That Freeway

May 2, 2023

| Control is power, and though it’s a delusion, it’s magnetic. |

That freeway existed long before Maeve and Erin were born and long after W.D. Bedell and Erin died.

That freeway was the first freeway to exist in Texas. It was unveiled in 1948 with an anonymity that seemed strange for how impossible it was to ignore. That freeway pounded and drilled and stretched its limbs as it displaced Houstonians in poor neighborhoods and stirred excitement in businessmen–and yet–when it was unveiled, it had no name. Some newspapers came to call it the Interurban Expressway, poor people just called it “that damned road," and later that year, Miss Sara Yancy of the Houston Heights won $100 for calling it the Gulf Freeway in a naming contest.

So, it is the Gulf Freeway for a while.

It is the Gulf Freeway when W.D. Bedell writes about it in 1957. Bedell’s position as a columnist for the Houston Post runs on the waning power of a personal favor. He battles a popular radio show that sensationalizes the American Dream, because apparently only one segment can. Bedell believes writing does something speaking can’t do, and he intends to prove it to that radio show, to that boss losing faith in him, and to you.

Bedell is at the unveiling in 1948, when that freeway is exciting.

A group of five hundred is swallowed by the vastness of that freeway and the flat space that expands out on all sides of it. Mayor Oscar Holcombe gives a speech about progress and plays “Happy Days are Here Again,” on a phonograph. The music loses its volume as it travels into flatness. To Bedell, it’s like an eerie baby shower for something big. It doesn’t have predecessors or a name, but there is a sense it is something. That freeway makes him feel anxious yet imperceptibly excited perhaps because he can raise and name that something by immortalizing it in his image.

By the summer of 1992, when Maeve drives up that freeway to Erin’s house for the summer, it is called I-45.

Maeve and Erin have spent many summers together. They’re cousins related on their mother’s sides. Maeve lives immediately off the left side of I-45, universally known as the poor side. Erin lives in the nicer suburb, the right side.

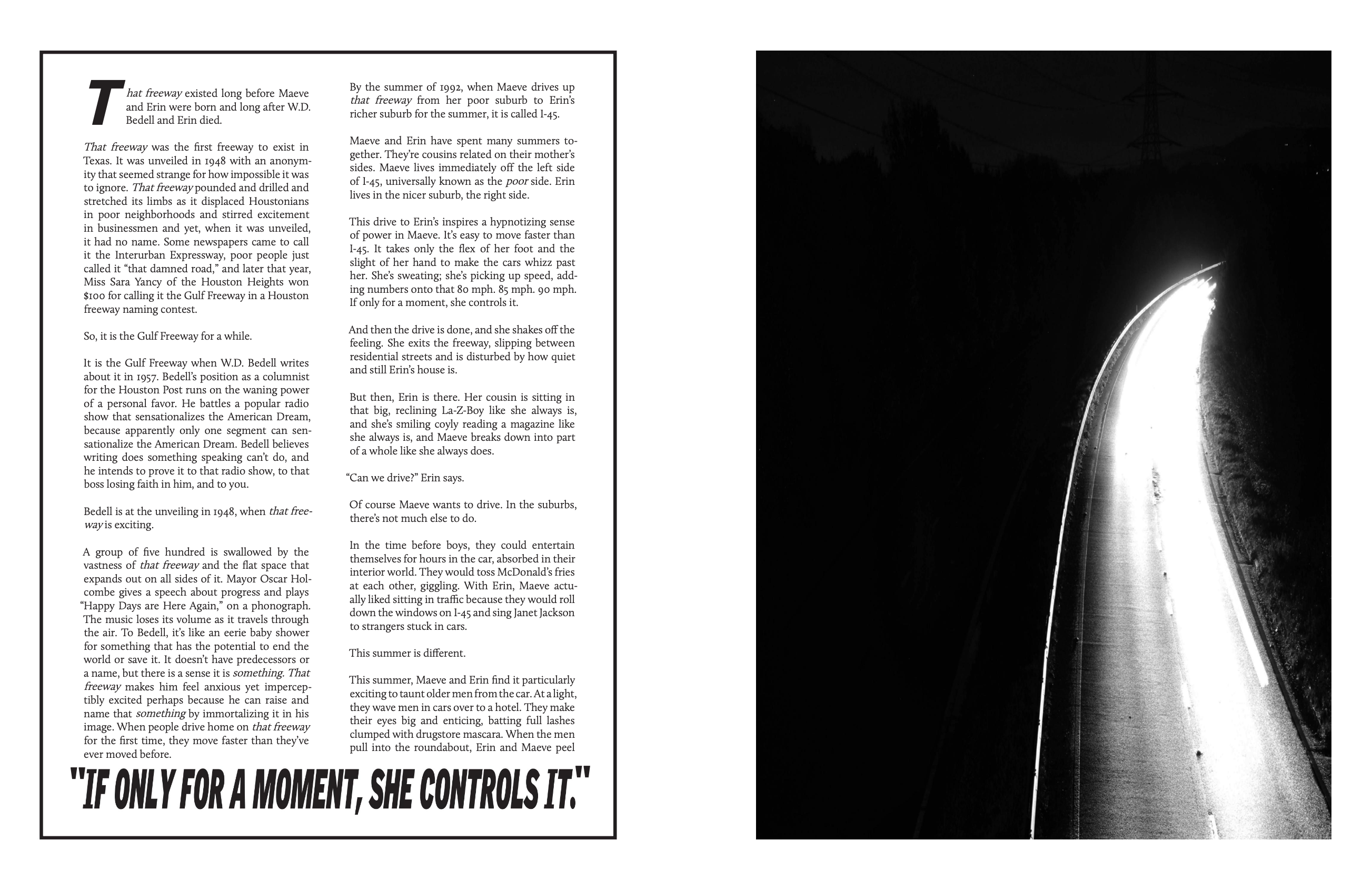

This drive to Erin’s inspires a hypnotizing sense of power in Maeve. It’s easy to move faster than I-45. It takes only the flex of her foot and the slight of her hand to make the cars whizz past her; she’s sweating; she’s picking up speed, adding numbers onto that eighty mph. Eighty-five mph. Ninety mph. If only for a moment, she controls it.

And then the drive is done, and she shakes off the feeling. She exits the freeway, slipping between residential streets and is disturbed by how quiet and still Erin’s house is.

Maeve walks up the concrete steps with careful gentleness so as not to break them, and opens the door. She’s there, Erin is there, and Maeve's anxieties dissolve upon crossing this threshold where concrete meets something human. Her cousin is sitting in that big, reclining La-Z-Boy like she always is, and she’s smiling coyly reading a magazine like she always is, and Maeve melts into part of a whole like she always does.

“Can we drive?” Erin says.

Of course Erin wants to drive; in the suburbs there’s not much else to do.

In the summers before boys, they could entertain themselves for hours in the car, absorbed in their interior world. They would toss McDonald’s fries at each other, giggling. With Erin, Maeve actually liked sitting in traffic because they would roll down the windows on I-45 and sing Janet Jackson to strangers stuck in cars.

This summer is different.

This summer, Maeve and Erin find it particularly exciting to taunt older men from the car. At a light, they wave men in cars over to a hotel. They make their eyes big and enticing, bating full lashes clumped with drugstore mascara. When the men pulled into the roundabout, Erin and Maeve peel out, laughing like girls. Their laughter hangs in the air after they roll up their windows to coast down I-45. Maeve turns in the passenger seat to face Erin.

“Has anything happened with the boyfriend yet?”

Maeve, at the time, was curious about Erin’s boyfriends. Maeve dated guys her age, but Erin’s guy was older. To Erin, the notion of having sex with him seemed much more exciting when she was doing things like applying mascara in the mirror or reading magazines barefoot on the Lay-Z-Boy. Maeve’s mention of him outside of something future and speculative was gross. Of course when she responds to Maeve, she frames her answer as a joke — a funny addition to the things they liked and disliked about the new and curious things happening with men.

By 1992, that freeway was very different than in 1948 and 1957. In 1992, it was suffocating underneath writhing overpasses that stacked and stumbled over one another.

Where the overpasses fell, they bled into commercial centers and swallowed tiny towns. The freeways had to grow to survive. Their existence depended on continuous expansion, and if the towns got too big to exist independently of the city’s resources, the freeways were unnecessary and left behind. It is for that reason Houston bears the marks of its growth like stretch marks on a body that grows too quickly to contain itself, looped by 610, then Beltway 8, then Highway 99.

For a while, though, that freeway did shine. It shone brightly in 1957 when cars moved through space unencumbered by future outlet malls and gated communities. When it was the Gulf Freeway, the road buzzed with potential energy. As the cars drove over it, they could feel the future coming. W.D. Bedell was the one who was going to eternalize it.

He exits, slowing the car. He’s brought a multi-colored, rusting lawn chair and a typewriter with him. He parks the car in the grass bordering the road. He unfolds his chair, lifts his suit pants, and sits facing I-45 with a typewriter on his lap. He sits without knowing when he will move again. He begins to type, This is Houston. It is a city that refuses to stand still for anybody…

In the summer of 1993, the boyfriend stumbles to the right side of the car and opens the door for Erin. She concedes that sly, sideways smile and guides her lanky, slumping limps into the passenger seat. The boyfriend reverses.

…It is a city where the old except in its sturdiest forms quickly disappears, in which the new quickly becomes the old, in which change is relentless and rushing…

The boyfriend merges onto I-45. The alcohol does something strange to the course of the night; they dance around control and their lack of it — a hand on the wheel, a contained car on an open road. He moves across four lanes in a string of jerky motions, just missing a car.

…It is a city on the move, with few to observe its movement, for most of its citizens are moving with it, moving too swiftly to stand aside and watch…

Erin knows Maeve doesn’t like or trust this older boyfriend, but she covers for Erin anyway. With blurred vision, Erin looks at him: this boyfriend, driving. She drinks in his movements: the way his fingers grip and loosen, the way he looks toward her. Erin does not love this boyfriend, but she loves when he looks at her like this: not at or into her, but toward her. It’s like she wields some internal magnetic force; it doesn’t matter to him where it emanates from so long as he may run over it again, and again. More exhilarating to Erin is the sense that she has sitting in the passenger seat. It’s a concoction of being free, and rich, and high, and drunk, and alive. Those things texture the air with a feeling like love.

…Pause, if you safely can, somewhere beside the Gulf Freeway…

The boyfriend sees that she’s enjoying herself, so he speeds up and Erin laughs. Eighty, then eighty-five. She laughs first to make him feel secure, and he smirks. Then it becomes funny how reactive he is to her, how weak he looks in the driver’s seat, and she throws her head back and laughs harder. A raspy, deep laugh, like she’s gurgling asphalt. Erin is reclined, looking up at the sunroof, liking the feeling of being dizzy with the velocity of the car. She feels light. In this moment where control has been ceded, Erin is most powerful; she feels divine; she is the first person, the only person, to be completely absolved from limits of her corporeality.

…The movement will dazzle you…

The overhead fluorescent lights burn an artificial orange against an otherwise black night. The houses dotting the frontage road emanate faint yellow lights that look like a chemtrail tracing her path. She stares at the blur, and it begins to feel sad and untrue. The boyfriend has stopped watching her.

…But do not stand still for too long, you might get run over. Or what is worse, in Houston, you surely will get left behind…

The boyfriend was going ninety when he hit the barrier. At that moment, in 1993, Maeve was asleep in Erin's bed. W.D. Bedell was under the ground, weighed down by the perennial motion of cars above him. And the freeway, rather impersonally, had expanded but never moved and did not intend to. ■

Layout: Leilani Cabello

Other Stories in Labyrinth

© 2024 SPARK. All Rights Reserved.