Naïve Physics

By Ella Rous

December 8, 2024

| Avoiding one another has become something akin to a love language or an intuition. Can we overcome the science of missed connections? |

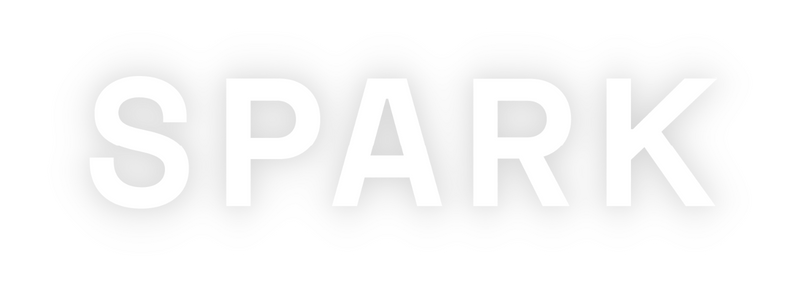

Crossing the street onto campus, watch yourself from above. You hesitate, bob, and weave. You make unwanted eye contact, eyes flickering away deferentially, and make the slightest adjustments to your footfalls to avoid the paths of others. With your phone out and open to Google Calendar, iMessage, or Instagram, you might just barely avoid walking straight into a tree or a rack of bikes. (Hey, it happens.)

Picture a waterslide. It loop-de-loops, arcing into the sky, and curves back down to track a path parallel to the ground before shooting its gleeful rider into the pool at its base.

What path does the rider take? Do they fly up into the sky, completing a sky-writer’s perfect “o”? Or do they go forward, then down?

Naïve physics is a kind of common knowledge: things come down after they go up and a ball can’t go through the fence unless one or the other isn’t a solid object. We use it every day of our lives. It’s how we make trajectory adjustments. It’s why we don’t go around bumping into one another and falling to the ground any time we enter another’s vicinity.

Recently, I’ve been hesitating on Speedway, waiting for a biker or a couple clutching hands to make the decision: around? in which direction? stop, go?

Who’s gonna swerve: you or me?

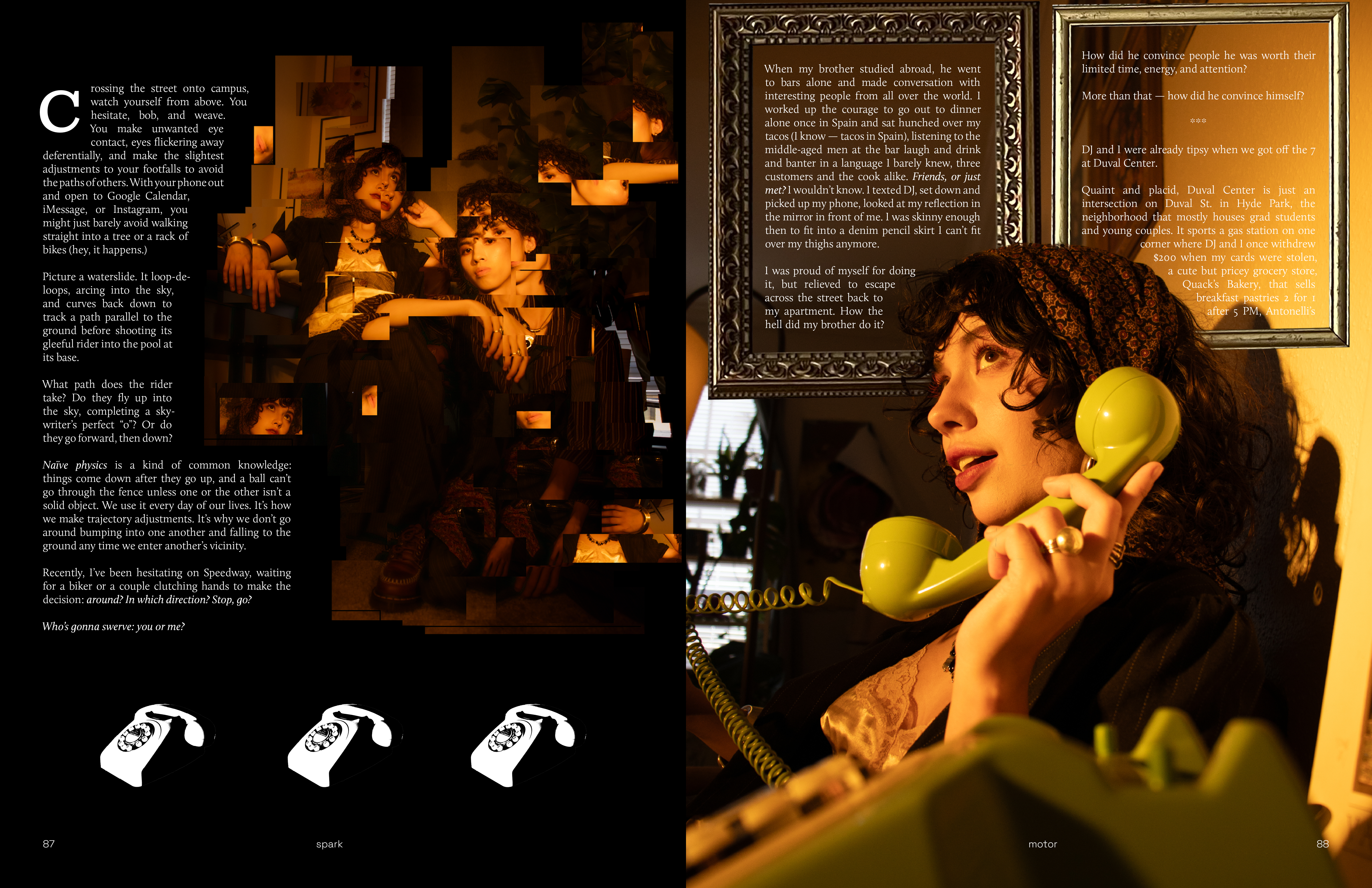

When my brother studied abroad, he went to bars alone and made conversation with interesting people from all over the world. I worked up the courage to go out to dinner once alone in Spain and sat hunched over my tacos (I know — tacos in Spain), listening to the middle-aged men at the bar laugh and drink and banter in a language I barely knew, three customers and the cook alike. Friends, or just met? I wouldn’t know. I texted DJ, set down and picked up my phone, looked at my reflection in the mirror in front of me. I was skinny enough then to fit into a pencil jean skirt I can’t fit over my thighs anymore.

I was proud of myself for doing it, but relieved to escape across the street back to my apartment. How the hell did Nathan do it? How did he convince people he was worth their limited time, energy, and attention?

Maybe more than that — how did he convince himself?

DJ and I were already tipsy when we got off the 7 at Duval Center.

Quaint and placid, Duval Center is just an intersection on Duval St. in Hyde Park, the neighborhood that houses mostly grad students and young couples. It sports a gas station on one corner where DJ and I once withdrew $200 when my cards were stolen, a cute but pricey grocery store, Quack’s Bakery, which sells breakfast pastries 2 for 1 after 5 PM, Antonelli’s cheese shop, and a crop of restaurants that are nice enough for someone in their early 20s to feel sufficiently sophisticated taking their girlfriend to.

Ordering cocktails that were just as expensive as the meals themselves was enough to make DJ and I feel sophisticated. We took the bus so we could drink freely, and feeling loose and friendly we lingered a little too long at the counter making conversation with the pierced guy manning it. Looking down at the register, he paused.

“Do you guys live in the neighborhood?”

DJ and I looked at each other. “Yeah, pretty much,” I said.

He smiled. “I’ll give you the neighborhood discount.”

While we ate, he came over to us and left a scrap of paper on the table.

“That’s my Instagram,” he said.

When we came in again weeks later, he remembered us.

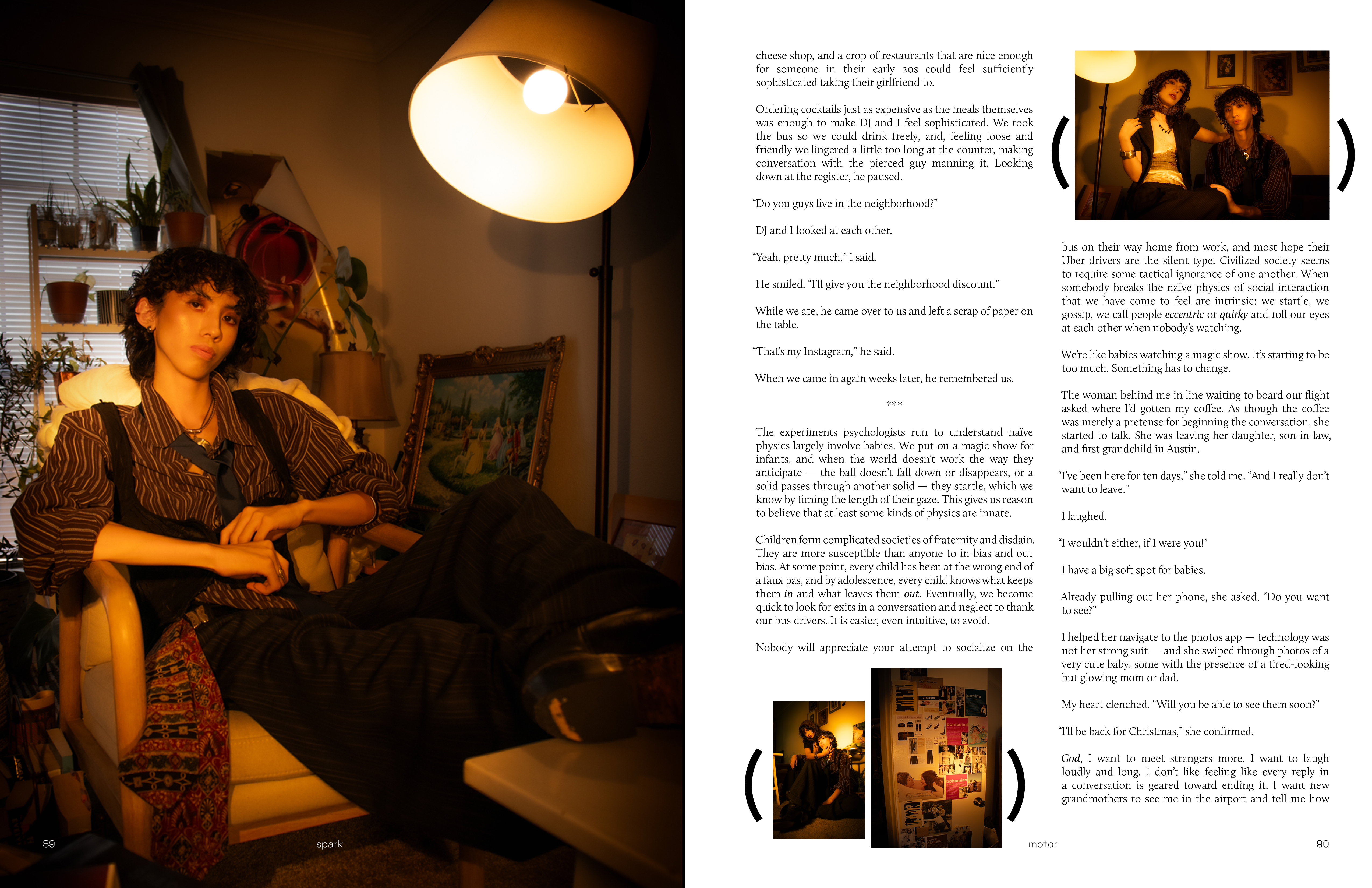

The experiments psychologists run to understand naïve physics largely involve babies. We put on a magic show for infants and when the world doesn’t work the way they anticipate — when the ball doesn’t fall down or disappears, or when a solid passes through another solid — they startle, which we know by timing the length of their gaze. This gives us good reason to believe that at least some kinds of physics are innate.

Children form complicated societies of fraternity and disdain. Children are more susceptible than anyone to in-bias and out-bias. At some point, every child has been at the wrong end of a faux pas, and by adolescence, every child knows what keeps them in and what puts them out. Eventually, we become quick to look for exits in a conversation and neglect to thank our bus drivers. It is easier, even intuitive, to avoid.

Nobody will appreciate your attempt to socialize on the bus on their way home from work, and most hope their Uber drivers are the silent type. Civilized society seems to require some tactical ignorance of one another. When somebody breaks the naïve physics of social interaction that we have come to feel are intrinsic, we startle, we gossip, we call people eccentric or quirky and roll our eyes at each other when nobody’s watching.

We’re like babies watching a magic show. It’s starting to be too much. Something has to change.

The woman behind me in line waiting to board our flight asked where I’d gotten my coffee. As though the coffee was merely a pretense for beginning the conversation, she started to talk. She was leaving her daughter, son-in-law, and first grandchild in Austin.

“I’ve been here for ten days,” she told me. “and I really don’t want to leave.”

I laughed. “I wouldn’t either, if I were you!” I have a big soft spot for babies.

Already pulling out her phone, she asked, “Do you want to see?”

I helped her navigate to the photos app – technology was not her strong suit – and she swiped through photos of a very cute baby, some with the presence of a tired-looking but glowing mom or dad.

My heart clenched. “Will you be able to see them soon?”

“I’ll be back for Christmas,” she confirmed.

God, I want to meet strangers more, I want to laugh loudly and long. I don’t like feeling like every reply in a conversation is geared toward ending it. I want new grandmothers to see me in the airport and tell me how they’re feeling.

It doesn’t even have to be me. I can just watch; I can be quiet and still, I can bear witness to some humanity.

The last days of spring break found me again at the Austin airport, teary-eyed from having to leave a grieving DJ in Austin. I sat down at my gate with my big stupid backpack near an older man with a thick crop of graying hair.

Pointing at me, he asked, “Greatest group ever?”

Nonplussed, I looked down. “I’m so sorry,” I laughed, the weight of tears sticky on my bottom lashes. “This is my boyfriend’s sweatshirt, but I’m sure he would think so.”

The middle-aged man sitting next to him, who had moments earlier asked to sit next to the gray-haired man and borrow his charger, had looked up and was already shaking his head.

“The Stones? Not the greatest group ever.”

As they began to bicker playfully about music, I sat, head down, and listened.

The younger man made a case for the Beach Boys.

The other said, “It’s good to have an open mind, but man, close it sometimes!”

The conversation gave way to talk about their lives. One of them was a sous chef. The other was moving to manage a basketball team in Italy. “I’ve done things with basketball that have never been done before,” he said.

When they parted ways, they clapped one another on the back and wished each other well. I sat, eyes wide, a baby whose idea of the world has been altered in some small but important way. The ache in my heart pulsed, as though reminding me that I had been sad, though momentarily distracted from my own private world of tragedy.

Lately, every small moment between strangers has been striking me as disproportionately significant. A girl on the bus making exaggerated, confused eye contact with me when the driver pulled over at the wrong stop; a woman with her dog saying, before a word had been spoken, “You can pet him!” Nothing earth shattering — just the small, mundane windows into people as complex and joyful and intricate as I. Avoidance might be the naïve physics of civilized society, but small talk is the love language of humanity.

I am trying to be brave: trying to make eye contact, linger in conversations, go to socials, be open to the flickers of gorgeousness behind the eyes of every person I come across.

Maybe it’s not realistic. Maybe it’s evolutionary, innate, unconscious. But why not try and break some laws today? ■

Layout: Chloe Romero

Photographer: Julius Gonzalez

Stylists: Chloe Romero & Angel Pena

HMUA: Averie Wang & Abhigna Bagepally

Modesl: Cat Roland & Aidan Vu

Other Stories in Motor

© 2025 SPARK. All Rights Reserved.