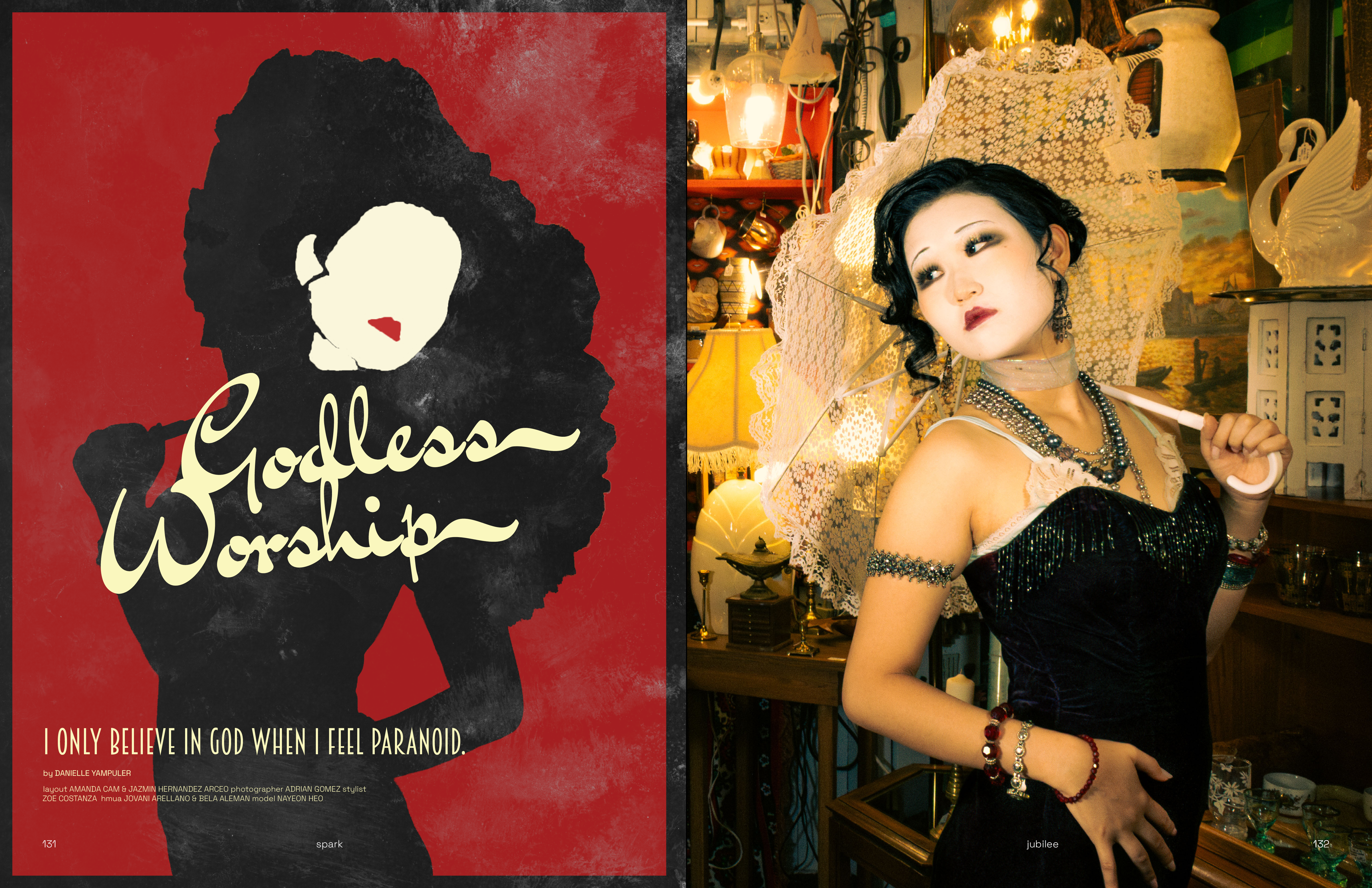

Godless Worship

By Danielle Yampuler

December 5, 2025

I only believe in God when I feel paranoid.

Small hands passed around a loaf of braided bread. Young voices sang prayer, “Baruch ata Adonai Eloheinu Melech ha'olam, hamotzi lechem min ha'aretz.”

The melody was odd but beautiful, as prayers often are. Not every child knew exactly what they were singing, but they felt its sentiments.

Thank you for our bread, each child thought as they took a slice of challah.

Just who they were thanking varied in their minds. Thank you to their teacher, who came with a loaf every Friday. To their friend, who chose to pass the loaf to them next. To the baker, who crafted this for them. And finally, as the prayer intended, thank you to God for making this possible.

There was an art behind the Friday tradition. It was not simply about having the treat, lining up for it as you would at a pizza party. Rather, each child served their classmates as a symbol of love, of altruism. I want you to have this.

In kindergarten, I was under the impression that faith and belief were a large game of make-believe. We all spoke in an ancient code. We chose to say we believed in God to communicate that we believed in kindness, morality, ourselves, and each other.

I believed faith was an agreement. Not one to God specifically, but to the world around us.

My parents were secular at best; I more or less escaped any structure surrounding religion when I switched from Jewish schooling to public. It was there that I realized many truly believed in God and his power.

One girl tried to baptize me with fountain water in a self-described attempt to save me from Hell. A boy taught me how to stick my middle finger up, then immediately proclaimed that I would go to Hell if I didn’t apologize to God every time I flipped the bird to the sky. I began to do so diligently, sometimes sticking my middle finger up so I could feel the relief of apologizing.

While God never made sense to me, I have always been well acquainted with the persuasive power of fear. As a child, I believed there were two men in my head who had the ability to blow me up if I didn’t do exactly what they wanted. Of course, I knew that they didn’t actually exist. However, if Bob and Larry said that I had to swim to the other side of the pool right fucking now or else my mom was going to get it, I was going to swim to the other side of that pool.

I’m accustomed to a sort of dual consciousness. There’s me, my actual brain. It is rational and knows that monsters aren’t real and that clicking the spacebar on my computer won’t make any difference in that. Then there is my obsessive brain. It believes that my boyfriend has been replaced by a demon in the four minutes it took for me to use the bathroom and return to bed, and that I must turn the light on to exorcise him.

The realm of demons these young children believed in was perfect fodder for my imagination. Who cares if Jews don’t believe in Hell? Definitely not me, because once the lights turned off, I had developed a million little rituals to keep the demons at bay.

I used to own a large teddy bear. Every night, I had to kiss it directly on its forehead twice due to an overwhelming feeling that doing so would stop something horrific from happening. However, I wasn’t great at keeping track. What if I accidentally kissed it 3 times? Demons knock three times to mock the holy spirit. Then I had to kiss it more, but what if the devil was coming to get me for kissing my teddy bear six times? No number felt safe. 9 is a multiple of 3, and 12 is a multiple of 6, and 13 is an unlucky number, and I would often end up kissing my teddy bear upwards of 20-something times a night. When I would finish, I never felt any better. What if I didn’t kiss my teddy bear the right number of times to earn protection?

I would wake up in the morning with an awareness that monsters didn’t exist and that my teddy bear had no magical qualities. I paid holy penance to it the next night regardless. I submitted to my bear in the way one would to God.

The issue is that the moment one submits to God, they must forever live in fear that they have not done enough for him. Yir’at shamayim. You fear God in the way you fear a parent: he nurtures and loves you, but also has the responsibility to punish you. Fear can be an agent of growth, or a parasite that festers in the mind, sowing seeds of distrust.

When I see preachers preoccupied with damning those they have never met to eternal agony, I wonder how often they lie awake at night, plagued by visions of fire and brimstone. I wonder if they lift their hands to their chest in prayer repeatedly, hoping to receive God’s protection. This frantic obsession with an entirely fictionalized reality almost makes me sympathize with them.

The difference is that I grew out of kissing my teddy bear.

I learned that my fear of monsters only strengthened every time my lips touched its soft fur. Completing the ritual perpetuated the cycle of fear, even in things I knew not to be true. The nights in which I was able to leave my bear alone were also more likely to be the nights I could stare into the dark without fear of what it might hold.

Simply reminding myself of something’s unreality was not enough to make me any less scared. My obsessions were brought on by anxiety, by a deep need for comfort. Compulsions satisfied that, but only ever in the short term. To move forward from my fear, I had to stop believing that my rituals had any use. I had to relinquish their power. Only then could I free myself from the anxious cycle.

Sometimes I wonder if that’s why I’m not religious: I can’t be. If I were to believe in karma, or God, or the stars’ magic, I would be pious. If I believed getting down on my knees made any difference in whether I would burn or not, I would live in an endless cycle of believing I have sinned and then begging for resolution.

Despite this, everyone needs faith. Something to believe in that keeps one foot moving in front of the other. I am not exempt from this. I may not believe in the mystical, but I know when I am having my own version of a divine encounter.

Every Spring, my mother insists that my sister and I return home for Passover. It is my family’s favorite holiday. This is an unpopular opinion among Jews: traditionally, a Passover Seder consists of 3 hours of prayer and small portions of bland, symbolic food.

My family enjoys it because we speedrun the seder in 30 minutes. This means we consecutively drink the traditional four glasses of wine in that time period. In between glasses, my mother explains to the table what the story of Passover means to her. God is rarely mentioned; she knows barely anyone at the table cares for Him. Instead, she encourages us to be thankful for what we have: our freedom, our food, the people we love.

Last year, 3 of my closest friends attended. After the seder, my sister played music. We stood up to dance, sneaking some more glasses of wine. I couldn’t stop giggling as we twirled around my mother’s living room.

In moments like these, I know where I put my faith. Looking into the eyes of the people I love as they clumsily spin me around reminds me that they are who I truly care for. God may not have been present, but it was a religious experience nonetheless.

I know I am falling into my anxious ways when I find myself fearing things I do not believe in. I still catch myself muttering God an apology when I point my middle finger upwards. In those small moments, a familiar and comforting fear takes over me. I feel God’s presence, and the heat of hell below me. I return to my agnostic state as soon as the apology is finished.

Afterwards, I remind myself that I prefer to put faith in things I know to be true. Things such as the love I hold for others and the love they hold for me. I believe in kindness and in ensuring everyone gets what they need. I believe in thanking the person who gave me my bread and then passing it along. ■

Layout: Amanda Cam & Jazmin Hernandez Arceo

Photographer: Adrian Gomez

Stylist: Zoe Costanza

HMUA: Jovani Arellano & Bela Aleman

Model: Nayeon Heo

Other Stories in Jubilee

© 2025 SPARK. All Rights Reserved.