My body is a mobile home.

By Andreana Joi Faucette

May 3, 2025

I begin to feel unwell.

For brief moments in the past, I thought I could move my body with my mind.

In childhood, I could never figure out where my body would go when I died. I tried conducting field research — the daydreams — but was always too frightened by the other side to confront it.

At age 12, I found myself plagued by immersive daydreams. I’d close my eyes and open them to find my body had been transplanted with surgical precision out of reality and into fatality. My home became a beast awakened — with tectonic-plate-teeth made of fiberglass foundations shifting to squish my windpipe, hungry for a meal of one.

I could never scream in the daydreams — only stand and stare at my fate. The arrhythmic beating in my chest would crescendo until I could perfectly time shutting my eyes against death with a painless passing.

Eventually, I’d die.

I’d resurrect myself moments later, feeling somewhat relieved — alive.

—

At the funeral of my estranged grandmother, I find myself unable to parse out the features on her face which might have resembled mine.

The mortician has buried her in her Sunday best — a matching skirt and jacket set in springtime colors, even though it's February. Both are ill-fitting, the colors awkward and linens rigormortic. Neither distract from the morbidity of the affair. In my daydreams, death was swift and avoidable, compounding in fatalistic moments and cataclysmic blasts. Here, it is unceremonious and awkward, hidden under mortuary makeup.

When it is my chance to mourn the deceased, I stall in front of her casket. Despite holding back the procession of weepy relatives, I’m tempted to whisper her name — to test if this body, all gray and severe — is the same one I knew. I bow my head in pretend prayer instead, shutting my eyes tightly enough to shield me from the knowledge that my body will also expire some day.

Later, my father calls and reminds me to tell the eye doctor to check for glaucoma; it’s in your family history.

I concede to my dad’s wishes, remembering how he’d procrastinate his doctor’s appointments. He’s just visited the eye doctor for the first time in years, but he’s getting old now. I wonder if he feels it, too — time catching up to him, the desire to shut your eyes against fatality.

I don’t tell my father that my time is already monopolized by therapists and specialists; professors and nutritionists. I don’t mention my prescribed cocktail of psychotropic medications given to return me to a physical and emotional baseline that I’m unsure I’ve ever experienced.

I only nod politely at him, and stand, staring at my fate.

–

In my therapist’s virtual waiting room, I await an email containing her latest list of insurance-approved nutritionists. I know I’m too afraid to open it — to confront the dirty work of self-improvement.The list will sit, unopened, in my inbox for weeks, before going stale like the bread I never bothered to turn into sandwiches.

Like a metastasizing illness, fear goes for my vital organs first.

It starts in my mouth. I barely eat, wasting money on coffees and club covers while I avoid the stagnation of sitting with myself. I chase my meds with gulps of water as religiously as I can. Since I’m an atheist, I forget some mornings and double-dose myself at night. I fortify my body’s crumbling cell walls with multivitamins and hope they do not crumble.

I lose myself in novels of waifish women who forget to eat breakfast, convinced I’ll become more like them. At midnight, I sit awake and shove calorie-dense, pre-packaged brownies between my teeth.

I can barely feel my fingertips, so I close my eyes and imagine strolling down grocery aisles for meals to fill this home with.

In my notes app, I begin a running tally of what I’d like to prepare. They’re great feasts: chickpeas, feta, sun-dried tomatoes, Hot Cheetos with cream cheese. Sometimes, I cave — drive the ten minutes to go to the grocery store and fill my cart with a hundred dollars of foodstuffs. I eat half in one sitting and swear myself to abstinence the next day.

Luckily, I have been taught how to take care of myself.

When I feel this way, I know to drive 15 minutes to the nail salon in the strip mall behind my primary school. There, I can forget that self-care is little more than skin deep.

Suzanne — the manicurist I’ve been loyal to since my high school prom — holds a novelty timer shaped like an egg. She hums gleefully and winds its little red dial up.

“The basic pedicure comes with a 10-minute massage,” she tells me, then cranks the dial five notches further, “But for you — 15.”

She winks.

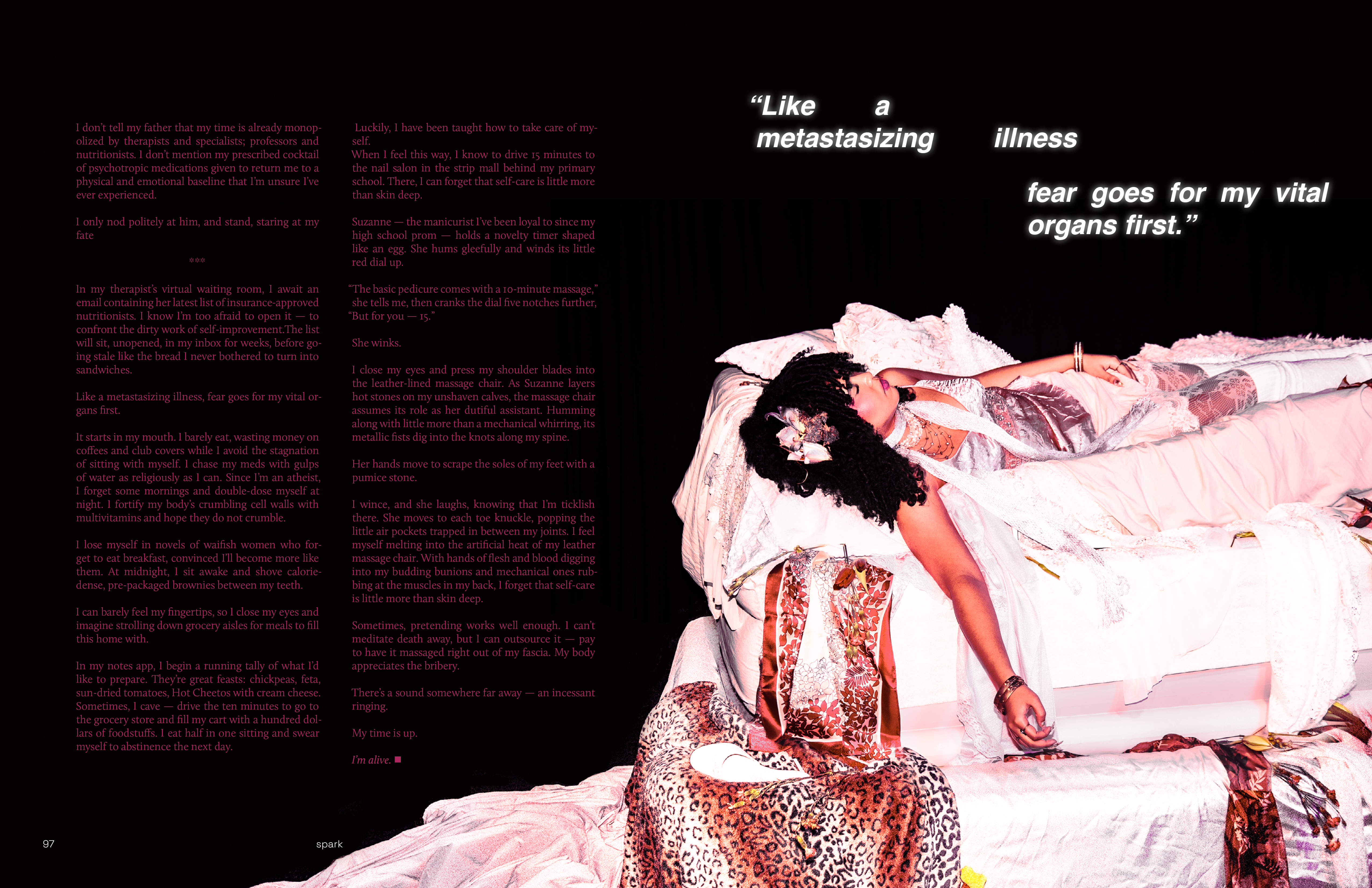

I close my eyes and press my shoulder blades into the leather-lined massage chair. As Suzanne layers hot stones on my unshaven calves, the massage chair assumes its role as her dutiful assistant. Humming along with little more than a mechanical whirring, its metallic fists dig into the knots along my spine.

Her hands move to scrape the soles of my feet with a pumice stone.

I wince, and she laughs, knowing that I’m ticklish there. She moves to each toe knuckle, popping the little air pockets trapped in between my joints. I feel myself melting into the artificial heat of my leather massage chair. With hands of flesh and blood digging into my budding bunions and mechanical ones rubbing at the muscles in my back, I forget that self-care is little more than skin deep.

Sometimes, pretending works well enough. I can’t meditate death away, but I can outsource it — pay to have it massaged right out of my fascia. My body appreciates the bribery.

There’s a sound somewhere far away — an incessant ringing.

My time is up.

I’m alive. ■

Layout: Emmy Chen

Photographer: Sharanya Gupta

Videographer: Rylie Shieh

Stylists: Madison Morante & Zoe Costanza

HMUA: Jaishri Ramesh & Rachel Zhou

Nail Artist: Anoushka Sharma

Model: Genesis Pieri

Other Stories in Corpora

© 2025 SPARK. All Rights Reserved.