The High Priestess

May 2, 2023

Through her, I found the strength to embrace my own madness, and the freedom that comes with it.

Everyone tells you not to be in a relationship during your freshman year of college. I ignored that advice, as I usually do to most, and threw myself into one for an entire year and a half before it came tumbling down.

The night my world seemed to end, I screamed at her, threw her clothes down the trash chute, and stole her keys to stop her from leaving. The day’s final hours concluded with me sitting in a frigid waiting room at the local emergency center, cheeks stained pink with tears and the remnants of my hysteria.

Things got worse before they got better. My trip back to my hometown for Thanksgiving break brought forth days during which I was unable to eat, or do much more than wallow in the comforting confines of my plush childhood bed. Slowly but surely, after days during which a hollow emptiness had begun to settle within me, the end of the week came, and I was on my way back to the comfort of my college apartment. I sat on my cheap Amazon rug with bloodshot eyes and tear-stained cheeks, staring at my tarot deck.

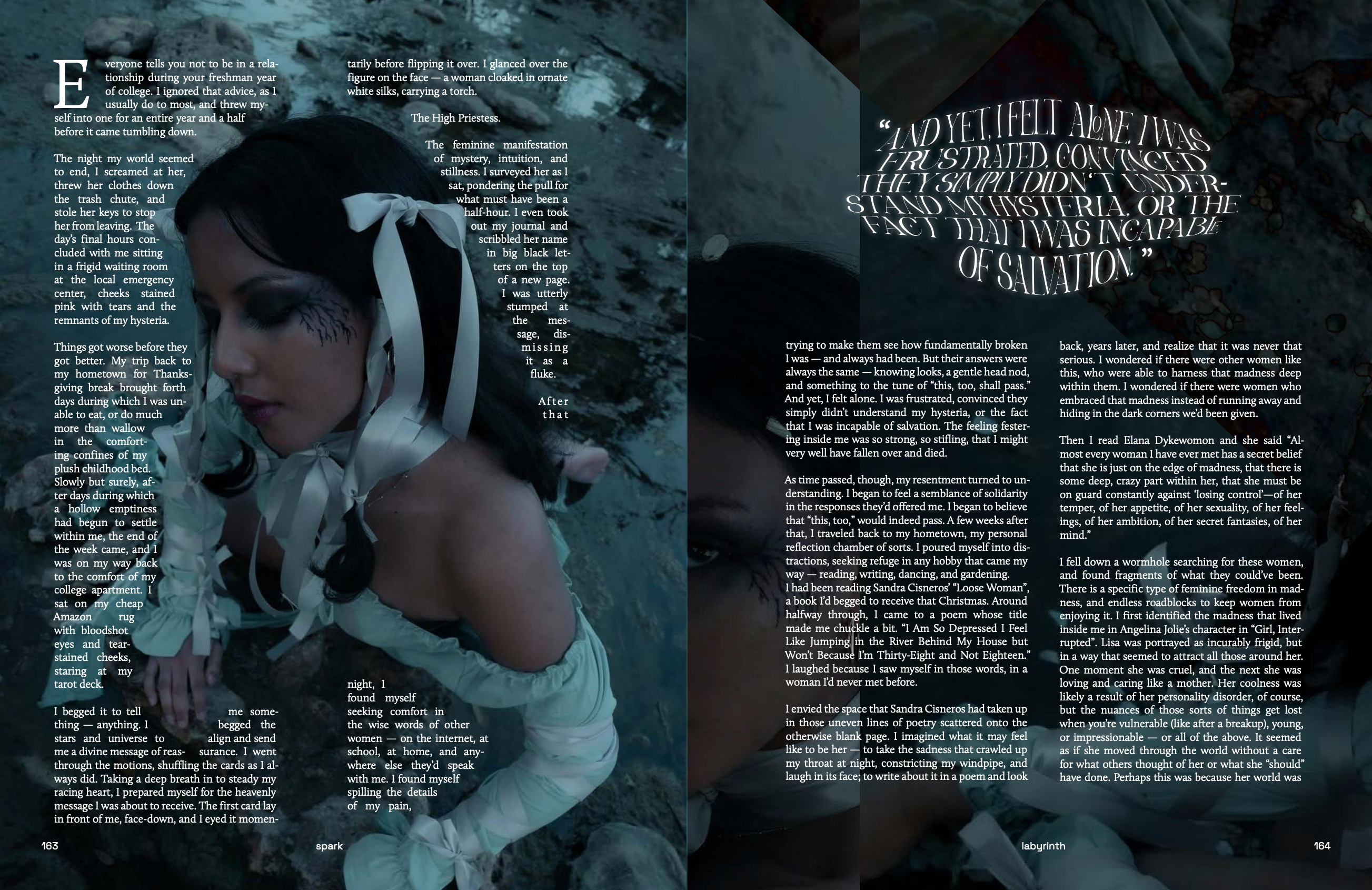

I begged it to tell me something — anything. I begged the stars and universe to align and send me a divine message of reassurance. I went through the motions, shuffling the cards as I always did. Taking a deep breath in to steady my racing heart, I prepared myself for the heavenly message I was about to receive. The first card lay in front of me, face-down, and I eyed it momentarily before flipping it over. I glanced over the figure on the face — a woman cloaked in ornate white silks, carrying a torch.

The High Priestess.

The feminine manifestation of mystery, intuition, and stillness. I surveyed her as I sat, pondering the pull for what must have been a half-hour. I even took out my journal and scribbled her name in big black letters on the top of a new page. I was utterly stumped at the message, dismissing it as a fluke.

After that night, I found myself seeking comfort in the wise words of other women — on the internet, at school, at home, and anywhere else they’d speak with me. I found myself spilling the details of my pain, trying to make them see how fundamentally broken I was — and always had been. But their answers were always the same — knowing looks, a gentle head nod, and something to the tune of “this, too, shall pass.” And yet, I felt alone. I was frustrated, convinced they simply didn’t understand my hysteria, or the fact that I was incapable of salvation. The feeling festering inside me was so strong, so stifling, that I might very well have fallen over and died.

As time passed, though, my resentment turned to understanding. I began to feel a semblance of solidarity in the responses they’d offered me. I began to believe that “this, too,” would indeed pass. A few weeks after that, I traveled back to my hometown, my personal reflection chamber of sorts. I poured myself into distractions, seeking refuge in any hobby that came my way — reading, writing, dancing, and gardening.

I had been reading Sandra Cisneros’ Loose Woman, a book I’d begged to receive that Christmas. Around halfway through, I came to a poem whose title made me chuckle a bit. “I Am So Depressed I Feel Like Jumping in the River Behind My House but Won’t Because I’m Thirty-Eight and Not Eighteen.” I laughed because I saw myself in those words, in a woman I’d never met before.

I envied the space that Sandra Cisneros had taken up in those uneven lines of poetry scattered onto the otherwise blank page. I imagined what it may feel like to be her — to take the sadness that crawled up my throat at night, constricting my windpipe, and laugh in its face; to write about it in a poem and look back, years later, and realize that it was never that serious. I wondered if there were other women like this, who were able to harness that madness deep within them. I wondered if there were women who embraced that madness instead of running away and hiding in the dark corners we’d been given.

Then I read Elana Dykewomon and she said “Almost every woman I have ever met has a secret belief that she is just on the edge of madness, that there is some deep, crazy part within her, that she must be on guard constantly against ‘losing control’—of her temper, of her appetite, of her sexuality, of her feelings, of her ambition, of her secret fantasies, of her mind.”

I fell down a wormhole searching for these women, and found fragments of what they could’ve been. There is a specific type of feminine freedom in madness, and endless roadblocks to keep women from enjoying it.

I first identified the madness that lived inside me in Angelina Jolie’s character in Girl, Interrupted. Lisa was portrayed as incurably frigid, but in a way that seemed to attract all those around her. One moment she was cruel, and the next she was loving and caring like a mother. Her coolness was likely a result of her personality disorder, of course, but the nuances of those sorts of things get lost when you’re vulnerable (like after a breakup), young, or impressionable — or all of the above. It seemed as if she moved through the world without a care for what others thought of her or what she “should” have done. Perhaps this was because her world was confined to the boundaries of an inpatient psychiatric facility. She had already been labeled “mad”, so there were no more expectations for her to follow. She could laugh wildly, cry wholeheartedly, scream violently, and exist in the freedom of those expulsions.

Such freedom seemed unattainable to me, but I soon realized that women like me seek strength in numbers. In the depths of my depression, I found solace through the similarity of me and these other women — these mad, hysteric women.

What does it mean to be one, anyway? I thought of the example my mother had given me, which I was never explicitly told, but rather observed through the lens of a naive child. To be a woman was to be caring to a fault, and to give and give until there was hardly any of you left for yourself. To be a woman meant being a good daughter until you were a good wife until you were a good mother. I felt the muted sparkles of womanhood in the moments when their mothers pulled too roughly at their hair, or at the comforting touch of another woman while crying, but also in the harshly lit fitting room mirrors as I poked and prodded my body, distorted by too-tight clothing. I knew the women in the stalls next to me were likely doing the same: poking, prodding, and frowning at the rolls of their bellies or stretch marks on their thighs, hoping to somehow do something to change it at that moment. They couldn’t, though. Neither could I. My body was marred by my mind. My body was my cage.

Why is the extent of our sense of community built on our collective pain? Why do I have to accept the lot I was given, and be forever condemned and looked down upon by critical peers for the same emotions that surely live in them? Why is being a woman a life sentence of suffering?

A few weeks later, as life would have it, I was brought back to my tarot deck. Back where I’d been before — on that damned green rug — I shuffled the cards briefly before pausing, reconsidering my intentions. I had no pressing questions, none that they could answer for me, not this time. I fanned the cards out face-up in front of me. It took a few moments for my eyes to scan the deck. I thought back to the High Priestess — her eyes solemnly staring back at me. She seemed...

Lonely.

She was the ideal, meant for us to strive towards becoming, so why did she look so sad? Was it truly lonely at the top?

To be a woman is to suffer. To be mad is the bravest choice a woman could make because she dares to reject that suffering, despite the consequences she knows she will face. She knows she will be ostracized, rejected, and criticized. She knows the other women in her life will trade knowing whispers behind her back, and others will scoff at her when she passes. She knows all of this, and she dares to embrace her madness anyway, because she knows the path to divinity is paved with the freedom it brings.

The High Priestess represents the divinely feminine ideal, one that is at once elusive and terrifying. She embraces the madness, living unabashedly and moving through the world with utter confidence. She is all at once Lisa and Sandra and Me.

She is a mad woman, and I yearn to become her. ■

Layout: Melanie Huynh

Photographer: Liv Martinez

Stylist: Emily Wager

HMUA: Dakota Evans

Model: Stacey Campbell

Other Stories in Labyrinth

© 2025 SPARK. All Rights Reserved.