My Naked Body Means Nothing

April 19, 2023

Graphic by Lucy Leydon

“Your body is a temple.”

This meaningless phrase carries no weight to me now, but in my early childhood, I felt forced to live by it. I believed in it so heavily. The idea that my body is sacred was repeated so often I had no room to forget it.

I felt I could not touch my naked body, or even look at it.

I covered mirrors while I dressed myself, turned away from my reflection in the shower head, and startled myself everytime I accidentally grazed my fingers over my exposed skin. I was not allowed to observe my naked body, or sit with it. I was not allowed to disfigure the bareness of my body that was meant for something else, something greater than myself. I had to treat it as if it were delicate glass, a porcelain doll used strictly for display. I had to save my nakedness for something. I didn’t know what for. Was it for a partner? Was it for God? Was it for death? The soil in the ground was the only thing allowed to hug me, engulf me, touch me without startling the ever so “delicate” skin.

I felt detached from my nakedness. It was an entity outside of myself that I was caring for. My nakedness was a mannequin I was forced to care for before her display. A mannequin I had to carry everywhere with me, one I had to meticulously dress and screw flailing limbs back together that wouldn’t stay put. Patiently waiting as I looked after her. I grew tired of waiting for an imminent performance that never came.

It wasn't until I roamed around the surreal art exhibit inside the Menil in Houston, Texas, that I realized what nakedness meant.

This meaningless phrase carries no weight to me now, but in my early childhood, I felt forced to live by it. I believed in it so heavily. The idea that my body is sacred was repeated so often I had no room to forget it.

I felt I could not touch my naked body, or even look at it.

I covered mirrors while I dressed myself, turned away from my reflection in the shower head, and startled myself everytime I accidentally grazed my fingers over my exposed skin. I was not allowed to observe my naked body, or sit with it. I was not allowed to disfigure the bareness of my body that was meant for something else, something greater than myself. I had to treat it as if it were delicate glass, a porcelain doll used strictly for display. I had to save my nakedness for something. I didn’t know what for. Was it for a partner? Was it for God? Was it for death? The soil in the ground was the only thing allowed to hug me, engulf me, touch me without startling the ever so “delicate” skin.

I felt detached from my nakedness. It was an entity outside of myself that I was caring for. My nakedness was a mannequin I was forced to care for before her display. A mannequin I had to carry everywhere with me, one I had to meticulously dress and screw flailing limbs back together that wouldn’t stay put. Patiently waiting as I looked after her. I grew tired of waiting for an imminent performance that never came.

It wasn't until I roamed around the surreal art exhibit inside the Menil in Houston, Texas, that I realized what nakedness meant.

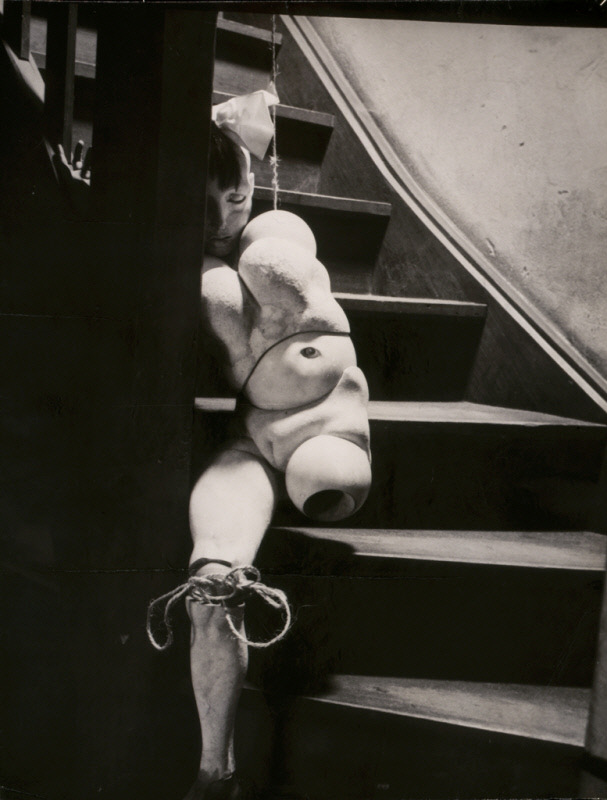

Image via the Menil Collection

I stumbled upon Hans Bellmer’s photograph from 1935, “The Doll,” also named “La Poupée.”

A monochromatic, contorted mannequin. Her upside-down torso clings to her upright head, desperate to stay intact. Ropes affix themselves to the bottom of her leg. She is missing a leg and an arm while a hand rests on the stair railing. Seeing her naked body parts in a disorganized manner detached them from their sanctity. Her body parts were no longer a part of a cohesive being — they were pieces of disorder and chaos. Holiness, fragility, and grace no longer defined the temple of nakedness.

A monochromatic, contorted mannequin. Her upside-down torso clings to her upright head, desperate to stay intact. Ropes affix themselves to the bottom of her leg. She is missing a leg and an arm while a hand rests on the stair railing. Seeing her naked body parts in a disorganized manner detached them from their sanctity. Her body parts were no longer a part of a cohesive being — they were pieces of disorder and chaos. Holiness, fragility, and grace no longer defined the temple of nakedness.

In a sudden moment, I remembered seeing this doll. I recognized her. She looked like my reflection from the glossy eyes of the mannequin I was forced to care for. A torn-apart version of myself. Seeing her body parts in unexpected places gave them more meaning. One would think detaching them from their usual place would detach them from their purpose and make them futile. To me, it gave them a greater meaning — the greatest meaning is none at all. When I was a young girl, I never thought of my body as something more than what it was: a vessel to carry my blood and organs. I used my body for many things: to sit on the kitchen floor as my mother cooked, to dance to songs I heard on TV, to run around my neighborhood and watch the sky without looking at what was in front of me. When I dressed myself, I never closed my eyes or turned away from mirrors. I was too busy thinking of the sky and what it would look like as I chased it. There was not a heavy mannequin in front of me waiting to be cared for. I was free, curious, and had no meaning at all but to live.

Hans Bellmer’s art piece embodied the little girl I was, and art as a whole. Neither have any greater purpose than to live in this world. People choose to observe it, interpret it, study it, and dissect it. However, art is inherently made to live. It is created for the sole purpose of being created.

Nakedness, at its core, is an art form.

I have lived my adult life with the idea that my bareness is meant for a greater purpose. That I am an art piece waiting to be studied and dissected.

I believed nakedness was a state of being, a performance, a container left to fill and showcase.

My nudity is not important. It is not meant for sexual purposes, for divinity, or for science. I am not a creature that lives life for the purpose of a temporary meaning; my nakedness has no greater purpose. There is no performance I need to prepare for or an exhibition that is waiting for me. I am not a creature meant for taxidermy, to be displayed and analyzed.

By seeing nakedness in such a startling, detached setting, to see bare body parts in distorted order, I began to understand the importance, or rather the unimportance, of my nakedness.

My naked body means nothing. ■

Hans Bellmer’s art piece embodied the little girl I was, and art as a whole. Neither have any greater purpose than to live in this world. People choose to observe it, interpret it, study it, and dissect it. However, art is inherently made to live. It is created for the sole purpose of being created.

Nakedness, at its core, is an art form.

I have lived my adult life with the idea that my bareness is meant for a greater purpose. That I am an art piece waiting to be studied and dissected.

I believed nakedness was a state of being, a performance, a container left to fill and showcase.

My nudity is not important. It is not meant for sexual purposes, for divinity, or for science. I am not a creature that lives life for the purpose of a temporary meaning; my nakedness has no greater purpose. There is no performance I need to prepare for or an exhibition that is waiting for me. I am not a creature meant for taxidermy, to be displayed and analyzed.

By seeing nakedness in such a startling, detached setting, to see bare body parts in distorted order, I began to understand the importance, or rather the unimportance, of my nakedness.

My naked body means nothing. ■

Other Stories in Life

© 2025 SPARK. All Rights Reserved.