SANS ISSUE

| Good stories make bad lives. |

I’m writing the Next Great American Novel. I haven’t written the end yet, but I’m picturing something grand.

My protagonist is charming, if a bit strange. She’s this hedonist insomniac, the type to say yes to the after-party and the after-after-party and then whatever comes after that because something about walking home as the sky lightens feels romantic. She likes the moments life offers up little absurdities like sharing sidewalks with early risers entering the first hours of their day while she rounds out her last. She especially likes that she is the absurd one in this situation. It fills her with a sense of accomplishment, like a night lived to its fullest is a penny in the bank she will someday retrieve. To her, it is vital to be rich in experience.

She’s flighty, but it’s fine, because she’s more of a free spirit. She’s impulsive, but it’s okay, because she doesn’t really believe in regrets. She can’t commit, but it’s perfect, because she likes her life to be full of variety. Her story’s a little tragic, but not in a way that you feel sorry for her, just in a way that’s mysterious and adds emotional depth to her character.

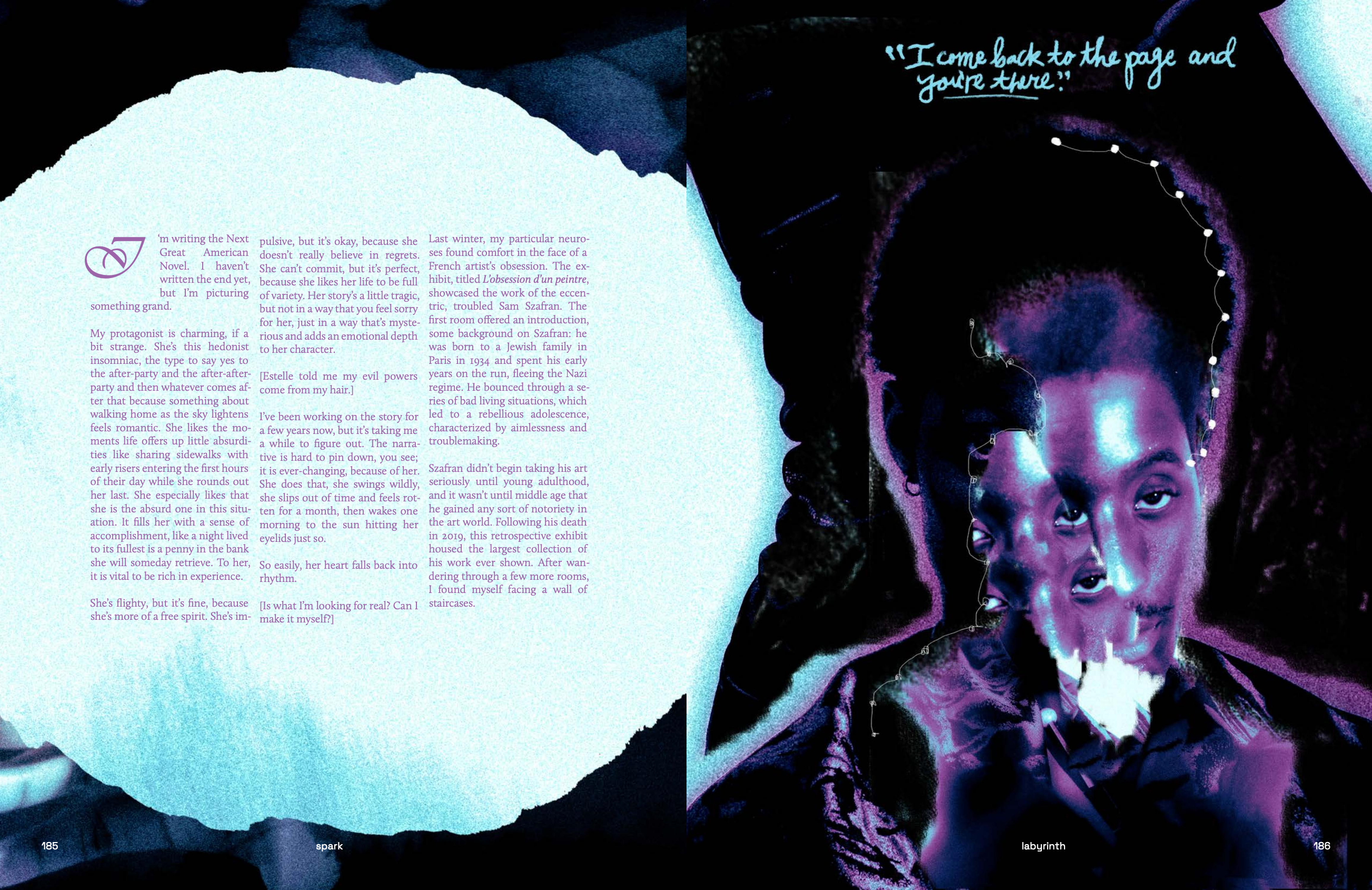

[Estelle told me my evil powers come from my hair.]

I’ve been working on the story for a few years now, but it’s taking me a while to figure out. The narrative is hard to pin down, you see; it is ever-changing, because of her. She does that, she swings wildly, she slips out of time and feels rotten for a month, then wakes one morning to the sun hitting her eyelids just so. So easily, her heart falls back into rhythm.

[Is what I’m looking for real? Can I make it myself?]

Last winter, my particular neuroses found comfort in the face of a French artist’s obsession. The exhibit, titled L’obsession d’un peintre, showcased the work of the eccentric, troubled Sam Szafran. The first room offered an introduction, some background on Szafran: he was born to a Jewish family in Paris in 1934 and spent his early years on the run, fleeing the Nazi regime. He bounced through a series of bad homes and cruel authority figures, which led to a rebellious adolescence, characterized by aimlessness and troublemaking.

Szafran didn’t begin taking his art seriously until young adulthood, and it wasn’t until middle age that he gained any sort of notoriety in the art world. Following his death in 2019, this retrospective exhibit housed the largest collection of his work ever shown. After wandering through a few more rooms, I found myself facing a wall of staircases.

There is so much to say about Szafran’s spiraling staircases. They bend and collide, pare down to thin lines, balloon into cubic panoramas. I’d never seen anything like it. The placards beside paintings revealed an even more dizzying truth: Szafran fashioned these stairwells, modeled after one in his Parisian apartment building, to reflect the terror he experienced as a young boy,when an uncle he’d been living with dangled him by his ankles above the stairwell — cruelly, to inject fear.

Framed by this context, the works allude to an obsession with perfection informed by a childhood lack of autonomy and control. Szafran’s staircases, endless and beautiful as they may be, possess one unifying quality: we cannot see a way out. They end and begin someplace beyond our perspective. Though he replicated them over and over and over again, he could never draw himself an exit. And so he was condemned.

[It’s just getting started, you know.]

The obsession that drove him to create and recreate, to capture it and capture it differently than anyone else, felt like the obsession that drives me to fill pages in notebooks with slightly different descriptions of the same smile.

[I’m not sure what I believe will happen when I finally find the right combination of words to convey the curl of your lip, but I come back to the page and you’re there.]

To frame a collection of art through the lens of the artist’s obsession invites an exploration of the nature of artistic expression — how does shaping it into a disciplined practice affect the psyche? An artist striving for perfection has assigned themselves the impossible task of capturing the ephemeral. No wonder they have a reputation for going mad.

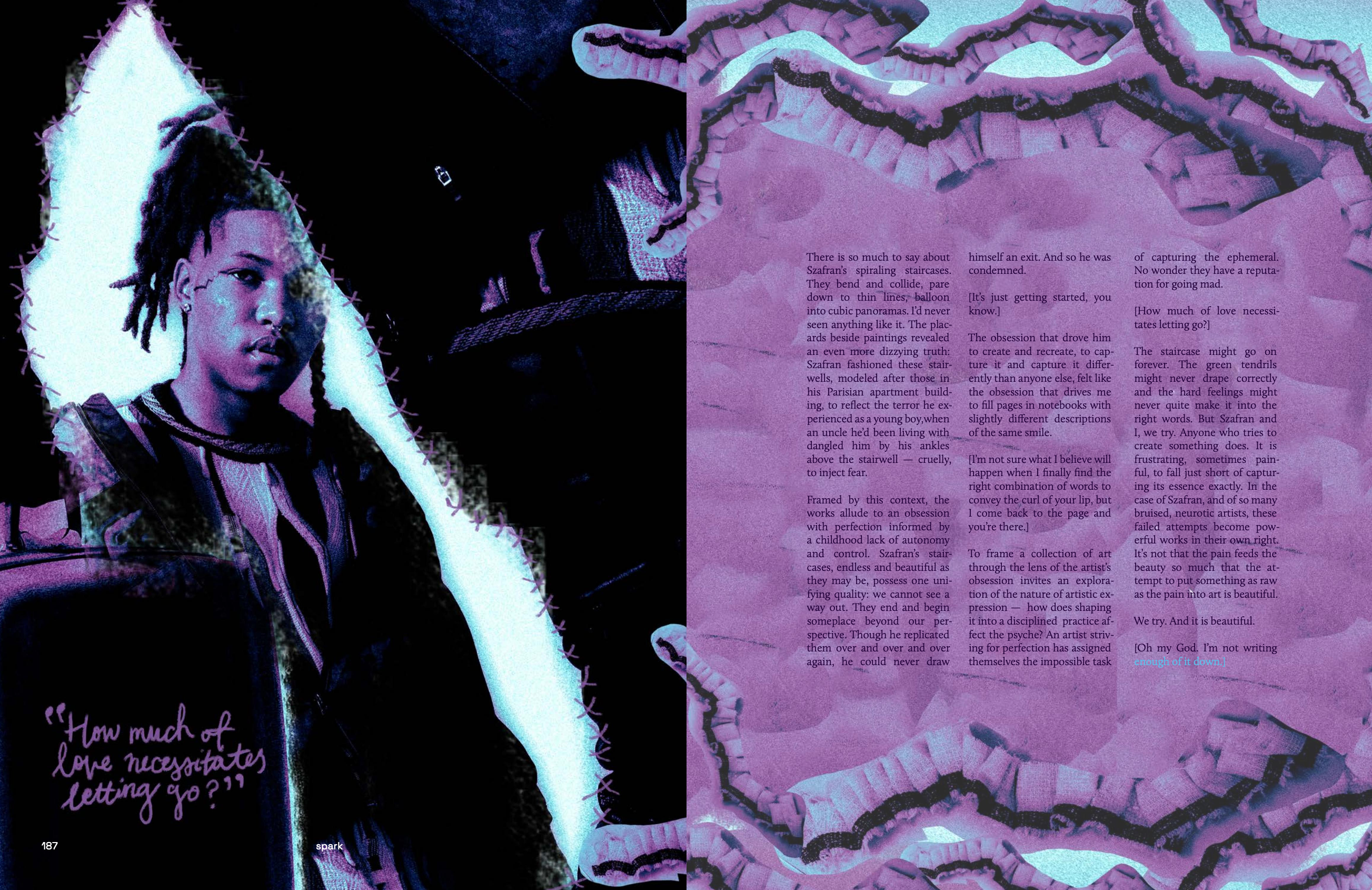

[How much of love necessitates letting go?]

The staircase might go on forever. The green tendrils might never drape correctly and the hard feelings might never quite make it into the right words. But Szafran and I, we try. Anyone who tries to create something does. It is frustrating, sometimes painful, to fall just short of capturing its essence exactly. In the case of Szafran, and of so many bruised, neurotic artists, these failed attempts become powerful works in their own right. It’s not that the pain feeds the beauty so much that the attempt to put something as raw as the pain into art is beautiful.

We try. And it is beautiful.

[Oh my God. I’m not writing enough of it down.]

Walk a little further, turn the gallery corner. There is Lilette, Szafran’s wife, draped in a red kimono and framed by a gargantuan rhododendron. Its leaves take many shades and forms — greens and blues, delicate and sweeping, frantic and crazed. But there again is Lilette, appearing over and over, a lover-shaped anchor in the sea of his obsession. His desire for perfection surrounds her, engulfs her — made virtuous by her presence.

Flip the page. There you are, shaped in musings and in memories, inked in mornings-after and nights-before. There you are, fresh as I could catch you. I never think much about the things I am capturing in writing until I return to them and they’re all I have left. Each page reads so much more to me than what I’ve remembered to write down. Between moments of despair, in blank stretches, there is love. In scrawled grocery lists, there is care. In the way I paint your name, curling the end of each letter with flair, there is something inexpressible being expressed.

[The leaves have all changed color without my noticing. Somewhere in between dreary rooms, the green outside burst into candylike shades of orange and red and yellow.]

I’m writing the Next Great American Novel. My protagonist has no fucking clue what she’s doing.

[And so it begins.] ■

Layout: Sriya Katanguru

Photographer: Dylan Haefner

Stylists: Saturn Eclair & Summer Sweenis

HMUA: Claire Philpot

Model: Jereamy Hall & Brandon Akinseye

Other Stories in Labyrinth

© 2025 SPARK. All Rights Reserved.