I’ve never been stung by a bee

January 24, 2024

Yet I feared their presence and their sting.

I had a language with my dad that only we spoke. I’ll try to translate.

He told me that gardening healed a part of him and that dancing let him express it. He showed me every side of him: his engineer brain, his poems, and the books he gifted me on my birthdays. If I couldn’t sleep at night, he would make me tea and let me borrow something to read. He taught me that bees are very gentle if you let them know you’re their friend. When he got sick, he said that he spoke to his cancer the way he spoke to the bees, and hoped that it wouldn’t hurt him.

My dad’s illness spanned my freshman year of high school to my first year of college. It was a rollercoaster of health and disease, chemo and radiation, and hopes for a remission that never came. In his initial diagnosis, the doctors told him he had months to live. It seemed true — his body became so frail that I didn’t think he would ever look like my dad again. His round stomach deflated and his tan skin turned translucent. Running into family friends became torment when they would comment on his sunken cheeks and sagging jeans.

I wanted to scream, I wanted to cry, I wanted to hide. I wanted to crawl into the grave right next to him. At the same time, I wanted to hear him climb up the stairs to tuck me into bed again. I wanted him to have gray hair and glasses and dance with me at my wedding. There were too many memories to hold onto and too many hopes to let go of.

There were times between his diagnosis and death when he didn’t even look sick. He grew confident he could beat it and I grew comfortable he would always be there. But cyclically, the cancer reminded us it wasn’t a silent killer. I laid in a dorm bed while he lay in a hospital and called me to tell me it was time to come home.

How would I fit the next 40 years of my life that he’d miss into one conversation? I formulated a plan for what I needed to say to him on my three hour drive from Austin to Dallas. But when it was my turn to take a seat on the vinyl couch next to his bed, he was too tired to hear any of it. We spent those last few days tip toeing around death, hoping that if we were quiet enough it might retreat.

In my all-consuming grief, I’ve scoured for signs that I still have access to my dad. Now that he’s gone, I find his letters tucked between pages in poetry books. I read them often because I’m ravenous for his words, to hear the dying language of our relationship. I visit the river where we spread his ashes each year on the anniversary of his death and I cry. In those vulnerable moments — the water still with his memories — a bee will follow me around. It’ll land on my arm or leg and I’m not afraid.

I’ve never been stung by a bee. Even as a child, when I spoke too loud and ran too fast, they never bothered me, but they were always there. At that time, my parents were still married. I had my brother and sister, very few worries, and a rainbow rug on the floor of my room. My friends were other happy children, who my mom organized play dates and small groups with. Connor was one of these friends.

His parents sold a house to my mom and dad on Lincolnshire Drive, and they became our neighbors. At our playgroup, my brother, Connor, and I would play with sticks in the backyard. They were our swords and our light sabers. If it was warm, we would run around in our swimsuits with the sprinklers on and cannonball into the pool.

When Connor was four, the doctors found tumors in his spine, heart, and abdomen. He was diagnosed with stage IV neuroblastoma and died four years later.

Connor was the first person I ever lost. My brother and I visited him in the colorful, sterile hospital room while our mothers cried. I didn’t know death. I barely knew sickness. And Connor was so unafraid. I couldn’t conceptualize that a child, who was like me in every way, was going to die, so I did what I knew: I played with my friend.

His parents and the rest of our community prayed for him to be healed, for his small body to fight against itself. Despite our desperation, there came a time when Connor’s family knew that he wouldn’t have the opportunity to grow up.

My grief for him was as small as I was. It grazed me, but it didn’t incapacitate me. However, it changed the course of my life, laying the groundwork for a shadow of loss that would never leave my side, even if I didn’t know it yet.

I think of Connor often. His eight-year-old self is tucked into my brain, immortalized alongside the girl that I was when I knew him. She was restless and voracious. She swatted at bees and didn’t know how to sit still. I had just started processing his death when another blow struck.

My grandfather died when I was 11. He was the only grandfather I knew, and I looked forward to the days that my family piled into the car to drive to my mom’s childhood home in Hurst, Texas. Pa would wait for us at the door, bending his already-hunched back to embrace us.

He taught me Chinese checkers and Chicken Foot. He built backyard games out of pipes and tennis balls. He picked pecans off of the neighborhood trees so my grandmother could bake pies. Pa worked hard and stayed quiet, and like a gentle giant, had an air of kindness that made me feel protected.

His death was expected for his age but sudden for our family — a heart attack. Instead of driving to his home, we drove to the hospital that he would die in, squeezing into the small room to be with him. We tried to comfort him while he laid in pain and disarray.

He had a moment of clarity before he passed, as if coming out of a dream. I could see him taking us in one by one, lined against the wall because there weren’t enough chairs to hold us. Our silence was too loud; he had to speak, and this is what he said: “It’s like you’re all waiting for me to die.” He was right, and there was nothing we could do to stop it.

Remembering Pa reminds me that I was once a little girl with a bigger family. He reminds me that my mom, too, was a little girl. My dad, though he never knew his dad, had a father figure that played dominoes with him and sold him a truck.

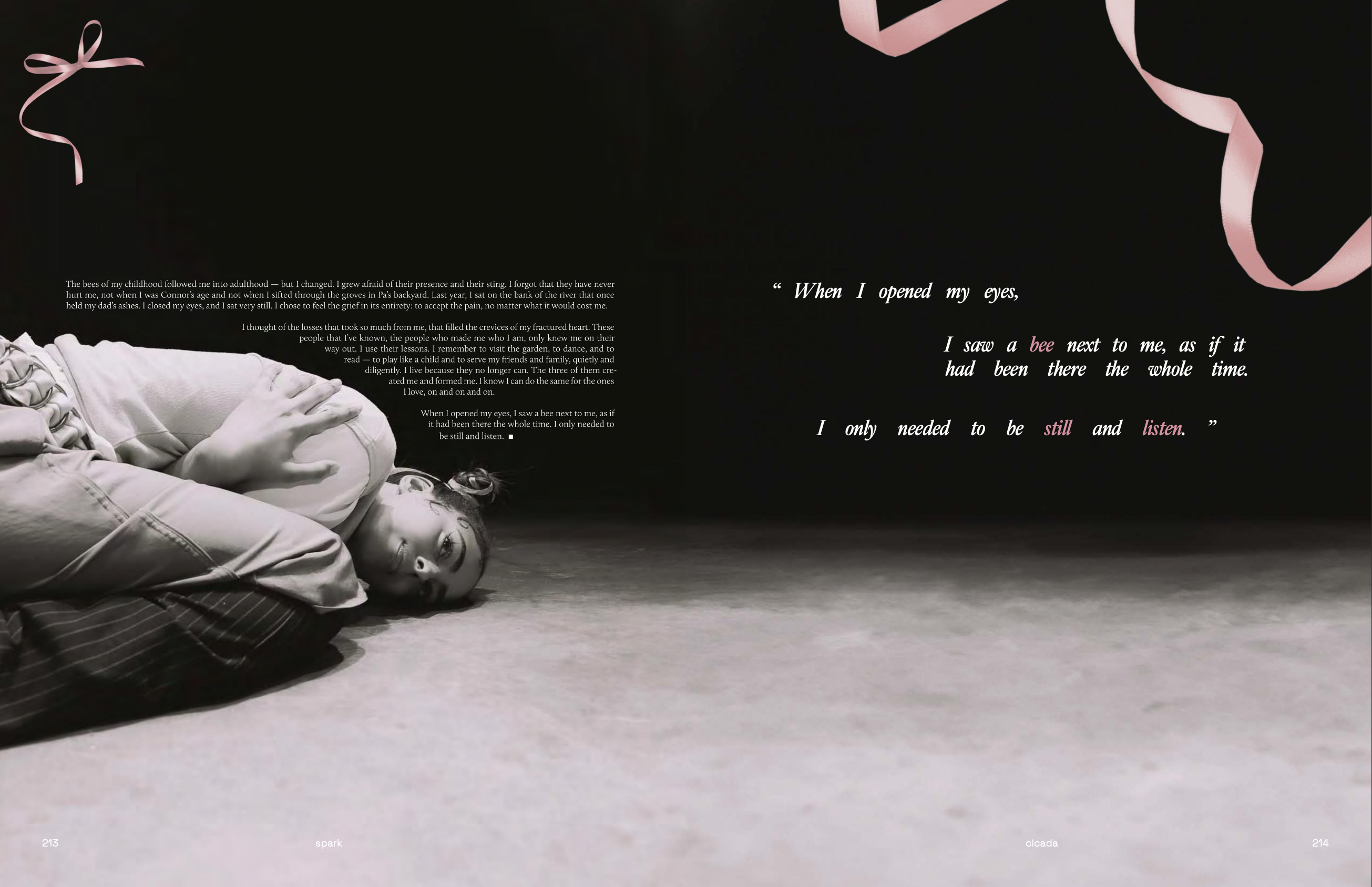

The bees of my childhood followed me into adulthood — but I changed. I grew afraid of their presence and their sting. I forgot that they have never hurt me, not when I was Connor’s age and not when I sifted through the groves in Pa’s backyard. Last year, I sat on the bank of the river that once held my dad’s ashes. I closed my eyes, and I sat very still. I chose to feel the grief in its entirety, to accept the pain, no matter what it would cost me.

I thought of the losses that took so much from me, that filled the crevices of my fractured heart. These people that I've known, the people who made me who I am, only knew me on their way out. I use their lessons. I remember to visit the garden, to dance, and to read — to play like a child and to serve my friends and family, quietly and diligently. I live because they no longer can. The three of them created me and formed me. I know I can do the same for the ones I love, on and on and on.

When I opened my eyes, I saw a bee next to me, as if it had been there the whole time. I only needed to be still and listen. ■

Layout: Cara Ung

Photographer: Amy Lee

Stylists: Gabriela Fuentes & Fernanda Lopez

Set Stylist: Floriana Hool

HMUA: Lily Cartagena

Models: Arliz Muñoz & Melat Woldu

Other Stories in Cicada

© 2025 SPARK. All Rights Reserved.