FANGIRL

By Safa Michigan

May 2, 2023

You mean so much to me. You mean everything to me. You have no idea I exist.

I inherited my love of The Beatles from my mother, who regularly played their compilation album “1” when I was younger. I think they wrote beautiful, compelling songs about love and loss that transcend space and time. They’ve even soundtracked many critical phases of my life. We’ve taken Beatles-themed tours of London and Liverpool, and we collect kitschy memorabilia. We’re definitely fans.

In January, I drove home to Shreveport so my mother and I could attend a show by a tribute band called Liverpool Legends. I learned they were hand-picked by George Harrison’s sister Louise to honor her brother, which meant they had to be good, but I didn’t expect the startlingly uncanny resemblance their physical appearances and voices held to those of the actual band. I surprised myself by sobbing and even screaming, especially when the George impersonator played the famed guitar solo in “While My Guitar Gently Weeps.”

Part of the show’s set design was a projection of video clips I recognized as footage of Beatlemania. The clips were black and white scenes of total madness, colored by uninhibited desperation not entirely sure of what it desired. Girls and women waiting outside venues and hotels screamed, sobbed, and fainted, bewildering security personnel and the media.

“This is Beatleland, formerly known as Britain, where an epidemic named Beatlemania has taken over the teenage population,” a newscaster in one of the clips said.

![]()

Watching the girls, I wanted to scream, too. In my teenage years, I could’ve been one of them. I’m confident I would’ve been hopelessly sick with Beatlemania in the ‘60s. I understand why they screamed. I know fangirling doesn’t exist in a vacuum.

In its disastrous wake, World War II left a fractured geopolitical scheme. The psychological trauma of the war, the apocalyptic power of the atom bomb, and the desperation of capitalists, colonizers, and imperialists to maintain their hegemony infused the world, particularly the West, with a deeply entrenched paranoia. In Britain and America, the 1950s introduced the teenager as a social category. British youth navigated conservative culture, economic anxiety, and fear of an arms race. In America, those in power produced a culture defined by hypernationalism, conservative and traditional values, and the nuclear family. With their long hair and soft facial features, The Beatles represented the possibility of rejecting conformity, embracing joy, and living an authentic life.

Within two years of their formation, the band left behind their working class neighborhoods in Liverpool to embrace nationwide fame. A year later, Beatlemania reached America, and 73 million people tuned into their 1964 performance on “The Ed Sullivan Show.” When asked what he thought about American fans, John Lennon responded, “They’re the wildest.” During their 1965 concert at New York's Shea Stadium, the band couldn’t hear themselves perform over the cacophony of screams.

At first, this was what they wanted; as they knew fangirls are fueled by the glimmer of hope that their favorite might notice them someday, The Beatles directly addressed their young female audience with songs like “Love Me Do” and “I Want to Hold Your Hand.” Fame and attention quickly exhausted them, though. Most mortals (un)fortunate enough to taste deification cannot withstand its weight. Within six years, The Beatles had become global superstars on a scale no one could have warned them about — because they were the first. Partly due to fear for their own safety, the band made the decision to stop touring for good.

Male writers, psychologists, and political analysts held female Beatlemaniacs in pejorative contempt; to them, these girls were crazy, dull, useless, stupid failures. I think these critics feared unbridled feminine emotion, and I think some of them were just jealous. I also believe American Studies professor Allison McCracken’s theory that fangirls are positioned at odds with white male masculinity, which demands emotions always be kept in check, controlled and stifled. She believes fangirls’ emotional excess represents an association with those on the margins of society, including working-class people, people of color, and of course, teenage girls.

![]()

The Beatles’ young female fans became the architects of their own dreamlands that would free them from the strangulation of the cultural repression that demanded their docility and their dullness. Their screams, tears, fainting spells, and energetic heartbeats were a collective performance of somatic resistance to social control.

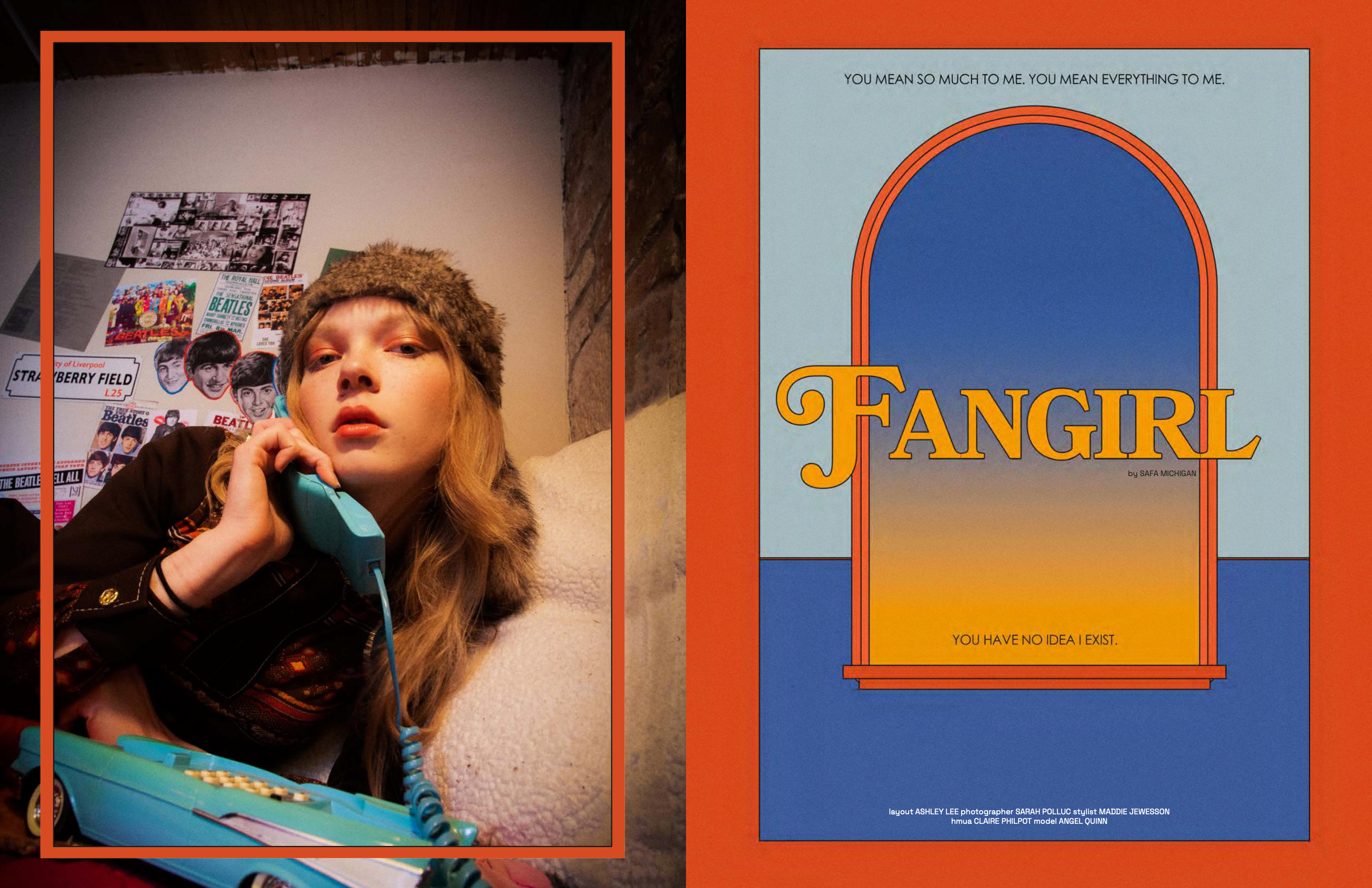

The stereotypical fangirl is a female teenager with a wall full of posters of her favorite boy bands and male pop stars. Back in the ’60s, she waited for The Beatles outside venues and hotels, screaming and crying, holding a hand-painted sign proclaiming her love. She always had the radio on and tuned into every television performance (if she wasn’t able to be there in person, standing for hours in a mile-long queue). She was Jan Myers, who descended into the sewers of northwest London one day in October 1965 with the objective of crawling her way under Abbey Road Studios, where The Beatles were recording their last album “Rubber Soul.” A couple years prior, Jan had skipped school to ride her bike 20 miles to Heathrow Airport so she could personally welcome the band home to England.

In the twenty-first century, the stereotypical fangirl isn’t too different from her ancestor, but she has the Internet, which altered temporality forever and awarded her the illusion of constant access to her favorite. The fangirl is a force in the fandom’s online community. She has 10k followers on Instagram, 50k on Twitter, and 100k on TikTok. She reads (or even writes) fanfiction. She is Your/Name. She imagines and consumes until her obsession consumes her, and she screams. I was her once. Like Jan, I know what it’s like to love something more than myself while working through great uncertainty about my place in the world.

I was a sensitive child, always more emotional than my peers and consistently obsessive about social interactions gone wrong, perceived abandonments, and whoever my crush of the week happened to be. I was an even more sensitive teenager. I tried hard to make people understand me, but they didn’t.

Teenage girlhood is a greatly lonely thing. I think we all learned our own unique set of survival skills, whether from our mothers, older sisters or cousins, literature, or media. The coping mechanisms that grounded me the most firmly were reading, writing, and music. Fangirling allowed me to combine all of these mechanisms into one dreamy escape.

My teenage obsessions with One Direction, Taylor Swift, and alternative and indie groups never compelled me to crawl through sewers. Instead, I crawled through Twitter threads, YouTube rabbit holes, and Tumblr blog archives. If my favorite artists posted, I begged them to notice me in the replies. Sometimes they did, and I felt whole. I stayed up until 4 a.m. chatting with other fans. I wrote fanfiction I’ll never share with anyone. I left school early the day Zayn left the band. Home alone, I collapsed to the floor and cried when the “Live While We’re Young” music video premiered. At that moment, I wasn’t signaling my fangirl status to anyone else. I was experiencing a moment of somatic release. Fangirling is performance, but it’s also primal.

Participation in fandom is also racialized and classed. I was able to buy CDs, posters, vinyls, and sweatshirts, and I’m privileged enough to have seen One Direction when I was 12, Harry Styles solo when I was 18, and Taylor Swift twice. Then there’s Hailey Baldwin, whose white, wealthy, and famous pedigree shaped her into the final boss of fangirls. Her antics as a diehard Belieber are well-documented in the media, but ultimately, she won, didn’t she? She got to marry the object of her reverence, the person behind the illusion she’d long ago convinced herself was the love of her life. It’s an inspiring tale.

![]()

That the musicians we love become objects of worship isn’t entirely illogical. Music is a profoundly personal, vulnerable medium. We project onto our favorite musical artists. They become vessels that hold the excess love we were never taught to deal with, and we lose a little bit of ourselves in the process. Some even lose a lot of themselves. By venerating celebrities, we set ourselves up for disappointment when they revoke our access to them.

As dangerous as it can be, fangirling is also beautiful, sacred, and here to stay. The institutions that drive fangirls to madness haven’t changed much since the ’60s. The world is still on fire. Capitalism, patriarchy, misogyny, and imperialism, among other systems our generation has inherited, aren't withering away anytime soon.

In the face of this doom, fangirls are a community of people who understand each other, which can be a life-saving resource in a lonely, hard, and increasingly dystopian time. They liberate themselves through emotional catharsis, take control of their sexual agency, and make friends along the way. Above all, they scream for a reason. We should all listen. ■

I inherited my love of The Beatles from my mother, who regularly played their compilation album “1” when I was younger. I think they wrote beautiful, compelling songs about love and loss that transcend space and time. They’ve even soundtracked many critical phases of my life. We’ve taken Beatles-themed tours of London and Liverpool, and we collect kitschy memorabilia. We’re definitely fans.

In January, I drove home to Shreveport so my mother and I could attend a show by a tribute band called Liverpool Legends. I learned they were hand-picked by George Harrison’s sister Louise to honor her brother, which meant they had to be good, but I didn’t expect the startlingly uncanny resemblance their physical appearances and voices held to those of the actual band. I surprised myself by sobbing and even screaming, especially when the George impersonator played the famed guitar solo in “While My Guitar Gently Weeps.”

Part of the show’s set design was a projection of video clips I recognized as footage of Beatlemania. The clips were black and white scenes of total madness, colored by uninhibited desperation not entirely sure of what it desired. Girls and women waiting outside venues and hotels screamed, sobbed, and fainted, bewildering security personnel and the media.

“This is Beatleland, formerly known as Britain, where an epidemic named Beatlemania has taken over the teenage population,” a newscaster in one of the clips said.

Watching the girls, I wanted to scream, too. In my teenage years, I could’ve been one of them. I’m confident I would’ve been hopelessly sick with Beatlemania in the ‘60s. I understand why they screamed. I know fangirling doesn’t exist in a vacuum.

In its disastrous wake, World War II left a fractured geopolitical scheme. The psychological trauma of the war, the apocalyptic power of the atom bomb, and the desperation of capitalists, colonizers, and imperialists to maintain their hegemony infused the world, particularly the West, with a deeply entrenched paranoia. In Britain and America, the 1950s introduced the teenager as a social category. British youth navigated conservative culture, economic anxiety, and fear of an arms race. In America, those in power produced a culture defined by hypernationalism, conservative and traditional values, and the nuclear family. With their long hair and soft facial features, The Beatles represented the possibility of rejecting conformity, embracing joy, and living an authentic life.

Within two years of their formation, the band left behind their working class neighborhoods in Liverpool to embrace nationwide fame. A year later, Beatlemania reached America, and 73 million people tuned into their 1964 performance on “The Ed Sullivan Show.” When asked what he thought about American fans, John Lennon responded, “They’re the wildest.” During their 1965 concert at New York's Shea Stadium, the band couldn’t hear themselves perform over the cacophony of screams.

At first, this was what they wanted; as they knew fangirls are fueled by the glimmer of hope that their favorite might notice them someday, The Beatles directly addressed their young female audience with songs like “Love Me Do” and “I Want to Hold Your Hand.” Fame and attention quickly exhausted them, though. Most mortals (un)fortunate enough to taste deification cannot withstand its weight. Within six years, The Beatles had become global superstars on a scale no one could have warned them about — because they were the first. Partly due to fear for their own safety, the band made the decision to stop touring for good.

Male writers, psychologists, and political analysts held female Beatlemaniacs in pejorative contempt; to them, these girls were crazy, dull, useless, stupid failures. I think these critics feared unbridled feminine emotion, and I think some of them were just jealous. I also believe American Studies professor Allison McCracken’s theory that fangirls are positioned at odds with white male masculinity, which demands emotions always be kept in check, controlled and stifled. She believes fangirls’ emotional excess represents an association with those on the margins of society, including working-class people, people of color, and of course, teenage girls.

The Beatles’ young female fans became the architects of their own dreamlands that would free them from the strangulation of the cultural repression that demanded their docility and their dullness. Their screams, tears, fainting spells, and energetic heartbeats were a collective performance of somatic resistance to social control.

The stereotypical fangirl is a female teenager with a wall full of posters of her favorite boy bands and male pop stars. Back in the ’60s, she waited for The Beatles outside venues and hotels, screaming and crying, holding a hand-painted sign proclaiming her love. She always had the radio on and tuned into every television performance (if she wasn’t able to be there in person, standing for hours in a mile-long queue). She was Jan Myers, who descended into the sewers of northwest London one day in October 1965 with the objective of crawling her way under Abbey Road Studios, where The Beatles were recording their last album “Rubber Soul.” A couple years prior, Jan had skipped school to ride her bike 20 miles to Heathrow Airport so she could personally welcome the band home to England.

In the twenty-first century, the stereotypical fangirl isn’t too different from her ancestor, but she has the Internet, which altered temporality forever and awarded her the illusion of constant access to her favorite. The fangirl is a force in the fandom’s online community. She has 10k followers on Instagram, 50k on Twitter, and 100k on TikTok. She reads (or even writes) fanfiction. She is Your/Name. She imagines and consumes until her obsession consumes her, and she screams. I was her once. Like Jan, I know what it’s like to love something more than myself while working through great uncertainty about my place in the world.

I was a sensitive child, always more emotional than my peers and consistently obsessive about social interactions gone wrong, perceived abandonments, and whoever my crush of the week happened to be. I was an even more sensitive teenager. I tried hard to make people understand me, but they didn’t.

Teenage girlhood is a greatly lonely thing. I think we all learned our own unique set of survival skills, whether from our mothers, older sisters or cousins, literature, or media. The coping mechanisms that grounded me the most firmly were reading, writing, and music. Fangirling allowed me to combine all of these mechanisms into one dreamy escape.

My teenage obsessions with One Direction, Taylor Swift, and alternative and indie groups never compelled me to crawl through sewers. Instead, I crawled through Twitter threads, YouTube rabbit holes, and Tumblr blog archives. If my favorite artists posted, I begged them to notice me in the replies. Sometimes they did, and I felt whole. I stayed up until 4 a.m. chatting with other fans. I wrote fanfiction I’ll never share with anyone. I left school early the day Zayn left the band. Home alone, I collapsed to the floor and cried when the “Live While We’re Young” music video premiered. At that moment, I wasn’t signaling my fangirl status to anyone else. I was experiencing a moment of somatic release. Fangirling is performance, but it’s also primal.

Participation in fandom is also racialized and classed. I was able to buy CDs, posters, vinyls, and sweatshirts, and I’m privileged enough to have seen One Direction when I was 12, Harry Styles solo when I was 18, and Taylor Swift twice. Then there’s Hailey Baldwin, whose white, wealthy, and famous pedigree shaped her into the final boss of fangirls. Her antics as a diehard Belieber are well-documented in the media, but ultimately, she won, didn’t she? She got to marry the object of her reverence, the person behind the illusion she’d long ago convinced herself was the love of her life. It’s an inspiring tale.

That the musicians we love become objects of worship isn’t entirely illogical. Music is a profoundly personal, vulnerable medium. We project onto our favorite musical artists. They become vessels that hold the excess love we were never taught to deal with, and we lose a little bit of ourselves in the process. Some even lose a lot of themselves. By venerating celebrities, we set ourselves up for disappointment when they revoke our access to them.

As dangerous as it can be, fangirling is also beautiful, sacred, and here to stay. The institutions that drive fangirls to madness haven’t changed much since the ’60s. The world is still on fire. Capitalism, patriarchy, misogyny, and imperialism, among other systems our generation has inherited, aren't withering away anytime soon.

In the face of this doom, fangirls are a community of people who understand each other, which can be a life-saving resource in a lonely, hard, and increasingly dystopian time. They liberate themselves through emotional catharsis, take control of their sexual agency, and make friends along the way. Above all, they scream for a reason. We should all listen. ■

Layout: Ashley Lee

Photographer: Sarah Polluc

Stylist: Maddie Jewesson

HMUA: Claire Philpot

Model: Angel Quinn

Photographer: Sarah Polluc

Stylist: Maddie Jewesson

HMUA: Claire Philpot

Model: Angel Quinn

Other Stories in Labyrinth

© 2025 SPARK. All Rights Reserved.