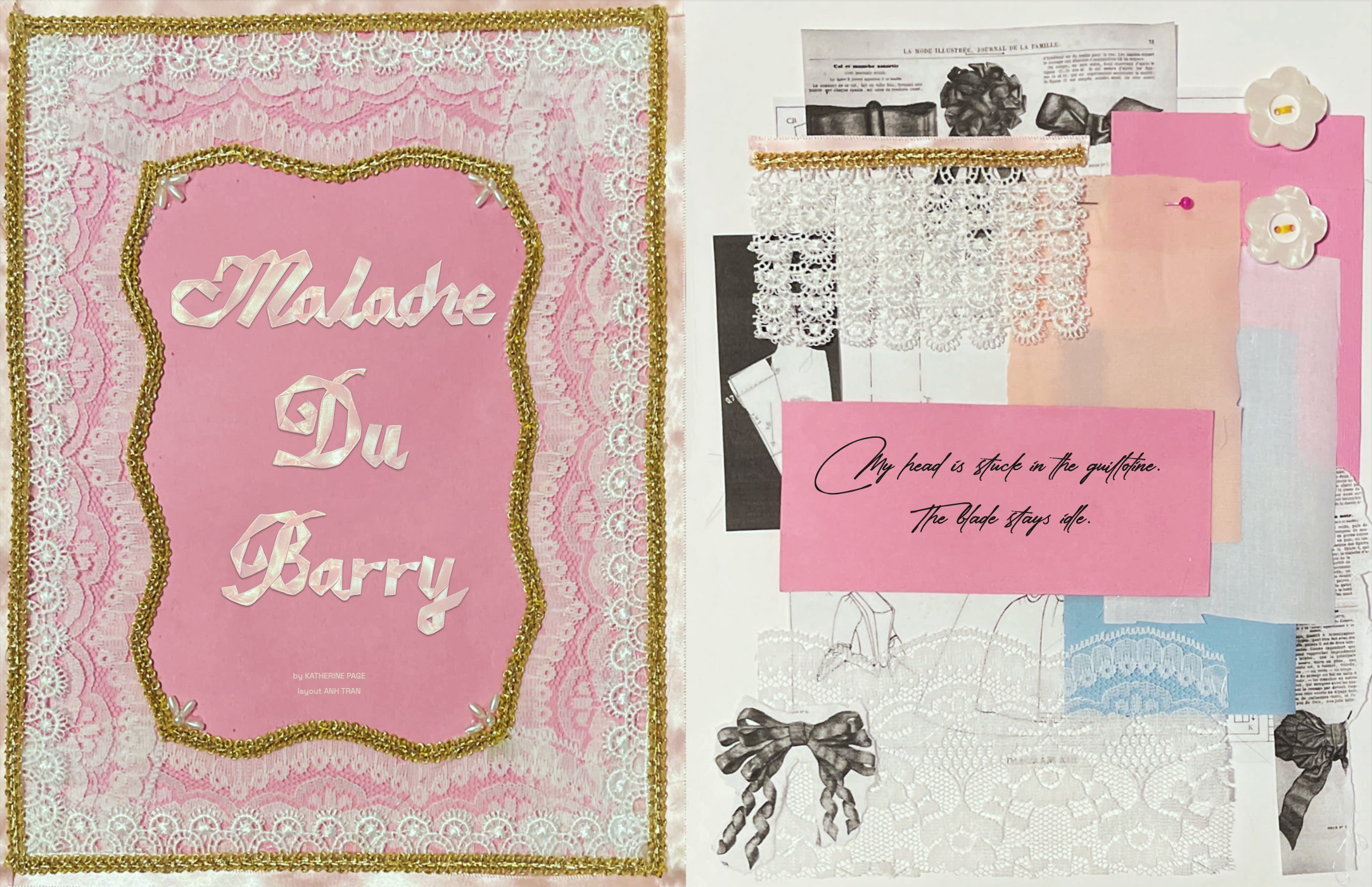

MALADIE DU BARRY

By Katherine Page

April 27, 2024

My head is stuck in the guillotine. The blade stays idle.

Something still new to me is smooth walls. I spent most of my life with textured walls: a cheaper and faster option that covered imperfection with imperfections. Bumps stuck out awkwardly and sharply, their disfigurement demanding attention. This made it hard to put up any decor — posters ripped or looked wonky. Putty would not stick, and if it did, it took the paint off with it. When I arrived at my college dorm, my luxurious paradise, I packed posters and postcards onto the shiny refined walls. I curated honeycombs of art for the smooth surfaces. When I wake up in the morning and see my crafted mural, I find myself smiling with accomplishment.

I handpicked art with Greco-Roman and European influences: the academia aesthetic, Rococo, Renaissance, Art Nouveau, Monet, De Goya, Gabrielle d'Estrées et une de ses soeurs, Mucha, Bieres de la Meuse. But one postcard in particular always sticks out to me. She sits right above my desk — Jeanne du Barry.

Big white-gray hair falls in graceful ringlets around her neck. Feathers and flowers adorn the crown of her head. She flaunts her perfectly white decolletage and pink rosy cheeks. Her lips are pursed into a sweet smile, and her sparkling green eyes stare at me now.

I find myself looking back.

When I was a kid, my mother owned a sewing business. She was a seamstress, and as her daughter, I was expected to help. I’d measure out the fabrics, fetch her pincushion, and hold folds and ruffles in place while she pinned them down. It wasn’t lucrative, but it was fun — fun in the way that childlike eyes frame everything serendipitously. In reality, I helped because if I didn’t, she couldn’t have sewn enough pieces in time. And that meant later I would see her crying over the little white envelopes that doomed us to smaller meals.

I imagine Jeanne du Barry had a childhood similar to mine because her mother was a seamstress too. I imagine that she knew the feeling of pricking her thumbs on sewing pins and getting scolded for the little trace of blood she left on the fabric. I imagine her trying to fit a thimble on her thumb and getting dismayed the same way I did when she realized her hands were much too small. I imagine her wrapping herself in bundles of pretty fabric, pretending to be someone much more than she was, the same way that I did.

Everyone I’ve become friends with at school has lived with some kind of exorbitant opulence. When I venture out of my dormitory, I am assaulted by their stories of grandeur — Paris, Germany, Romania. I hear about their countless ski trips, the amount they spend on groceries, the small luxuries they get to experience day to day. Madame du Barry accompanies me as I hear about these things, and she sees the way I can do nothing but listen. The stories bounce around my head at night, tinged with jealousy as I wish that I was raised in a better environment.

I watch her as she does the same. The moment she manages to step foot into the Court of Versailles, taken in by the King as his maîtresse-en-titre, she hears the nobility buzzing on and on about hunting trips, lush pastries, and grand carriages carrying them through the palace garden. She is silent — not allowed to speak in court because of her lack of status. We are both forced into silence because of the predicaments of our shameful childhoods, and we must listen to people vaunt about lives that we try to live every day. Despite this, we try.

Madame du Barry spends her days trying on new gowns and jewelry. She spends her mornings painting a thoughtfully curated picture. Servants tie her into her corsets and petticoats. They style her hair and makeup as she frets and fusses about every tiny detail. That strand is out of place. This blush is the wrong shade. She adorns her hands and wrists and neck and hair with glittering bijouteries.

I’m stuck in a similar lifestyle. I spend my time buying new shoes and sweaters, online shopping, and scrolling through Pinterest, curating every aspect of myself that I can. I meticulously curl my bangs, punctiliously sketch my eyeliner, and scrupulously pick an outfit. Like du Barry, I agonize and anguish about every detail of myself. My shirt is the wrong shade of white. My hair is uneven and stupid-looking. As I leave my dorm, I am shaken by my fear of looking sloppy. Not in the sense that I look messy and unkempt, but in the sense that the cheapest option is always the ugliest. Can they tell that my shirt is name-brand, that my shoes are $150? Or do they see through my performance? Do they perceive me as I was only a couple of years ago, re-wearing the same five pants and shirts and smearing my face with the cheapest makeup available?

Madame du Barry stands inches away from a mirror, fixing her makeup. I am standing behind her, waiting to do the same.

I don’t need to worry about money now, but I still do — it’s the consequences of my own actions. Trying desperately to emulate the more moneyed people around you means spending a lot of money yourself. Clothes, shoes, jewelry, perfume, makeup, decor — these all add up. I can afford them all now, but the money I have left over for things like rent and tuition dwindles as I fight my most shameful desires. I confide this to the Comtesse and she stays smiling sweetly at me. She spent most of her life drowning in debt. She amassed her arrears from her time in Versailles, spending and spending and spending. Du Barry had a large monthly allowance from the King, but still, she spent money she didn’t have on superfluous things up until her death.

If I close my eyes, I can see it: the guillotine, the angry crowd cheering as the executioner drags Jeanne out of the tumbrel. She screams and begs for her life. «Tu vas me faire du mal! Pourquoi?» She had been denounced by the Jacobins, accused of using her money to help the wealthy flee from the French Revolution. When she was caught, she begged for her life, offering precious gems and jewels she had hidden in exchange. Still, the Jacobins dragged her to the guillotine, intent on killing her for her life amongst the nobility.

Is this a warning? Is this what lies ahead of me? Her story feels too uncanny, as if someone was trying to tell me I would end up like her, ostracized from those I try to be and rejected by the people I knew in the past. Will my financial irresponsibilities swell, balloon, distend until they blow up in my face? Will it get to a point of no return? Will I face my own metaphorical chopping block, put right back where I started, or worse? Jeanne du Barry was never able to overcome her own cardinal impulses. Will I?

I see the way Jeanne struggles and writhes against the men who firmly lead her to her fate. She screams and yells. Her head is placed inside the lunette. «De grâce, monsieur le bourreau, encore un petit moment!»

Her lack of ignominy is jarring. She begs and pleads for her life, denying her guilt, absolving herself from blame. She tries to save herself by throwing more money at the problem. Jeanne du Barry is tone-deaf and consumed by greed and decadence, but I feel shame deeply in my bones. It radiates off me like a bad smell, and I can taste it like bile in the back of my throat. The thing I am embarrassed of most is my childhood, and everything I do, everything I buy, is to escape my history. My spending habits come from shame, and now they are my shame. But Jeanne du Barry was gluttonous and proud and corrupted by her lifestyle. Unlike me, she was never ashamed.

The blade falls, and her head comes rolling onto the wooden platform. Her white curls swiveling and twisting with it. It stops right at the edge, right in front of me. Her green eyes stare blankly at nothing. I am nothing but a face in the crowd.

In my dorm, I notice a blank spot where Madame du Barry’s postcard once was. I look behind my desk to find her fallen between the baseboard and the wall. I return to my mirror, alone. Inches away from it, I continue to do my makeup. ■

Layout: Anh Tran

Other Stories in RAW

© 2025 SPARK. All Rights Reserved.