bones of these remains, and use skulls as drinking cups.

They also eat the corpses.

Though it can feel harrowing to accept, a story that begins must eventually meet its end. A story without an ending is nothing but an unfinished one. To some degree, the lives that we construct, or rather, our perceptions of the lives we construct seem to follow a twisted narrative structure, even if only in our heads. There are moments of earnest jubilation, unendurable sorrow, and unrelenting terror. We piece these together in order to conceptualize all that we have experienced, yet we are mortified of the climax: death.

It is insurmountable, yet we choose to live as if it is absent from our existence, only letting it command us in the wake of a horrific tragedy or tantalizing loss. The Aghori reject not only this condemnation of death, but the materialistic posturing of our lives. It is all an illusory diversion in their eyes. They maintain that these “stories of our lives” are total fabrications; birth is not the beginning, death is not the end, and our lives are not our lives.

The Aghori are a specific sect of Hinduism and are known as shaivas, or worshippers of the deity Shiva, the Lord of Destruction. Ethnocentric Westerners are quick to label their practices as "Satanic," though the Aghori know nothing of this concept. In some ways, such ill-conceived notions are fated to arise: the philosophies of the Aghori present a drastic departure from the consumerist maxims of Western life. High-caste and high-class members of Indian society also hold disdain for the Aghori, maintaining their conventional practices as the only feasible ones.

None of these outsiders mean anything to the Aghori – neither does money, power, or material amenities. Their name comes from the Sanskrit term aghora, or roughly, “entering light from dark.” They believe their human lives to be mere illusions distracting us from the Oneness of the universe. The sense of our independent self is nothing but a sense, for there is no difference between self and other, between man and God. We are all manifestations of an individual divine power, regrettably deluded into perceiving ourselves as ourselves. Death, reviled and detested, is the catalyst for us to reach Oneness — to escape our fragmentation and reach Wholeness.

Jarring yet emblematic, this act is an evocative denouncement of worldly desire, an act in which the consumer becomes consumed. It is a liberating practice, underscoring the distance of the Aghori from the intrinsic greed of humanity. Something as repudiated as a piece of a corpse is consumed as a means of sustenance. It is treated simply as that.

At the same time, this ritual not only contradicts the norms of Indian civilization, but of civilization entirely. Not unlike the other practices of the Aghori, social norms do not influence the practices necessary to attain their spiritual destination. Practically all religious parties adhere to their belief because they believe it to be the one and only truth, and the Aghori are no exception.

In their eyes, desire is inseparable from human nature. By rejecting desire, they reject their own humanity, granting them absolution from reincarnation. Their apathy is a principle akin to their faith, if not even more significant. Suffering is intertwined with life and life is intertwined with suffering, so why should anything be done to erase it, rather than erasing notions of life itself? How these practices comprise this erasure is unclear to many, but it makes more sense than anything else to the Aghori, who make the conscious decision to enter this oath: to be numb is to be independent of any source of delight or affliction, any source of love, hatred, anger, envy, lust, fear, disgust, and most significant of all, any source of desire.

And to be numb is to be immune from existence, and whatever happens outside of it. ■

Layout: Binny Bae

Photographer: Thomas Cruz

Stylists: Elsa Zhang & Vivian Moyers

HMUA: Audrey Hoff

Models: Aiden Crowl & Victoria Hales

Other Stories in Cicada

© 2025 SPARK. All Rights Reserved.