Windows

By Katie Chang

December 5, 2022

As we turn to digital nature, what happens to our relationship with the real, physical thing?

My family never flies.

We’re the road trip type. The camping and eating freeze dried spaghetti kind of family. We drive for hours and hours on end, and I rotate between scrolling on my phone and staring out the window as one version of White Sands blurs into the next, on and on and on. The landscape seems to unfold endlessly—it feels like we’re making no progress.

There are 473k more pictures under #whitesands. I guess we aren’t.

***

For about 95% of our species’ existence, we survived as hunter-gatherers, in tune with the natural world. We knew we were at the mercy of nature’s order, and calculated our every action accordingly. We followed the ebb and flow of the seasons, navigating the land with the intent to survive—just as other species did.

At some point, some luck-of-the-draw combination of factors (a shift in environmental patterns, a larger brain, and a big toe, perhaps?) allowed for the development of agriculture, and from there, our relationship with nature changed. It was no longer something we were both a part of and subject to. We could interrupt the natural seed dispersal process to get more wheat! We could fence up a group of pigs to have readily-available meat! Nature became something to dominate, something to control to fulfill our needs.

As mud villages turned into concrete cities and human labor turned into machine, the same regard for nature that enabled our mastery of agriculture sowed the seeds of capitalism. Our wheat dispersal hack is now a billion-dollar fertilizer industry. Our pig pen is a trillion-dollar meat market. From the comfort of our leather desk chairs in our glass high-rises, we’ve cemented our role as nature’s puppeteer, and in doing so, we’ve sucked the life out of Earth’s soil and ripped apart its atmosphere.

Yet, somewhere deep within our psyche, we know we’re missing something. Somewhere not yet poisoned by the gospel of economic growth, our primordial affiliation with nature survives.

So, to recreate what we have destroyed, we turn to technology. “Digital nature.” Virtual reality is on the rise. Video games featuring mythical woods and majestic mountains are more popular than ever. We can experience an outdoor run via an indoor treadmill. We can explore pristine beaches and luscious forests via #nature.

And the best part? We get to create it all ourselves. With cameras and desktops that offer the newest and greatest computational abilities, we can make digital nature just like the real, physical thing.

But when we watch hiking vlogs or experience virtual reality, we can only see the river flow and the trees sway. We do not feel the wind or smell the soil. We hear the sky thunder and the bushes rustle. But we don’t have to listen, because we aren’t worried about a storm approaching or a bear lurking around the corner. We know we aren’t at the mercy of the nature we experience because we created it all — it's under our control.

And that’s the problem. Inherent to nature is the process of living in relation with the other, not in domination over it. Digital nature, as a human creation—a product of our utmost control—is not the same. It doesn’t even come close. Its very existence is contradictory to nature itself.

Our attempt to recreate what we have destroyed is not only futile—it’s destructive. Digital nature is an extension of the exact phenomenon that elicited its necessity.

***

Smooth mounds of white gypsum blend into the painterly sky. The half-shrouded sun creates a soft glow over the deep blue mountains.

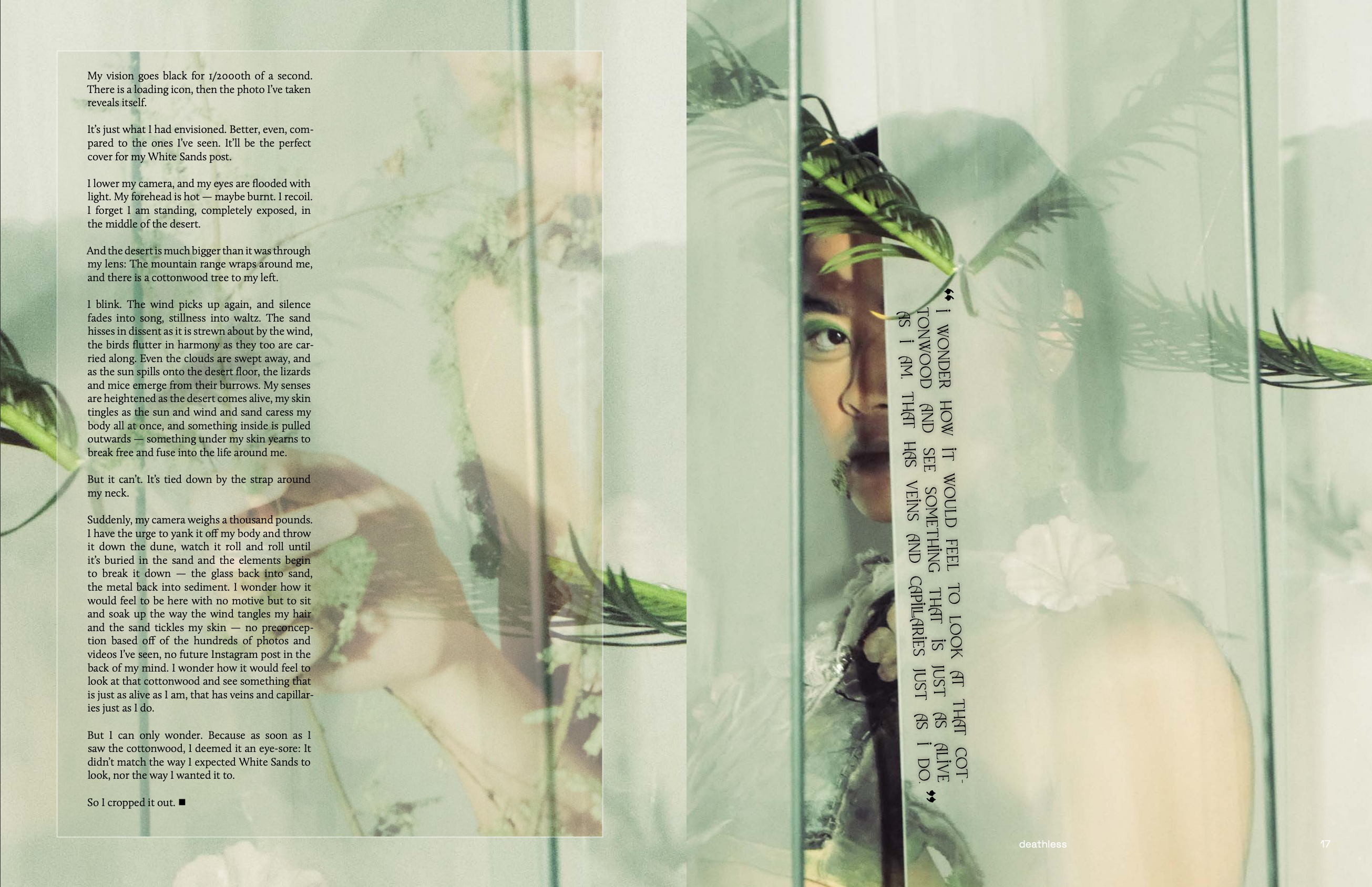

My vision goes black for 1/2000 of a second. There is a loading icon, then the photo I have taken reveals itself.

It’s just what I had envisioned. Better, even, compared to the ones I’ve seen. It’ll be the perfect cover for my White Sands post.

I lower my camera, and my eyes are flooded with light. My forehead is hot—maybe burnt. I recoil. I forget I am standing, completely exposed, in the middle of the desert.

And the desert is much bigger than it was through my lens: the mountain range wraps around me and there is a cottonwood tree to my left.

I blink. The wind picks up again, and silence fades into song, stillness into waltz. The sand hisses in dissent as it is strewn about by the wind, the birds flutter in harmony as they too are carried along. Even the clouds are swept away, and as the sun spills onto the desert floor, the lizards and mice emerge from their burrows. My senses are heightened as the desert comes alive, my skin tingles as the sun and wind and sand caress my body all at once, and something inside is pulled outwards—something under my skin yearns to break free and fuse into the life around me.

But it can’t. It’s tied down by the strap around my neck.

Suddenly, my camera weighs a thousand pounds. I have the urge to yank it off my body and throw it down the dune, watch it roll and roll until it is buried in the sand and the elements begin to break it down—the glass back into sand, the metal back into sediment. I wonder how it would feel to be here with no motive but to sit and soak up the way the wind tangles my hair and the sand tickles my skin—no preconception based off of the hundreds of photos and videos I’ve seen, no future Instagram post in the back of my mind. I wonder how it would feel to look at that cottonwood and see something that is just as alive as I am, that has veins and capillaries just as I do.

But I can only wonder. Because as soon as I saw the cottonwood, I deemed it an eye-sore: it didn’t match the way I expected White Sands to look, nor the way I wanted it to.

So I cropped it out. ■

Layout: Melanie Huynh

Photographer: Tyson Humbert

Videographer: Athena Polymenis

Stylist: Summer Sweeris

Set Stylist: Caroline St. Clergy

HMUA: Lily Cartenega

Model: Laurence Nguyen-Thai

Other Stories in Deathless

A World Where No One Dreamed

By Rachel Bai

December 5, 2022

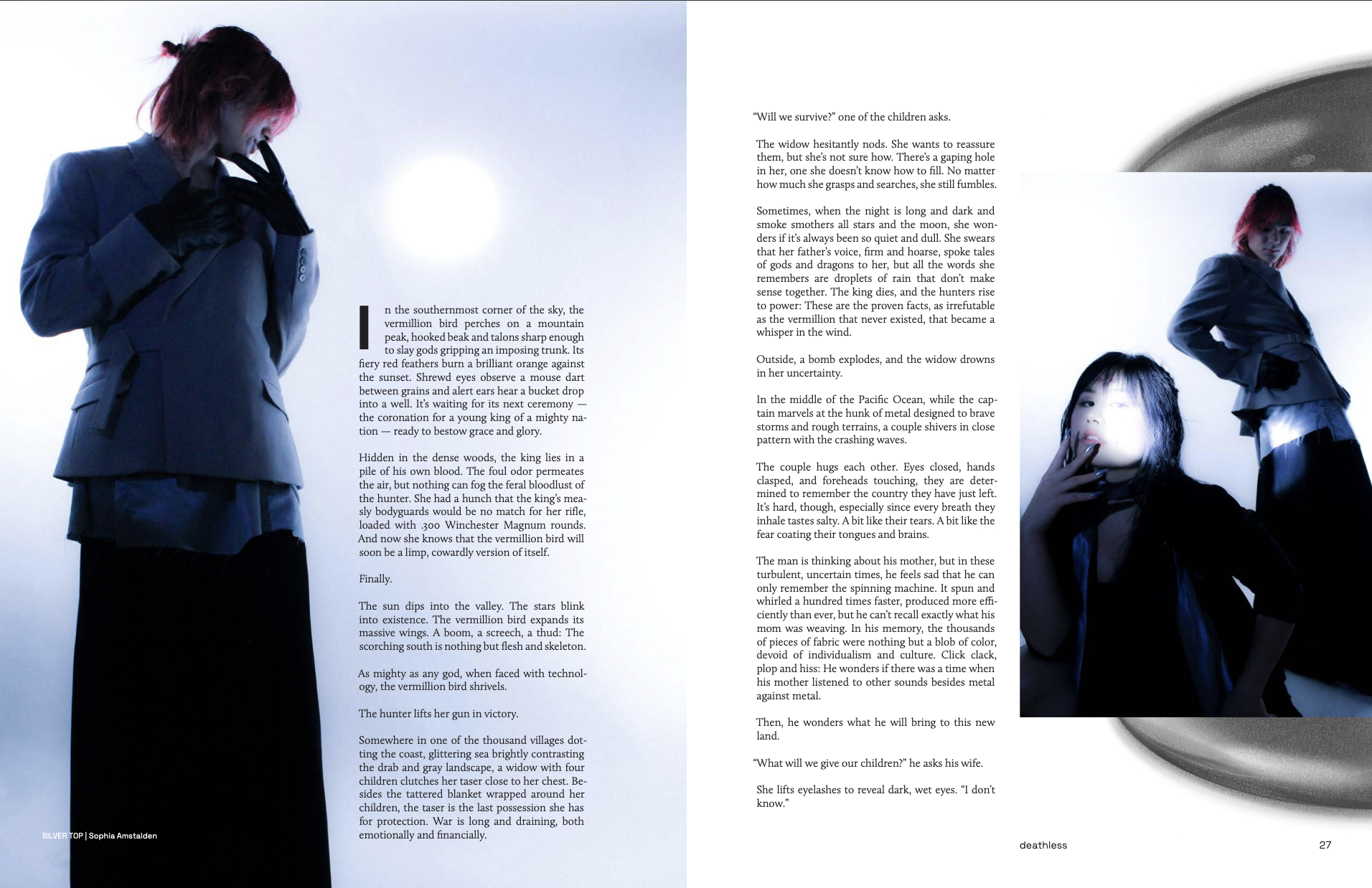

In the southernmost corner of the sky, the vermillion bird perches on a mountain peak, hooked beak and talons sharp enough to slay gods gripping an imposing trunk. Its fiery red feathers burn a brilliant orange against the sunset. Shrewd eyes observe a mouse dart between grains and alert ears hear a bucket drop into a well. It’s waiting for its next ceremony — the coronation for a young king of a mighty nation — ready to bestow grace and glory.

Hidden in the dense woods, the king lies in a pile of his own blood. The foul odor permeates the air but nothing can fog the feral bloodlust of the hunter. She had a hunch that the king’s measly bodyguards would be no match for her rifle, loaded with .300 Winchester Magnum rounds. And now she knows that the vermillion bird would soon be a limp, cowardly version of itself.

Finally.

The sun dips into the valley. The stars blink into existence. The vermillion bird expands its massive wings. A boom, a screech, a thud: The scorching south is nothing but flesh and skeleton.

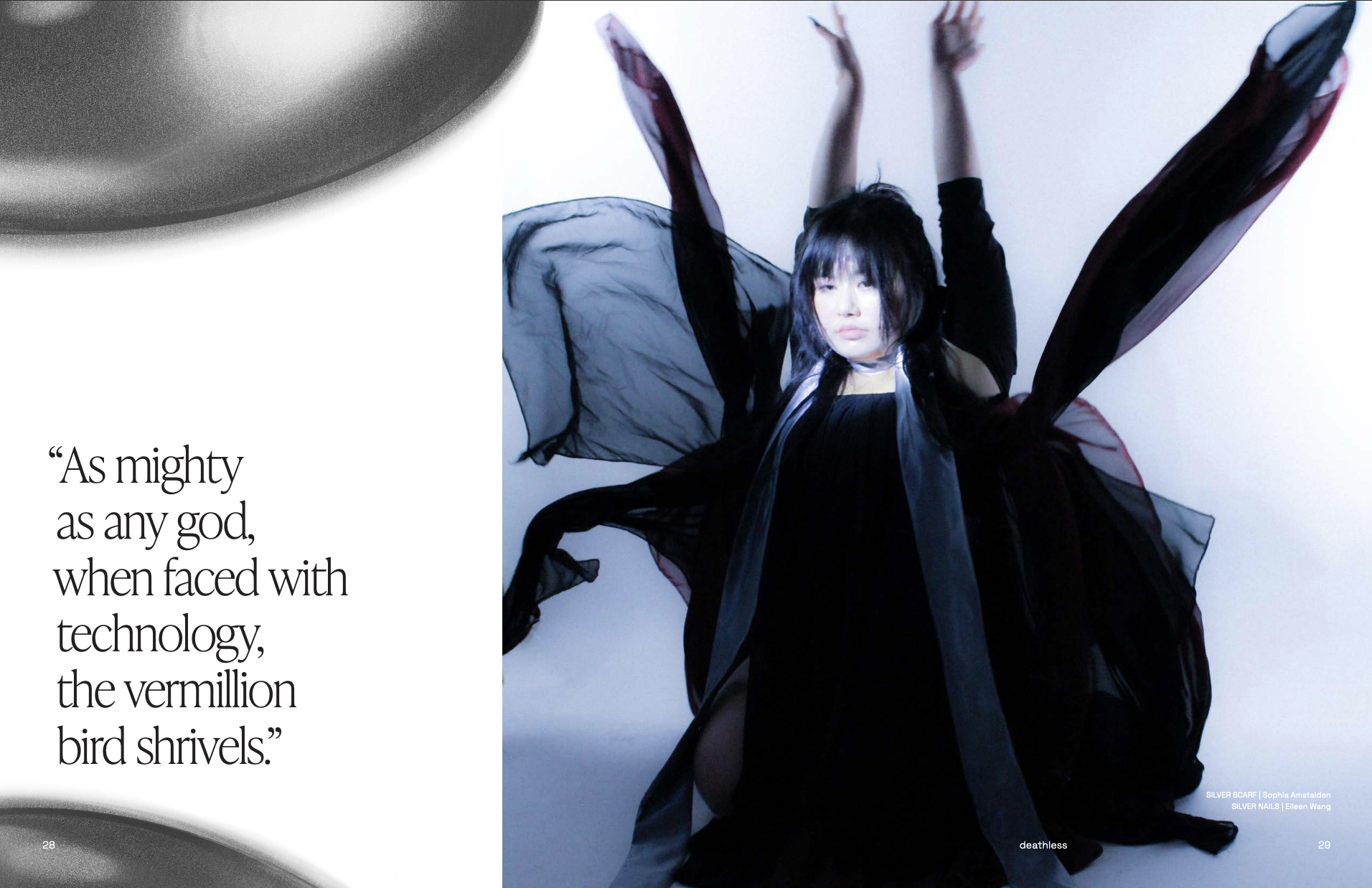

As mighty as any god, when faced with technology, the vermillion bird shrivels.

The hunter lifts her gun in victory.

Somewhere in one of the thousand villages dotting the coast, glittering sea brightly contrasting the drab and gray landscape, a widow with four children clutches her taser close to her chest. Besides the tattered blanket wrapped around her children, the taser is the last possession she has for protection. War is long and draining, both emotionally and financially.

“Will we survive?” one of the children asks.

The widow hesitantly nods. She wants to reassure them, but she’s not sure how. There’s a gaping hole in her, one she doesn’t know how to fill. No matter how much she grasps and searches, she still fumbles.

Sometimes, when the night is long and dark and smoke smothers all stars and the moon, she wonders if it’s always been so quiet and dull. She swears that her father’s voice, firm and hoarse, spoke tales of gods and dragons to her, but all the words she remembers are droplets of rain that don’t make sense together. The king dies, and the hunters rise to power: These are the proven facts, as irrefutable as the vermillion that never existed, that became a whisper in the wind.

Outside, a bomb explodes, and the widow drowns in her uncertainty.

In the middle of the Pacific Ocean, while the captain marvels at the hunk of metal designed to brave storms and rough terrains, a couple shivers in close pattern with the crashing waves.

The couple hugs each other. Eyes closed, hands clasped, and foreheads touching, they are determined to remember the country they have just left. It’s hard, though, especially since every breath they inhale tastes salty. A bit like their tears. A bit like the fear coating their tongues and brains.

The man is thinking about his mother, but in these turbulent, uncertain times, he feels sad that he can only remember the spinning machine. It spun and whirled a hundred times faster, produced more efficiently than ever, but he can’t recall exactly what his mom was weaving. In his memory, the thousands of pieces of fabric were nothing but a blob of color, devoid of individualism and culture. Click clack, plop and hiss: He wonders if there was a time when his mother listened to other sounds besides metal against metal.

Then, he wonders what he will bring to this new land.

“What will we give our children?” he asks his wife.

She lifts eyelashes to reveal dark, wet eyes. “I don’t know.”

* * *

To start from the beginning of the world means to start with mythology. Soaring above the human limits, beyond even technology, and fueled by hope and wonder, it is born out of uncertainty. The explosions of desire, the mystery of the unknown. Mythology at its core contradicts technology. Where one exists, the other cannot thrive.

When exhausted civilians retire from a day of tilling and harvesting, they look upon the pool of stars dripping down the night sky for comfort. They see two lonely souls desperate to reunite and the heavenly mother kind enough to weave the stars into a bridge. The sweat dripping onto the dusty grounds hints at the possibility of fruitless labor, but the warmly illuminated stars remind them of hope and solidity.

When tables are empty and white is all that can be seen, a weary mother hugs her sickly babies and remembers Tudigong, the Earth god. She’s already cried for the past two days, and the only reassurance left is that her baby will be taken care of in the afterlife. Gentle in appearance and nature, Tudigong embraces her agony and softens her raw edges.

This is the truth that people believe in when the tunnel is dark and the light is far. This is the truth that has achieved immortality. The branches of this ancient tree change and mold as societies and individuals evolve and adapt; however, the fundamental roots anchoring the trunk deep in the dirt remain the same emotionally and spiritually. Humankind’s belief in everything and nothing might disappear, but the remnants of stories that remain inside of them will last forever.

Societies are built from these remnants. A primitive giant cracks the chaotic world in half with his ax, and from his sheer strength comes the separation between yin and yang, land and sky, balance and creation. His statues stand tall and proud, full of purpose, duty, and responsibility. The Three Sovereigns, demigods at their core, use magic to improve lives and, at the same time, remind people of kindness and empathy. Lessons of courage and passion, virtue and loyalty: These leading principles become the foundations of human interaction and societal construction.

From these commonly accepted morals and ethics comes the establishment of law and order. The complex web that exists between mythology, culture, and value has become so intertwined and tangled that one cannot separate from the other without loosening the yarns making the string. Every interaction leads to another idea, which ultimately crosses the boundaries and dabs a hesitant foot into the creation of major belief systems that could go on to change the world. Destroy the massive pillars anchoring the roof to the floor, and the beautiful structures would subsequently collapse, too.

And when that happens, what will be left at the end of the world is rusting metal and toxic sludge. Technology gives people a sense of faux permanence. It comes in with its flashy gadgets and sweeps aside the shiny diamonds that have existed in minds for thousands of years. However, it will eventually erode and disappear, and the certainty it provided will burn to ashes. Left with no armor or shield, humans will end up struggling to grapple with the new reality, one where mythology hasn’t been provided a chance to grow and bloom into the protection it could be.

In one world, a lovely goddess and her pure white rabbit reside in a heavyset house gleaming a dark maple red under the brilliant light of the sun.

In another world, the telescope forces people to look up and see the uglier truth: craters, eroded rocks, and one dusty footprint. ■

Layout: Juleanna Culilap

Photographer: Jacob Tran

Stylists: Eileen Wang & Sophia Amstalden

HMUA: Meryl Jiang

Models: Tyler Kubeka & Tiffany Sun

Photographer: Jacob Tran

Stylists: Eileen Wang & Sophia Amstalden

HMUA: Meryl Jiang

Models: Tyler Kubeka & Tiffany Sun

Other Stories in Deathless

D>E>A>T>H>M>E>T>A>L

By Kunika Trehan

December 5, 2022

What if your wildest dreams came to fruition, only twenty years after you’d already forgotten about them?

Last night, I bore witness to the fresh seedling of a second chance. I stood one in a sweaty, eager sea of grungy adolescents ringing a vacant stage, peering over looming shoulders and tip-tapping my thumb against the thin strap of my bag. A thrum of anticipation hummed in the sparse air between us as we waited.

The crowd was young and eccentric, nodding heads adorned with cat-ear headbands and standing tall in thick-platformed boots. I was struck by the contrast when the band finally emerged, a collection of nondescript English men that had about twenty years on most of us. You’d almost believe they’d stumbled onto the wrong stage if not for the resounding cheer that erupted at the sight of them, the audience electrified by the reveal of a group once so shrouded in mystery.

Here, at last, was Panchiko.

“Good to see you’re all real people, too!” quipped frontman Owain as he looked out at us. The crowd responded with an uproar that carried an unspoken weight of understanding. We knew the serendipitous path of dissolution and resurrection that led them to this moment. It wasn’t simply that Panchiko’s fans loved them, or supported them, or streamed and shared their music for years to place them up on that stage.

No, it was more than that. They unearthed them.

-

Our path to excavation begins at the tail end of the twentieth century: cell phones are a luxury product; MP3 players are on the rise, but CDs remain in favor; and, in the U.K., Britpop is King.

In a teenager’s bedroom in Nottingham, a familiar scene unfolds: four school friends, armed with a Tascam digital recorder and boyish ambition, are recording a demo. They call themselves Panchiko, and they specialize in lush, lightly electronic 90s shoegaze. Cheekily, they name the album “D>E>A>T>H>M>E>T>A>L.”

They produce thirty copies of the demo and submit them to record labels for consideration, but to no avail. For a couple of years, they try their luck at the local music scene. They rehearse raucously in their drummer’s parents’ basement, one of the more soundproof spots they can access. They play sets to sparse crowds in local pubs, avoiding eye contact with their scattering of onlookers. They compete in “Battle of the Bands” competitions and lose each time.

Naturally, they’re having a blast.

But time keeps its pace and eventually catches hold of the boys, pushing them in opposing directions towards new sets of dreams. The original foursome plays their last show in a small-town festival to an uninterested crowd of onlookers and gently lay their dream to rest.

By 2002, Panchiko is no more.

-

But you’ve probably caught on by now that this story doesn’t end there.

In 2016, in a charity shop in Nottingham, U.K., Panchiko comes back to life— unbeknownst to its four founding members.

One of those thirty ill-fated demos has stood the test of time and sits resolutely well-worn on a shelf. The Japanese manga character on the album cover catches the attention of one shopper who picks it up and, unable to discern any further information as to its origin, purchases it and carries it home.

Intrigue deepens once they play the first song and find the audio is noticeably distorted: a fuzzy, static sound overlays the barely-audible melodic track. The CD, in its twenty-year recess, has been affected by disc rot, a condition affecting CDs over time that warps the audio quality.

Eager to discover more, our thrift-store archeologist picks up the CD and places it enthusiastically in the outstretched palm of the Internet. They upload it to 4chan’s /mu/ board, where music lovers from the depths of the web converge to trade in obscurities and conspiracy theories — the perfect breeding ground for a cult classic of the digital age.

The demo makes its rounds, trickling into various corners of internet subculture and growing a fanbase of its own. People are drawn to the music, which is experimental, clearly inspired by the late 90s shoegaze wave but featuring unique sampling methods and electronic elements that, paired with the distortion, make it sound almost retrofuturistic.

The origin of this long-forgotten disc is untraceable; no one has ever heard of the album, nor the band, and there is no record of them ever having existed on the Internet. The album’s back cover lists only the band members’ first names and the year of its origin. Online speculation runs wild.

No one is able to find another copy of the demo. Everybody wants an answer.

In 2020, they finally get one. It comes in the form of a one-word affirmation from Owain that this is, in fact, his band’s record, after a member of the Panchiko Discord group tracks him down on Facebook and sends the query. By now, the demo has taken on a life of its own; the band members that are still in contact with one another Google “Panchiko” and are shocked to find pages upon pages of forums and message boards dissecting their teenage dalliance with musicmaking. Messages from fans begin to flood in.

The following year, revived and reunited, Panchiko plays their first show in Nottingham in over two decades. There is no awkward smattering of applause this time; everyone has come here to see them. They play the opening chords to “D>E>A>T>H>M>E>T>A>L.” Once the cheering subsides, they are mirrored by a swaying crowd of their biggest fans, mouthing along to every word.

-

The awareness that something is tenuous, that your hold on it is circumstantial, that in any other alignment of events you may never have known it at all — this gives it value. The things we create may outlive our conviction to see them succeed; a dream doesn’t necessarily die alongside our belief in it.

“I’d find the CD every couple of years when we were cleaning out the house,” says Owain in a interview. He claims he’d think to himself, “thank god, I’m glad that CD isn’t on the internet.”

“D>E>A>T>H>M>E>T>A>L” has since been reproduced in CDs and vinyls, available to purchase on Bandcamp (“Pop it in a charity shop for 20 years for that crispy crunchy sound!”, the product description reads). It’s also been uploaded to streaming services. The Spotify version of the album features seven original tracks and four “rot” versions— transferred directly from that pivotal disc.

I find myself turning to these “rotted” tracks more often than their well-preserved counterparts. The first song of Panchiko’s I’d ever heard was the damaged version of “D>E>A>T>H>M>E>T>A>L,” recommended to me by a friend enmeshed in the world of online forums. I was, much like the others, intrigued by the mystery and entranced by the music, the distortion providing evidence to the mythos.

The rot appeals to the nostalgic in me; it’s as though you can hear the years on the track, physical proof of the time Panchiko sat idle. I listen and am embraced by the sentimentality of a time before my own, constructed by a group of teenage boys who held no idea of what the next few decades were to bring them. All they’d wanted was to make music.

-

Onstage in Texas, Panchiko begins playing “Laputa”, a wistful track inspired by Hayao Miyazaki’s “Castle in the Sky.”

The songs they sing were penned by teenagers in a bedroom twenty years ago, and hearing them in the flesh all these years later feels like catching a glimpse of a perfectly-preserved moment in the lives of four teenage boys I’ve never met but can picture so clearly through the sound.

Panchiko’s music exists in a unique liminality, bridging the gap in time between streaming-service supremacy and the CD age. “D>E>A>T>H>M>E>T>A>L” serves as a sonic time capsule: an album that made its way into the public’s ears over two decades after its inception, emerging into a wholly different musical realm and industry than the one it was born into.

The past twenty years have marked a massive shift in the way we create, distribute, and consume media. When Panchiko made their demo, the widespread popularity of streaming services was years away. Now, physical music is nearly obsolete. Records are retro and discs collect dust in bygone childhood bedrooms.

Now, the band croons years-old lyrics to a generation absolutely besotted with nostalgia for the early aughts, an era they can hardly remember — if at all. They find kinship in a set of adolescents who experience the world of music in a fundamentally different way than they once did. They prove how bendable, how entirely unpredictable this life of ours is.

In reviving their past, they split the future wide open. ■

Watch accompanying video here.

Layout: Sriya Katanguru

Photographer: Jacob Tran

Stylists: Miguel Anderson & Jeffrey Jin

HMUA: Alex Evans

Model: Saejun Smith

Videographer: Belton Gaar

Photographer: Jacob Tran

Stylists: Miguel Anderson & Jeffrey Jin

HMUA: Alex Evans

Model: Saejun Smith

Videographer: Belton Gaar

Other Stories in Deathless

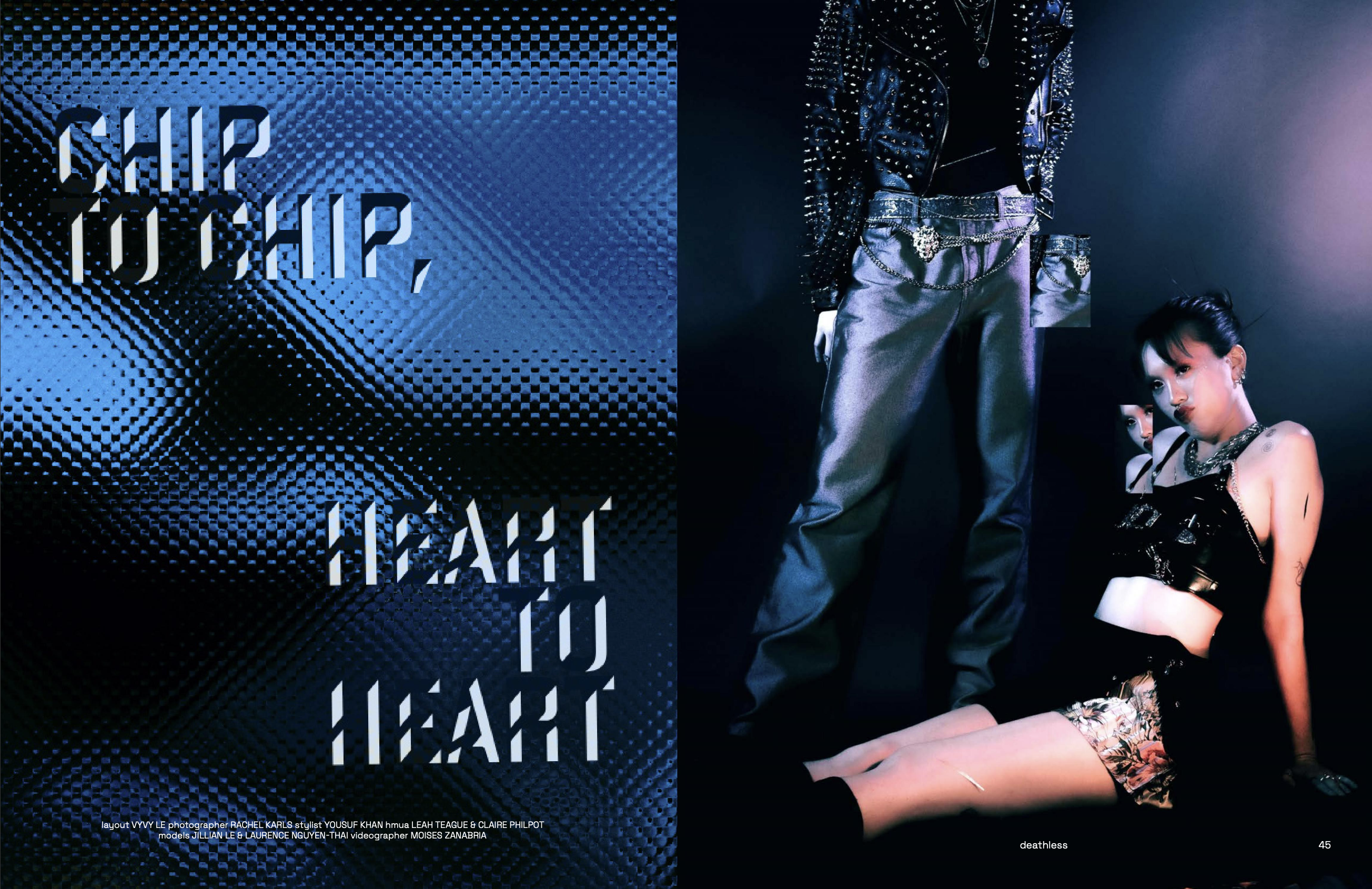

Chip to Chip, Heart to Heart

December 5, 2022

Layout: Vyvy Le

Photographer: Rachel Karls

Stylist: Yousuf Khan

HMUA: Leah Teague & Claire Philpot

Models: Jillian Le & Laurence Nguyen-Thai

Photographer: Rachel Karls

Stylist: Yousuf Khan

HMUA: Leah Teague & Claire Philpot

Models: Jillian Le & Laurence Nguyen-Thai

Other Stories in Deathless

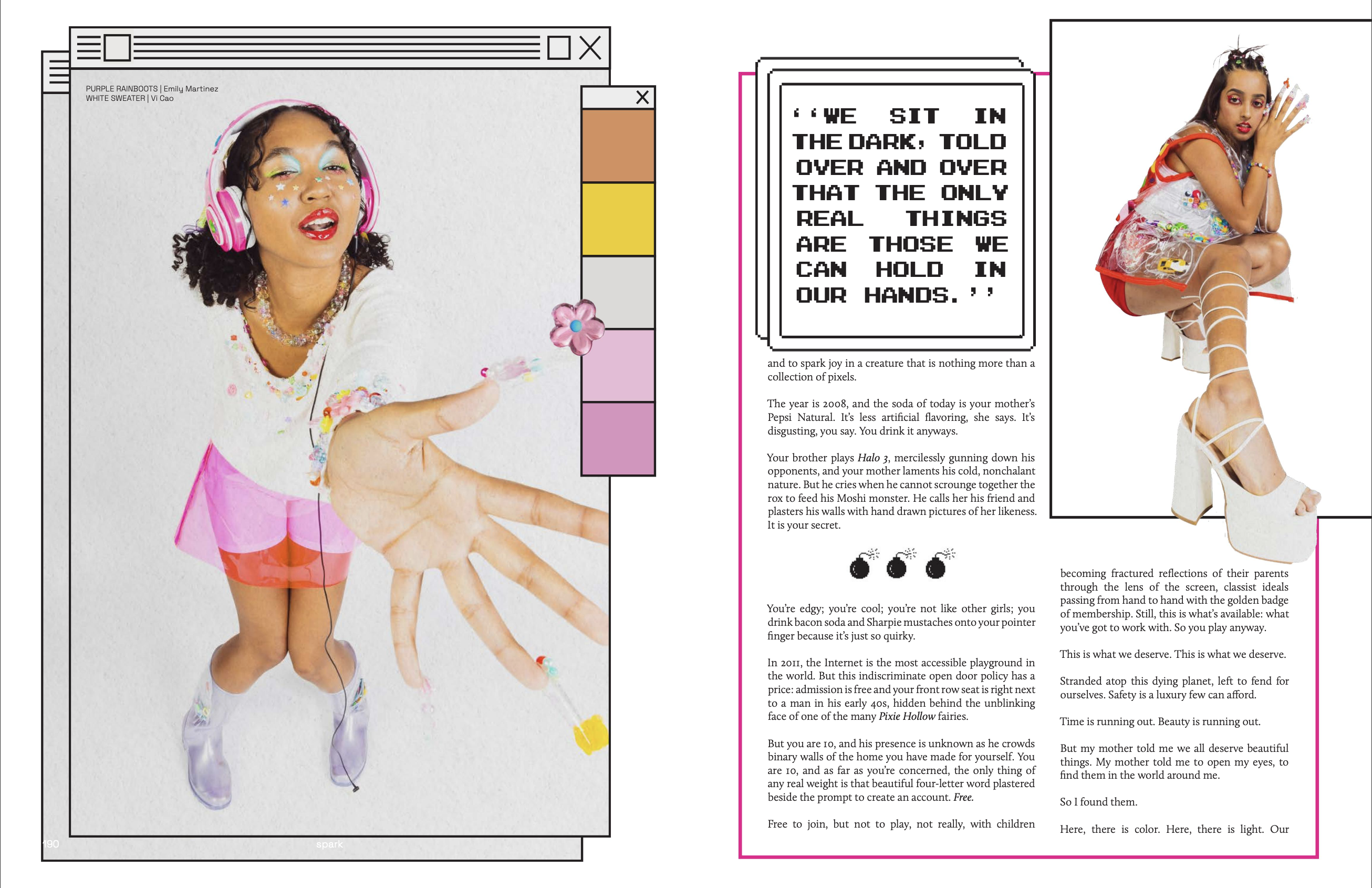

The Digital Playground of a Generation

By Bridget Beecham

December 5, 2022

For a generation raised on the Internet, the most accessible playground in the world is the MMORPG of the early 2000s. But with the digital depth of a previously unexplored landscape comes the guarantee of a childhood unlike anything we’ve seen before.

“You be the mom, and I’ll be the dad.”

“No, wait, I’ll be the mom, and you be the dad.”

Words exchanged, but not by mouth. Pudgy hands fly across the keyboard.

Pause.

Wait.

A text bubble appears, and you sit with bated breath as someone from across the world confirms that they would actually like to be the dog instead. It does not matter that on the screen, you are both penguins, or monsters, or whatever bizarre, colorful creature the site has chosen to populate its bounds, because this is your space, your comeuppance — your personal, virtual playground.

***

The basement lights are warm as you make quick work of the stairs, descending them in sets of two. From above, you can hear your mother distantly complaining about your heavy footsteps; her voice is pitched with disapproval. The television buzzes with the distant whine of the first-ever season of Rugrats, grating voices gracing the screen.

Still, you continue to pound your way down the stairs, a garish can of Surge clutched tight between your fingers, beads of condensation dripping down its thin aluminum walls. The year is 1991, and you are about to engage in some of the most exciting gameplay on the market to date: Neverwinter Nights.

The objective is fairly simple. With a design heavily reliant on the format of Dungeons & Dragons, the game before you on your brick of a Macintosh doesn’t stray far from the reality you already know.

And yet — and yet, as your avatar sways loosely, gaze unblinkingly meeting yours, it feels like more. Like an escape: a dream previously forged through spoken words and shared imagination now physically visible on your heavily pixelated screen. And you are happy to indulge, to don the armor of a paladin and ignore the jeering judgements of your mother. This is digital history, the first Massively Multiplayer Online Roleplaying Game, blinking to life on your computer.

***

Michael Acton-Smith says to be a child is to nurture, to care, and to cradle. In 2008, he creates Moshi Monsters. He talks about Tamagotchi. He talks about Furbys. He talks about pet rocks. They are the same, he says.

We are a desensitized generation, people say. And yet as we sit in the dark, told over and over that the only real things are those we can hold in our hands, we still want nothing more than to care. To feed and to clothe and to spark joy in a creature that is nothing more than a collection of pixels.

The year is 2008, and the soda of today is your mother’s Pepsi Natural. It’s less artificial flavoring, she says. It’s disgusting, you say. You drink it anyways.

Your brother plays Halo 3, mercilessly gunning down his opponents, and your mother laments his cold, nonchalant nature. But he cries when he cannot scrounge together the rox to feed his Moshi monster. He calls her his friend and plasters his walls with hand drawn pictures of her likeness. It is your secret.

***

You’re edgy; you’re cool; you’re not like other girls; you drink bacon soda and Sharpie mustaches onto your pointer finger because it's just so quirky.

In 2011, the Internet is the most accessible playground in the world. But this indiscriminate open door policy has a price: admission is free and your front row seat is right next to a man in his early 40s, hidden behind the unblinking face of one of the many Pixie Hollow fairies.

But you are 10, and his presence is unknown as he crowds binary walls of the home you have made for yourself. You are 10, and as far as you’re concerned, the only thing of any real weight is that beautiful four-letter word plastered beside the prompt to create an account. Free.

Free to join, but not to play, not really, with children becoming fractured reflections of their parents through the lens of the screen, classist ideals passing from hand to hand with the golden badge of membership. Still, this is what’s available: what you’ve got to work with. So you play anyway.

This is what we deserve. This is what we deserve.

Stranded atop this dying planet, left to fend for ourselves. Safety is a luxury few can afford.

Time is running out. Beauty is running out.

But my mother told me we all deserve beautiful things. My mother told me to open my eyes, to find them in the world around me.

So I found them.

Here, there is color. Here, there is light. Our house is on fire, and the only exit is the digital, so I take it. I jump from the second-story window, even if it hurts, because to jump is to breathe. Deeply. Fully.

Concrete is not so common in digital landscaping, so instead, we pick our ways through deserts and arctic tundras alike, navigating with arrow keys rather than our feet, the brain and the body disconnected and yet experiencing life with a vibrancy previously unknown. Color is so much sweeter from behind the screen of a computer as the fluorescent lights in the dingy school library brighten and dull, casting the walls with different shades of beige.

***

It is 2022, and there is something to be said for messages left on digital cork boards and moments shared on streets unknown to the physical earth beneath your feet.

The bleak monotony of my dorm could never compare to the garish interior decoration of my Club Penguin igloo. I sip Monster now. I bought it myself, and it tastes sweet. Ultra Sunrise.

It seems to me we are a generation of reflection, always looking back, always searching for something long gone. My domain continues to reside in the digital, never one for feeling the ground beneath my feet.

Real playgrounds are for the kids who grow up to tout their ethically superior granola childhoods to a TikTok following of thousands, kids whose bare feet were left unmarred as they glided down identical suburban streets, satisfied with their picture-perfect labyrinth of a neighborhood. All well-coiffed grass, tape-measured to perfection. Where the only concrete covers smooth asphalt roads, and the greenery is not limited to cracks in the sidewalk and the haphazard plants littering the steps of the old woman down the street (whose house stinks of butterscotch and resting home).

But for a moment I am 10, and any and all the free time I am afforded is spent using the family computer to play Moshi Monsters. I scoop ice cream; I save the day; I am unbothered and engaged in a manner of play previously thought impossible, but for me, it is second nature: second nature to log on and amuse myself with friends from halfway across the globe, second nature to do so in a sprawling world of ones and zeros with no price to act as gatekeeper.

An extension of the world I know already. I was raised for the Internet, and it was made with me in mind.

My space, my comeuppance — my personal, virtual playground. ■

Layout: Ava Jiang

Photographer: Mateo Ontiveros

Videographer: Liv Martinez

Stylists: Emily Martinez & Vi Cao

HMUA: Jessi Delfino

Models: Genesis Pieri & Nikki Shah

Other Stories in Deathless

© 2025 SPARK. All Rights Reserved.