Pickton, TX

By Katie Chang

May 2, 2023

What business did hanfu-clad women and lotus gardens have in a 1940s Texan farmhouse?

Pickton, Texas, 2014.

The moment I stepped into the house, I wanted to leave. It was as if I’d entered a time capsule, but not the cool type: dingy overhead lighting made the popcorn ceiling super obvious, while wood paneling and red floral wallpaper made the place feel like a haunted dollhouse. It didn’t help that the wallpaper was Asian-themed — I thought the coincidence was a little weird.

Mom told us it was beautiful, but she said a lot of things that didn’t make sense.

We fought constantly — Mom had been away for most of the school year, and at 10, I found her intentions rather confusing. She claimed to want the best for everyone, but I’d watched Dad all year, sallow-faced and sad while he drove me around to all the places she’d always taken me to. If she loved us as she said, why would she leave us for a dusty farmhouse in the middle of nowhere?

It turns out that a decade of suburban housewifery had taken a toll on her, a naturally enterprising woman, and the real tragedy was neither her discarded career or failing marriage. It was her children. No matter how hard she tried to pass down the values instilled in her, her children were growing up to be American kids: kids who expect their lunch to be packed and rides to be covered, who only visit their grandparents during the holidays, who don’t learn what gratitude is until it’s too late.

So, she wanted to change things. I can’t quite recall what she told me, but I remember sitting on the couch the way she hated — on top of the back pillows — when she turned around in her desk chair.

“You know, Mommy grew up on a farm—”

“I know,” I interrupted. I knew where this was going; I had eavesdropped on her and Dad. “I'm not moving schools.”

“Don’t worry about that,” she said, changing the subject. “I found this place that’s not too far. It’s 120 acres and there’s a historic farmhouse right next to a church and…,” she trailed off.

“You know, lots of kids raise cows there. They even have a competition. You can win money if—”

“I’m not moving schools,” I interrupted again. “Also, raising a cow is weird.”

As it turns out, raising a cow is weird. It’s also difficult. But that was the point. The point of the farm was to teach us the things Mom learned in her childhood — the things we couldn’t learn from packed lunches and chauffeured rides. She wanted us to know the sulfurous stench of cow shit and the soreness from sowing fields and the stinging of the sun, because there is something beautiful about putting yourself into the fields and putting the fields into your animals and watching your animals bear offspring. There is something beautiful in watching your animals die, too, and returning them to the ground that had long fed them. To be a farmer is to bear witness to the rawest of life—to wake up each morning at the break of dawn and break your back feeding and feeding, but to sit down as the sun dips below the horizon knowing you’ll be fed back.

Or at least that is what Mom told me—I never did raise a cow.

***

Throughout the school year, Mom spent weeks restoring the farmhouse and sowing the ground for the growing season. Every so often, we’d meet her halfway at Cracker Barrel, where she’d tell us how cute the new piglets were and how many veggies she could grow once the USDA approved her grant request. As we’d part ways in the parking lot, she’d always say she wished to come back soon, but there was just so much work to do.

Only later would I realize that the work was much harder than she let on.

The house had been abandoned for a decade, and the family member who’d been helping grew disenchanted, leaving Mom to manage everything alone. Money was tight. Mom tried to come back home as often as possible, but it wasn’t easy — poor people in Pickton were never kind to a house left by city folks.

By the time the grass had grown tall and the piglets fat, I had graduated 5th grade.

***

One afternoon under the limelight of the late summer sun, I strode through the fields behind the house. The wind tangled my hair and tickled my nose with the smell of wild grass, and every step I took set a hundred grasshoppers aside; their wings fluttered in applause, their shrieks rang out in triumph. This was my royal procession, and in my hot pink Nike shorts and Dollar Tree rain boots, I was every bit a queen.

The next day, I was a country singer. Lounging around the chicken coop, I belted out Taylor Swift’s “Never Grow Up” while our dogs barked and my brother searched for eggs. The day after that, I was a bird, chasing my brother (who was a worm) around the church parking lot.

Outside of the house, I was free to be who and what I wanted to be, free from the sound of my parents bickering about finances and parenting philosophy. Outside, I could find plenty of ways to entertain myself.

Besides, no one could babysit but Mom, and she was constantly working.

Only once in a while would Dad come to visit, and those were the days Mom could hand him the handyman work and take us to pick veggies. It wasn’t easy work — my jet-black hair would burn under the sun and my hands would ache from scissors holes and bucket handles — but I recall one evening we all sat down for dinner made from our harvest.

“Mmm, do you taste how fresh the kale is?” Mom asked.

“I hate kale,” I said, my mouth filled with whatever at the table had carbs. In reality, I didn’t mind kale, but I couldn’t tell her that.

“Katherine. It’s good for your brain. Plus, this is the kale we picked.”

My brother perked up. “I like the kale!”

Mom smiled. “That’s mama’s boy. Katherine, even your brother is eating the kale.”

“I’ll eat the tomatoes.” I said.

A few minutes later, Dad spoke. He didn’t speak much at dinner.

“Looks like the AC is working well.”

“Yep,” Mom said. “You did a good job with it.”

Dad didn’t reply.

“Did the insurance company get back to you?”

Dad sighed. “No. I told you, the house is old—”

“I know. But someone will cover it.”

***

By mid-July the USDA was due to notify Mom about her grant application, but it seemed things were starting to work out on their own. Mom’s veggie garden was so abundant with produce we had to learn how to preserve it all — Mom canned tomatoes, my brother and I made kale chips, and in preparation for the upcoming farmer’s market, Mom bought a blank business name sign for us to decorate with veggie-people and cartoon cows.

At the end of the month, Mom received two manilla envelopes. One of them was the approval for the grant. The other was my Dad’s request for a divorce.

All Dad ever wanted was a wife, kids, and a steady job, and the moment Mom stepped onto the farm, bright-eyed and bold as the cattlemen before her, he knew his dream had come to an end. Every time he’d visit, he’d tell Mom how wonderful her progress was — the hardwood flooring looked great, the greenhouse was impressive — but the more Mom put herself into the farm, the less she left for him. He was losing her.

He didn’t want to lose us too.

Of course, Mom didn’t tell me anything. Dad didn’t either—he wasn’t there. He’d left a few days prior. Soon enough, his gray Honda Fit was in the church parking lot to retrieve me, and then I was home.

We never finished the sign for the farmer’s market.

***

Pickton, Texas, 2018.

Somewhere around Sulphur Springs on a drive back from the East, Dad turned to me from the driver’s seat.

“We’re pretty close to the farm,” he said. “Do you want to stop by?”

The farm. I, like all of us, avoided any mention of the place. Why would Dad want to visit it now?

“Sure,” I said.

As the sunset cast the world in soft red, we pulled into the church parking lot and headed towards the front door. Dad knocked. The new owners showered us in southern hospitality.

When I walked in, I expected to see the house I remembered. Mom said the new owners wanted everything as it was—my childhood desk in the bedroom with the patchwork wallpaper, the heater Mom stuck into the fireplace during the winter, even the collection of outdoor decor in the corner of the living room.

But I walked into an American home, Civil War paintings and all. The couches were covered in cowboy-style pillows, the walls in photos of family members and show horses. The only thing I recognized was the wallpaper, that garish wallpaper — fruit motifs for the dining room, florals for the bedrooms, red Chinoiserie for the living room.

I always thought the Chinoiserie was odd, even when I was 10. Really, what business did hanfu-clad women and lotus gardens have in a 1940s Texan farmhouse?

As it turns out, not much. ■

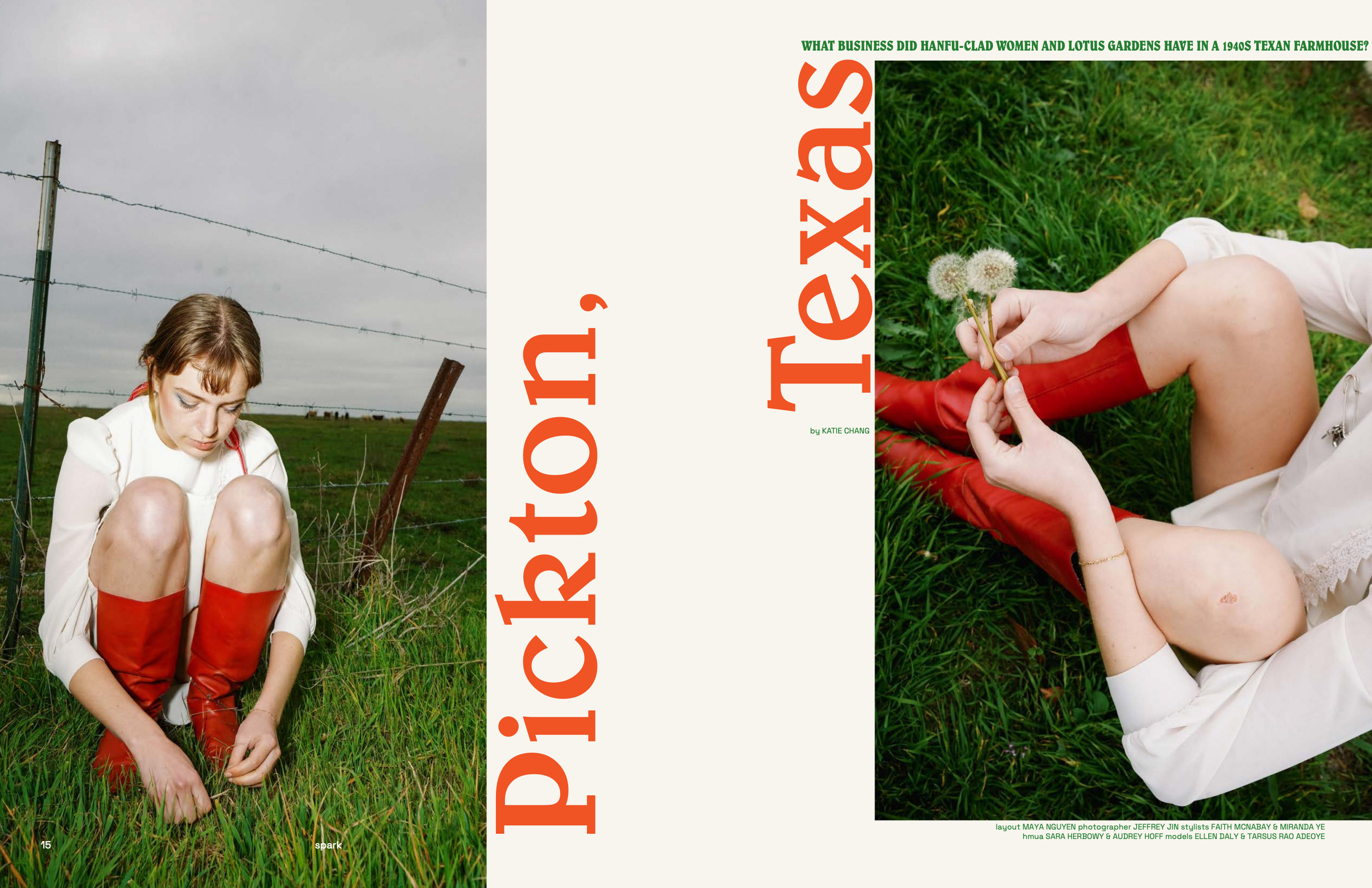

Layout: Maya Nguyen

Photographer: Jeffrey Jin

Stylists: Faith McNabay & Miranda Ye

HMUA: Sara Herbowy & Audrey Hoff

Models: Ellen Daly & Tarsus Rao Adeoye

Other Stories in Labyrinth

© 2025 SPARK. All Rights Reserved.