In Search of the Perpetual Self

By Hayle Chen

May 2, 2023

What is forgotten can be rebirthed.

When I arrive home in Combray that winter, my mother offers me the warmth of my childhood home, petites madeleines, and a cup of tea, which at first, I refuse at first. There’s a weariness set down to the marrow of my bones, a dread that I cannot seem to shake about the promised monotony each new day holds. I ladle a spoonful of tea and break off a morsel of the cake to place in the liquid. I lift the spoon to my lips, and no sooner had the warm liquid, and the crumbs with it, touched my palate… An exquisite pleasure had invaded my senses, but individual, detached, with no suggestion of its origin. Joy erupts in my soul; mortality no longer befits me, I am interminable. How do I generate it again? I assemble the concoction once more, bringing the spoon to my lips once, twice, thrice. It is in vain. The moment is gone.

For Marcel Proust, dipping a madeleine in tea catalyzed his discovery of involuntary autobiographical memory — a phenomenon that, because of his vivid documentation, is charmingly referred to as a “Proustian moment.” To experience this moment is to have a memory triggered by means of olfaction or gustation, suddenly and unwittingly.

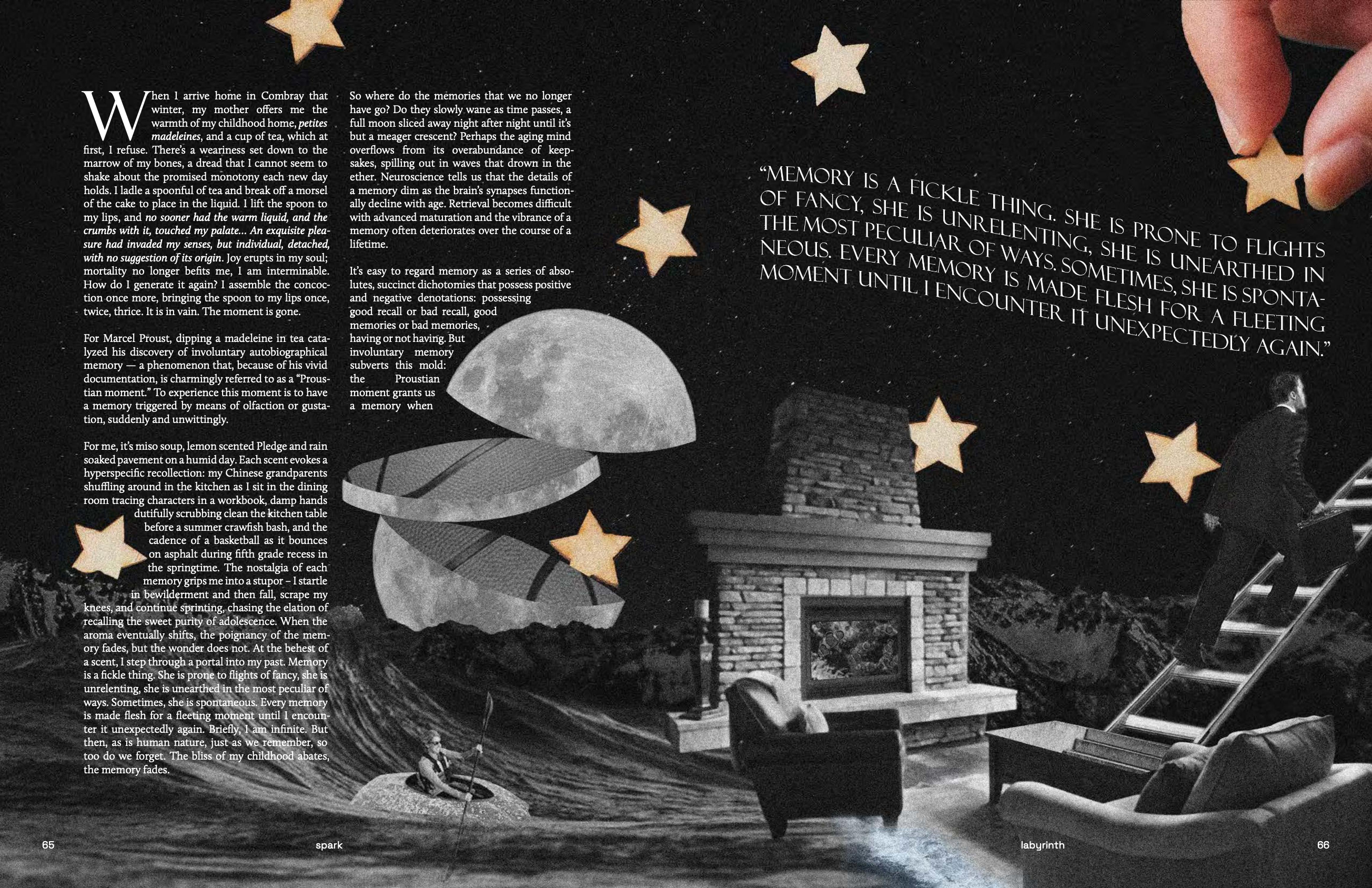

For me, it’s miso soup, lemon scented Pledge and rain soaked pavement on a humid day. Each scent evokes a hyperspecific recollection: my Chinese grandparents shuffling around in the kitchen as I sit in the dining room tracing characters in a workbook, damp hands dutifully scrubbing clean the kitchen table before a summer crawfish bash, and the cadence of a basketball as it bounces on asphalt during fifth grade recess in the springtime. The nostalgia of each memory grips me into a stupor – I startle in bewilderment and then fall, scrape my knees, and continue sprinting, chasing the elation of recalling the sweet purity of adolescence. When the aroma eventually shifts, the poignancy of the memory fades, but the wonder does not. At the behest of a scent, I step through a portal into my past. Memory is a fickle thing. She is prone to flights of fancy, she is unrelenting, she is unearthed in the most peculiar of ways. Sometimes, she is spontaneous. Every memory is made flesh for a fleeting moment until I encounter it unexpectedly again. Briefly, I am infinite. But then, as is human nature, just as we remember, so too do we forget. The bliss of my childhood abates, the memory fades.

So where do the memories that we no longer have go? Do they slowly wane as time passes, a full moon sliced away night after night until it’s but a meager crescent? Perhaps the aging mind overflows from its overabundance of keepsakes, spilling out in waves that drown in the ether. Neuroscience tells us that the details of a memory dim as the brain’s synapses functionally decline with age. Retrieval becomes difficult with advanced maturation and the vibrance of a memory often deteriorates over the course of a lifetime.

![]()

It’s easy to regard memory as a series of absolutes, succinct dichotomies that possess positive and negative denotations: possessing good recall or bad recall, good memories or bad memories, having or not having. But involuntary memory subverts this mold: the Proustian moment grants us a memory when we are not actively searching for it. Triggered by external sensory experiences, these memories are thought as the body’s nature’s compensation for the decline in voluntary and strategic retrieval that accompanies aging.

To experience and to forget is the fate of man. So what does it mean that what is lost can still be found, even when we don’t know we lost something in the first place? A taste, a smell, a touch, a view, and a sound – they can catalyze a memory, invoking the past and thrusting a forgotten moment into the present. We are a homemaker’s antique hutch, filled to the brim with knick-knacks and valuables; we are a gardener’s bucket with a hairline fracture, slowly losing our stale, tepid water as time passes by.

We have a human tendency to want to endure, to have a life well-lived if only so others will remember us, lest we be omitted from history entirely. We labor in hope of being memorialized, but we rarely consider what memories lie dormant within ourselves. It matters as much that we remember who we are as it does that others remember us. While Proust remembered various moments during his childhood in Illiers-Combray the moment the pastry touched his palate, when a beam of sunlight shutters into a dark room exactly right amid the smell of colored pencils and permanent markers, I’m transported back to afternoons sitting on the living room carpet at my cousin’s house, folding paper airplanes in preparation for a flying contest. Each specific appeal to my senses — only emerging in perfect, unreplicable conditions — evokes a moment lost in time profoundly outside my current temporality. My past self lives on in the present, my present self pulls forth the past.

![]()

We often think what is forgotten is forever lost, but in the spaces we inhabit, the people we touch, and the feelings we have, we leave remnants of ourselves – and we keep some as well.

A Proustian moment is a gift, an offering at the altar that is our mind, presented by our childhood selves. Memories are prioritized, filed and stored and retrieved when necessity dictates that remembering a certain action, event, or experience would aid in survival. Our mind delineates: short-term, long-term, suppressed. But what is forgotten can be rebirthed. We can recover a poignant memory because, in essence, it is never truly lost. The senses transcend ephemerality; the mind is elastic. I am not mediocre, accidental, or mortal. Layers upon layers of myself exist, are hidden and may be unearthed and cherished as long as they last.

Perpetuity exists. She is inaccessible, she is elusive, she does not heed the commands of Routine and Structure. She exists; she lives in the self.

Rich miso, the sharp citrus of Pledge, a sidewalk drenched after a thunderstorm. My childhood comes flooding back. ■

Layout: Samantha Firmin

When I arrive home in Combray that winter, my mother offers me the warmth of my childhood home, petites madeleines, and a cup of tea, which at first, I refuse at first. There’s a weariness set down to the marrow of my bones, a dread that I cannot seem to shake about the promised monotony each new day holds. I ladle a spoonful of tea and break off a morsel of the cake to place in the liquid. I lift the spoon to my lips, and no sooner had the warm liquid, and the crumbs with it, touched my palate… An exquisite pleasure had invaded my senses, but individual, detached, with no suggestion of its origin. Joy erupts in my soul; mortality no longer befits me, I am interminable. How do I generate it again? I assemble the concoction once more, bringing the spoon to my lips once, twice, thrice. It is in vain. The moment is gone.

For Marcel Proust, dipping a madeleine in tea catalyzed his discovery of involuntary autobiographical memory — a phenomenon that, because of his vivid documentation, is charmingly referred to as a “Proustian moment.” To experience this moment is to have a memory triggered by means of olfaction or gustation, suddenly and unwittingly.

For me, it’s miso soup, lemon scented Pledge and rain soaked pavement on a humid day. Each scent evokes a hyperspecific recollection: my Chinese grandparents shuffling around in the kitchen as I sit in the dining room tracing characters in a workbook, damp hands dutifully scrubbing clean the kitchen table before a summer crawfish bash, and the cadence of a basketball as it bounces on asphalt during fifth grade recess in the springtime. The nostalgia of each memory grips me into a stupor – I startle in bewilderment and then fall, scrape my knees, and continue sprinting, chasing the elation of recalling the sweet purity of adolescence. When the aroma eventually shifts, the poignancy of the memory fades, but the wonder does not. At the behest of a scent, I step through a portal into my past. Memory is a fickle thing. She is prone to flights of fancy, she is unrelenting, she is unearthed in the most peculiar of ways. Sometimes, she is spontaneous. Every memory is made flesh for a fleeting moment until I encounter it unexpectedly again. Briefly, I am infinite. But then, as is human nature, just as we remember, so too do we forget. The bliss of my childhood abates, the memory fades.

So where do the memories that we no longer have go? Do they slowly wane as time passes, a full moon sliced away night after night until it’s but a meager crescent? Perhaps the aging mind overflows from its overabundance of keepsakes, spilling out in waves that drown in the ether. Neuroscience tells us that the details of a memory dim as the brain’s synapses functionally decline with age. Retrieval becomes difficult with advanced maturation and the vibrance of a memory often deteriorates over the course of a lifetime.

It’s easy to regard memory as a series of absolutes, succinct dichotomies that possess positive and negative denotations: possessing good recall or bad recall, good memories or bad memories, having or not having. But involuntary memory subverts this mold: the Proustian moment grants us a memory when we are not actively searching for it. Triggered by external sensory experiences, these memories are thought as the body’s nature’s compensation for the decline in voluntary and strategic retrieval that accompanies aging.

To experience and to forget is the fate of man. So what does it mean that what is lost can still be found, even when we don’t know we lost something in the first place? A taste, a smell, a touch, a view, and a sound – they can catalyze a memory, invoking the past and thrusting a forgotten moment into the present. We are a homemaker’s antique hutch, filled to the brim with knick-knacks and valuables; we are a gardener’s bucket with a hairline fracture, slowly losing our stale, tepid water as time passes by.

We have a human tendency to want to endure, to have a life well-lived if only so others will remember us, lest we be omitted from history entirely. We labor in hope of being memorialized, but we rarely consider what memories lie dormant within ourselves. It matters as much that we remember who we are as it does that others remember us. While Proust remembered various moments during his childhood in Illiers-Combray the moment the pastry touched his palate, when a beam of sunlight shutters into a dark room exactly right amid the smell of colored pencils and permanent markers, I’m transported back to afternoons sitting on the living room carpet at my cousin’s house, folding paper airplanes in preparation for a flying contest. Each specific appeal to my senses — only emerging in perfect, unreplicable conditions — evokes a moment lost in time profoundly outside my current temporality. My past self lives on in the present, my present self pulls forth the past.

We often think what is forgotten is forever lost, but in the spaces we inhabit, the people we touch, and the feelings we have, we leave remnants of ourselves – and we keep some as well.

A Proustian moment is a gift, an offering at the altar that is our mind, presented by our childhood selves. Memories are prioritized, filed and stored and retrieved when necessity dictates that remembering a certain action, event, or experience would aid in survival. Our mind delineates: short-term, long-term, suppressed. But what is forgotten can be rebirthed. We can recover a poignant memory because, in essence, it is never truly lost. The senses transcend ephemerality; the mind is elastic. I am not mediocre, accidental, or mortal. Layers upon layers of myself exist, are hidden and may be unearthed and cherished as long as they last.

Perpetuity exists. She is inaccessible, she is elusive, she does not heed the commands of Routine and Structure. She exists; she lives in the self.

Rich miso, the sharp citrus of Pledge, a sidewalk drenched after a thunderstorm. My childhood comes flooding back. ■

Layout: Samantha Firmin

Other Stories in Labyrinth

© 2025 SPARK. All Rights Reserved.