Lucidum

December 5, 2025

Layout: Jazmin Hernandez Arceo

Other Stories in Jubilee

ode to hiraeth

By Anastacia Barbie Chu

December 5, 2025

I.

At last, a shrill ring pierces the air,

and chatter spills back into the room.

Tote trays slam into desks,

And I fumble with the laces on my pink converses.

Lines form; bubbles pop between lips.

Hushes silence the room, earnestly trying to mitigate the inevitable chaos.

Doors burst and GO!

Blazing sunlight blinds us,

A dozen fawns darting towards the jungle.

Whistles shriek as peregrines with lanyards

purvey the scene of wild kits running amock.

We all scurry toward the swings,

And I smile with pride settling into the plastic

Screaming at my friends to join me.

We swing our legs faster, and faster —

Soaring into the air in tandem

“You’re going to get married!”

my classmates cry, clutching the swing’s rusted poles,

giggling and hollering,

All waiting anxiously for their turn

But for now, i possessed the seat

With a grin carved into my cheeks.

As the sun embraced me in its rays,

a breeze swooshes holding me in its chill,

Tickling my closed eyelids, brushing my hair

Taking me higher into the air: free and infinite

II.

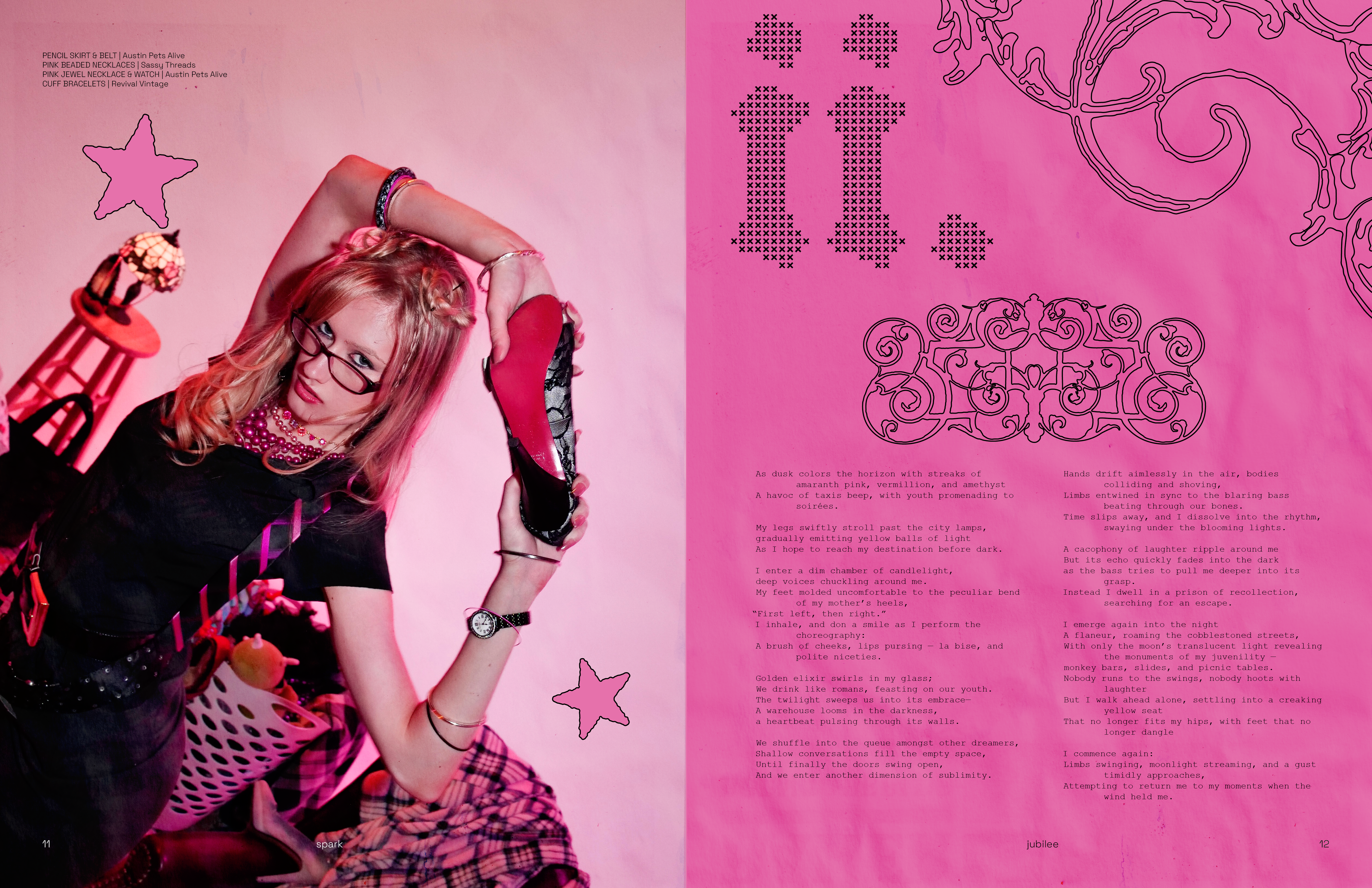

As dusk colors the horizon with streaks of amaranth pink, vermillion, and amethyst

A havoc of taxis beep, with youth promenading to soirées.

My legs swiftly stroll past the city lamps,

gradually emitting yellow balls of light

As I hope to reach my destination before dark.

I enter a dim chamber of candlelight,

deep voices chuckling around me.

My feet molded uncomfortable to the peculiar bend of my mother’s heels,

“First left, then right.”

I inhale, and don a smile as I perform the choreography:

A brush of cheeks, lips pursing — la bise, and polite niceties.

Golden elixir swirls in my glass;

We drink like romans, feasting on our youth.

The twilight sweeps us into its embrace—

A warehouse looms in the darkness,

a heartbeat pulsing through its walls.

We shuffle into the queue amongst other dreamers,

Shallow conversations fill the empty space,

Until finally the doors swing open,

And we enter another dimension of sublimity.

Hands drift aimlessly in the air, bodies colliding and shoving,

Limbs entwined in sync to the blaring bass beating through our bones.

Time slips away, and i dissolve into the rhythm,

swaying under the blooming lights.

A cacophony of laughter ripple around me

But its echo quickly fades into the dark

as the bass tries to pull me deeper into its grasp.

Instead I dwell in a prison of recollection,

searching for an escape.

I emerge again into the night

A flaneur, roaming the cobblestoned streets,

With only the moon’s translucent light revealing the monuments of my juvenility —

monkey bars, slides, and picnic tables.

Nobody runs to the swings, nobody hoots with laughter

But i walk ahead alone, settling into a creaking yellow seat

That no longer fits my hips, with feet that no longer dangle

I commence again:

Limbs swinging, moonlight streaming, and a gust timidly approaches,

Attempting to return me to my moments when the wind held me.

III.

My vessel lingers in this flicker of the present,

Yet my mind my mind roams the fragments of what was—

dollhouses, yellow swing sets, and ice-cold popsicles.

When life extended beyond temporal bounds

And tomorrow could not arrive soon enough.

I seek refuge in my vast analogue of yesterdays,

Donning princess dresses instead of pencil skirts,

When unknowing was innocent and curiosity was enticing,

Knowledge not yet a burden, and time moved too slowly.

I idle in the moment, sifting through the soft vortex of memories.

The present eludes me, fleeing far before my fingers can grasp it.

I no longer wish to merely exist, suspended in a quixotic continuum—

I ache to live and play, connecting the junctures of past and becoming,

Emerging free, cradling nostalgia while embracing the tangible. ■

Creative Director: Vani Shah

Layout: Brandon Porras & Emmy Chen

Photographer: Reyna Dews

Videographer: Larry Liu

Stylist: Zyla Alaniz

HMUA: Vani Shah

Model: Savannah Hilliard

Other Stories in Jubilee

AQUAMARINE

By Hana Robson

December 5, 2025

I tried my best to be the girl I was by the sea while I was stranded on land, but I couldn’t ignore the feeling swirling in my stomach. I secretly believed, in my heart of hearts, that I was a mermaid.

Swimsuit lycra smells like my childhood.

When my family made the six-hour drive to our ramshackle beach house off the coast, I came alive. I spent every waking minute from March to September in my swimsuit. I would dive deep underwater — so low that my ears would pop — just to see if I could touch the bottom of the deep end. I loved the floaty feeling of being completely submerged underwater, of being alone in my own small blue world. The salt water curled my hair, and I didn’t mind the sand between my toes if it meant a day spent at the beach, diving into the turquoise waves over and over and over again.

Leaving always broke my heart. Seeing my dad’s truck loaded up with boogie boards and sand pails meant that I would go back to school, and the dead brown grass that covered the playground. While the other girls played kickball, I sat alone and studied the movements in the clouds. I preferred it; there was less chance I would overhear whispered remarks about how quiet or strange I was. My classmates had left me once bitten and twice shy, so I shrank away, keeping my voice low in hopes of being unnoticeable. As summer turned to fall, the sun set later and the colors of the world faded away. My real life felt so far from this miserable world of cold and concrete. I ached to be back on the shore, feeling the sun warm my back and the waves tickle my toes.

When I was twelve, I decided I couldn’t continue living in two separate worlds. I begged my mother to move our family to Malibu so I could become an Olympic surfer. She refused. I retaliated by covering my walls in pictures of the ocean. I wore seashell necklaces to school and dyed streaks of teal in my hair, even though it meant whispers of laughter followed me in the dimly-lit cafeteria. I painted my toenails electric blue and listened to Island in the Sun until my CD player broke. I tried my best to be the girl I was by the sea while I was stranded on land, but I couldn’t ignore the feeling swirling in my stomach.

I secretly believed, in my heart of hearts, that I was a mermaid.

Rationally, I understood that was impossible. I was old enough to know that Santa Claus wasn’t real, that the tooth fairy was actually my parents, and that I shouldn’t run around telling people on the playground I thought I was half-fish unless I wanted an extended session with the school counselor. But some desperate part of me still practiced swimming with my ankles pressed tightly together and combed through YouTube for video evidence of mermaids’ existence.

I met Zoe, a transfer student from California, in the seventh grade. She had long curls haloing her head that she never bothered to tie up for gym class, and she wore countless necklaces and bangles that clinked softly like sea treasures. She never noticed the other girls that would circle her like a shiver of sharks, razor-sharp remarks on the tips of their tongues. While I felt myself drowning in the presence of the others, she simply floated away, unaware of their presence. Zoe had more important things to worry about, like what phase the moon was in that evening.

Zoe noticed the teal streaks in my hair, and her eyes sparkled when she said, “I like your blue hair. I think it makes you look like a mermaid.”

I noticed then that one of her necklaces was a sand dollar. I smiled back.

From then on, we were inseparable. We swam together at the rec center pool on Sundays and took turns pretending to drown in front of the teenage lifeguards to capture their attention. She shared custody of her nail polish collection with me in exchange for my CDs.

Zoe accompanied my family on our annual beach trip the summer after seventh grade, piling into the backseat of my dad’s pickup. As soon as we made it to the house, we shed our flip flops and ran all the way down to the beach. We didn't stop until the waves hit our shoulders, salt air whipping in our hair. Finally, I was home.

Later that evening, in our homemade blanket fort, Zoe and I played a game of truth or dare. I asked if she had ever kissed a boy. She asked if a kiss on the cheek counted for anything. I said it probably didn’t.

“Do you ever worry that we’re falling behind with that sort of thing?” I whispered anxiously. Back then, my worst fear was always that I wasn’t growing up quickly enough — I had nightmares of my principal refusing to hand me my diploma because she found out I still watched cartoons and slept with stuffed animals.

Zoe paused for a moment as the question swirled in the air between us. “No, I don't really think about it,” she said, adjusting the pillows behind her sleeping bag.

“What do you mean you don’t think about it?” I asked, bewildered.

“I mean, I just don’t care all that much. I care more about hanging out with you than I do with boys. Maybe one day that will change, but I don’t see a problem with it. Anyway, why care about what anyone else is doing?” I felt my cheeks start to go bright red.

“Besides, you're a lot more fun than boys are. They all smell like Axe.”

I hit her over the head with a pillow in response, and she followed my lead. We didn’t stop swinging until feathers flew into our hair, and our chests ached with laughter.

Emboldened by her recent confession, I chose dare next.

She grabbed my hand and jumped up. “Let's go swimming!”

“Outside? In the ocean?” I asked, confused by her sudden urgency. She pulled me out of our room and onto the porch.

I knew it was risky to go out on the beach after dark, but I followed her anyway. We stood on the shore, watching the stars twinkle against the waves, when she grabbed my hand.

“Come with me,” she said.

I hesitated. I was afraid of the dark blue water at night. I couldn’t see what lay beneath the murky waves. I felt her hand grasp mine and squeeze. She knew I was scared, and I could tell she wanted me to be adventurous for once, to fight the urge to hide. We slowly waded into the water together.

“We could swim all the way to San Diego,” she said before diving into the saltwater. I dove with her, feeling the cool blue wash away the sand on my skin. For a moment, I contemplated swimming into the depths of the ocean and never looking back. I felt the push and pull of the waves dragging me under, felt the pressure build in my lungs as I swam. I wanted to escape into the ocean forever, to swim until I was far away from my anxieties. It was only when I broke the spell and surfaced for air that I realized Zoe was waiting for me on the shore, a smile on her face and a towel in her hand. There was no need for me to be anxious.

A year later, Zoe’s family moved back to California. Her dad got a job for some new-age tech company in the Valley. We promised to write each other, but with time, the letters dwindled into texts, which dwindled into nothing. She left me her sand dollar necklace, and for years I wore it every day.

Even though she was gone, I still saw her reflection in every seashell, in all the phases of the moon, and in the curl of every wave as it broke the shore. When I felt doubt in my thoughts, I imagined Zoe’s voice asking, “why care about what anyone else is doing?” I found that the more I pretended I didn’t care what anyone thought of me, the more I could stifle the whispers and the sideways glances.

Eventually, I didn’t even feel like I was drowning anymore, or that I needed to escape into the ocean. I could just float. ■

Layout: Elizabeth Kuromiema

Photographer: Abby Kerrigan

Videographer: Madison Ngo

Stylists: Sophia Marquez & Emily Martinez

HMUA: Karen Solis & Kennedy Ruhland

Nails: Anoushka Sharma

Models: Evania Shibu, Julia Corzo, & Amyan Tran

Other Stories in Jubilee

Painting and other mysteries

By Anjali Krishna

December 5, 2025

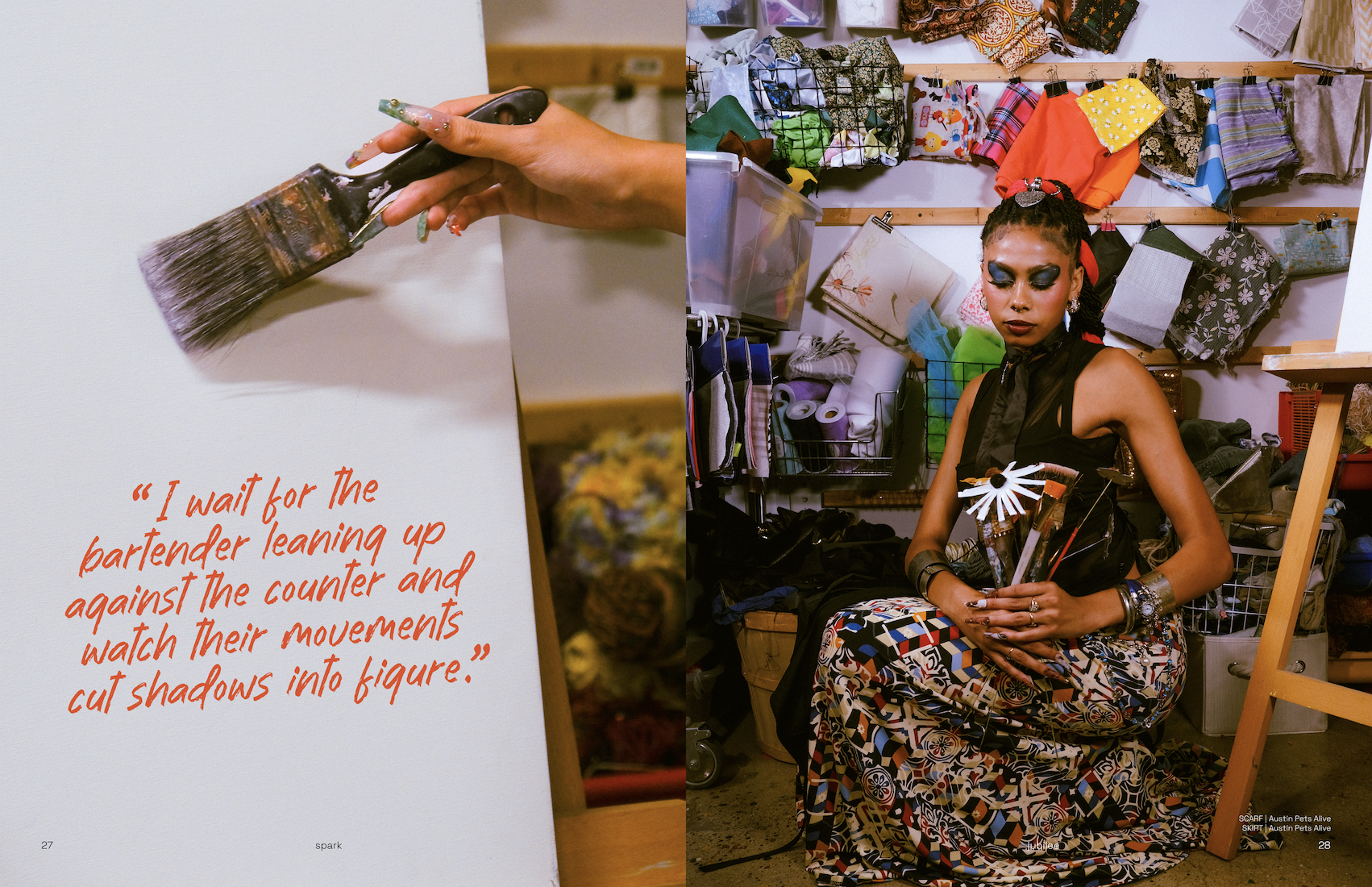

“What good does all the research of the Impressionists do them / when they never got the right person to stand near the tree when the sun sank?”

– Frank O’Hara, Love Poems

In the moments before close, the gallery is quiet. Only the noise of air conditioning whirs on with the faint sound of footsteps being rushed outside. I have a few seconds left before the attendant will fetch me too, tell me politely that the museum is now closed. For a bit, though, I have what’s arguably the best seat in the house—a cold black leather lounger in front of Jackson Pollock’s “One.”

Seated upright, shoulders back, I tilt my head one way and then the other. I send my gaze right side up and upside down. I trace the shapes in the paint splatters and then try not to read into them at all. I’ve already moved up close, studied the layers of material and shine. These details are written carefully in my notebook. On the seat now, I’m trying a different approach, hoping distance can offer clarity on why the painting matters. So far, distance hasn’t offered too much at all. Ungenerous.

I underline in blue pen beside the listed names of Pollock’s paintings, need to understand and analyze. I add a few exclamation points for good measure and leave before anyone comes to get rid of me.

In the window seat of the F train, I tap my foot to the rhythm of badly-fixed potholes hopped up on sugary raspberry tea. I count the stations as they go by: eight stops between 57th St. and 2nd Ave. There’s a drum performance — on an upside down Home Depot bucket — that I can’t decide if I’m supposed to like between the gaps of Joni Mitchell in my headphones.

Low-lit, white-hot in the heady summer air, I find my friends tucked into the corner of Tile Bar. I wait for the bartender leaning up against the counter and watch their movements cut shadows into figure. As Reva gesticulates, Jay and Ashrith shake their heads and laugh. It’s Thursday — the night is warm, spirits high.

I want a drawing of the moment, an image. But when I raise my phone to take a picture, I catch Jay’s eye through the camera and we both begin to laugh.

When the bartender gets around to me, he asks if I want the double vodka sour my friends are having. These days, this is the sort of thing which makes me happy: personal recognition from perfect strangers and my friends at our usual table. I sketch a smile and order another round, watching the soft hiss of the soda gun fill our glasses.

Lately Reva and I have been spending our hungover Sundays at the park, and I’ve been reading Frank O’Hara: the pocked-sized version Rhys got me before I left for New York. I think it’s in “To You” that he wrote “there’s no need for vistas we are one / in the complicated foreground of space.” Reva reads Dolly Alderton in the grass beside me.

Before the summer, I thought I knew a lot of things. I could tell you about the types of Classical columns (Doric, Ionic, Corinthian) and how the Umayyads co-opted Byzantine imagery. I could write essays about the ethics of repatriating the Benin Bronzes or what it meant to see curatorial diversity in contemporary shows. I inhaled facts from dark slideshows and spit them out on exam papers with a Youthful Leftist tilt. In the margins of my papers, professors wrote things like “deep insight” and “good point!”

On weekends in my apartment, I read interviews with famous authors before their first books and long-form articles about the cobalt mining in the Congo. These are the sorts of things that interest me, I liked to think before shutting my computer to talk with my roommates in the living room. Even then, I found the two worlds hard to balance — the reality which glowed so valiantly, or some other thing, a third dimension almost secular from my life where I read academic papers and produced novel comments about art and literature.

Before the summer, I searched poetry and painting for something missing in my life, that special, distinctive tissue of human connection. I searched in the bathtub, the BookPeople, and the dry spot between my thumb and pointer finger. I was obsessed with the details of other people’s lives: that they watched movies every Tuesday at Barton Creek Mall or had two best friends. I kept these facts in glass jars in my mind, dipping my fingers into them like honeypots when I wanted a taste of life and vitality. I had sought answers in analysis and facts, in things I thought would teach me the truth of life — whatever that might be.

Before the summer, I didn’t have the city as it moved with me and the friends I lived through it with. These days, I feel as frantic as O’Hara might have — “What good does all the research of the Impressionists do them,” he wrote, “when they never got the right person to stand near the tree when the sun sank”?

I have been trying, as of late, to write like O’Hara because it’s all that calls to me — our parks, our bars, our New York or Austin or wherever else. I don’t care for the avant-garde, the process, the analysis: I care for my life, our life, as it is in dialogue and text messages and the bar corner. I don’t care for the abstract expressionists because they never cared for you, for our life, because it is so obviously the best.

I have been trying to write and analyze and make facts of our life here, but I can’t make sense of it. I can’t make sense of it, and I can’t make sense of art that isn’t about our people and our lives because if they find something half as perfect as this.

—

Here it is, within my grasp just steps away. Here it is, mine and ours and theirs. The lantern-light shines through the windows at our bar and we are seated in the corner. Here it is, in the half-day’s light. Here it is, unspoken. ■

Layout: Emmy Chen & Sarah David

Photographer: Tai Cerulli

Videographer: Mo Dada

Stylist: Wen Wang

HMUA: Andromeda Rovillain

Nails: Alyssa Nguyen-Boston

Models: Da’Moni Babineaux & Isabella Leung

Other Stories in Jubilee

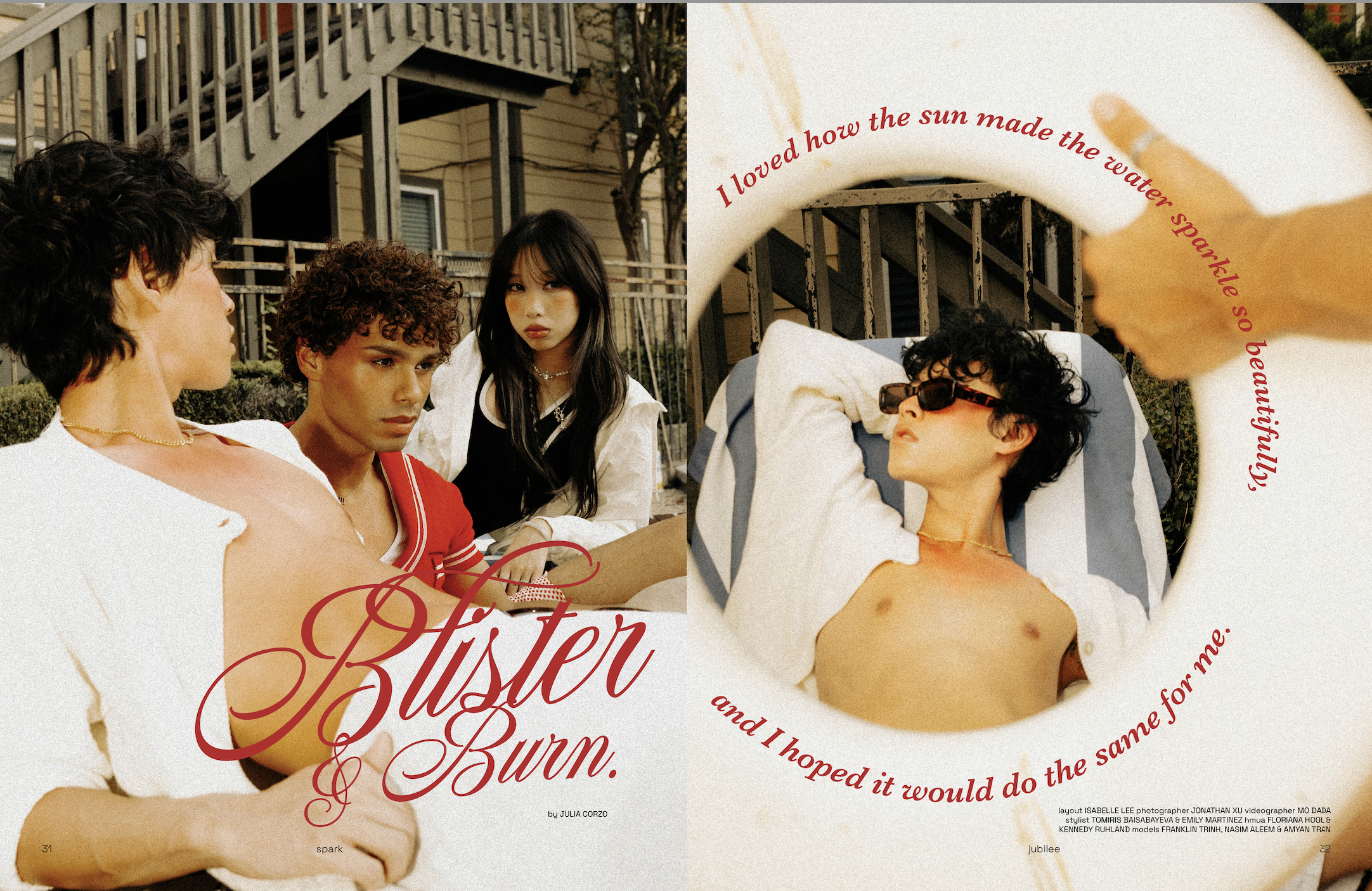

BLISTER AND BURN.

By Julia Corzo

December 5, 2025

I loved how the sun made the water sparkle so beautifully, and I hoped it would do the same for me.

As a child, I was told never to walk under the sun without protection, as it would be a disaster if I did. I never dared to ask what the disaster would be. I just knew that I should always hide from the sun, to “act like you’re too embarrassed to be seen by it.”

It was almost comical, the routine my mom would put me through whenever the temperature hit above 80 degrees and the sky got oh, so blue. Her ritual was predictable like clockwork.

It went like this:

1. Stand in front of her for five minutes as she lectured me about the dangers of the sun and how I should never look it in the eyes. If my skin became hot or heavy, I was to immediately return to her.

2. Turn around so she could spray my entire body with two very, very, thorough coats of sunscreen. Feel her hands rub my back raw just to “make sure it stays pretty.”

3. Face her for the same treatment on my face. Receive a quick little kiss on the forehead (score!) while she puts the last of the sunscreen on, smearing a white dollop on my nose extra hard.

As I grew older, I began to think I was above routines. They became a weight on my shoulders, an embarrassment I was not willing to take while all my friends tanned and bragged about the way the sun had given them such a sweet kiss.

I was tired of hiding in the shade. I wanted to step out into the sun.

-

One summer, I finally did. It was a beautiful day — the weather was above 80 degrees, and the sky was oh, so blue. My sister had just texted from her friend's pool to update me on her perfect tan. My sister belonged to the summer, turning a beautiful golden color under the sun and gaining the most lovely flush in her cheeks.

My mom liked to emphasize that I was a cooler beauty, prettier when the sun lost its powers and the shade made my eyes a cool grey. That day, I wondered why that mattered. The sun was right there, alluring and inviting.

I decided it was my turn to find that summer beauty, my turn to be kissed by the sun. For the first time, I decided to go without sunscreen.

As I eased myself onto the pool lounger and floated lazily around, I could feel the pinpricks of the sun on my skin. I felt powerful; the sun made me feel free. I loved how the sun made the water sparkle so beautifully, and hoped it would do the same for me.

The steady heat lulled me into a false sense of security, and eventually, I started nodding off.

I dreamt of skin like my sister’s, beautiful and glowing, basking in the attention of the sun. I thought of the tan the sun would leave behind — unnatural on my body, but even more beautiful. I dreamt of the compliments, of the attention.

Ever since I was a child, my mother would dress me head to toe in the “cutest” clothing she could find: adorning me with sparkly earrings and tying bows into my hair. I modified aspects of my body before I learned to do algebra. I was used to manicures, threaded eyebrows, and dyed hair.

Showing skin made me feel pretty. Having others look at me was an intoxicating feeling. Painting my face in makeup and glitter made me feel safe, like I was protected by something that would make me alluring, make me beautiful. I learned to like the eyes; I learned to love the compliments.

I dreamt of the feeling. I could feel the warmth.

-

I woke up two hours later and immediately knew something was wrong. I could feel the sun through my sunglasses, and there was a tingling sensation across my body I couldn’t quite name. I felt numb, disconnected from my body from the head down.

The first thing my mom did when I made my way back inside was laugh: she couldn’t believe I was stupid enough to sit outside for so long. When I asked her why she didn’t come get me, she insisted I could handle myself. She knew I couldn’t, though; the sunburn was just the perfect punishment for not listening to her years of warnings.

I rushed upstairs to the mirror. I watched as the burn began to take form, crawling up my feet to my thighs and sliding its way across my stomach. The burn crept up my chest and onto my face, where it comically avoided the spots my sunglasses covered. It felt wrong. It looked terrible.

I delicately peeled off my swimsuit and changed into something looser. I'd never felt the need to cover up my body so strongly. My skin had never felt so delicate, so fragile.

I wonder if this is how porcelain dolls feel. I hope my skin doesn’t blister.

My mother taught me that a sunburn was a death sentence — a slimy, slippery red snake that would curl up around me and leave me nothing like I was before.

I felt silly then. I wanted to chase something for myself, I wanted to uncover a new aspect of my beauty that I thought would make me unique. Instead, I was left with a mark of shame. It felt like a sick joke. I felt humiliated, and worst of all, I felt ugly.

After weeks of hiding behind drawn shades and blankets, I finally decided to go out with some friends. I spent hours in front of my mirror trying to cover the sunburn with endless amounts of concealer, desperately lathering it around my face, shoulders, and chest.

I felt like every person we passed knew I was sunburnt. They could see right through the concealer like an X-ray, looking right at the girl who flew too close to the sun, chasing something that was never hers to begin with.

A week later, I noticed a little white layer of skin growing over the redness. I was peeling. The peeling was calming, like watching the deepest source of my shame slide right off. I watched the burn soothe itself out and slowly fall off.

Watching the little white wrapping of skin gather together at different points across my body reminded me of the dollops of sunscreen my mom forgot to rub on me. I laughed at the irony, reveling in relief.

The pink of my skin began to take a stronger color, evening itself out into a rosy tone. The color reminded me of the moments before summer sunsets, when the sky turns a mixture of light blue and pink. I remember staring at myself in the mirror, thinking about how my skin resembled that soft, flattering light, even if it wasn't the golden tones of an actual sunset.

While I peeled, I went to California. The rolling hills of Santa Cruz and the cloudy weather felt like a refuge for me. Even though I was less pink, I was still sensitive. The clouds hid the way the sun made my burn look that much more intense, which made me feel less alien in my own skin. It almost felt nice to look in the mirror in the dewy hue of the morning and see a lighter color instead of my usual burning red. It looked beautiful in its own way.

I inspected myself in the mirror. I saw little bits of peeling skin left and the flush in my cheeks. My skin was still pinkish but also slightly golden. I’d never seen myself like that before, never imagined I could feel okay with the enveloping tingle of a burn all over my body.

I liked the way the golden-rosy color spread across my cheeks, down my chest, along my stomach. The coloring ran up and down my thighs, accentuating the muscle in my leg I had built while running from the sun, and to my feet, where it had already begun to fade out. That quiet, shady morning in Santa Cruz, when it was only me and the girl in the mirror, I felt genuinely beautiful for the first time all summer.

I never did get a real tan. I stayed rosy until September, until my pale skin finally pushed its way back, but I still have an outline of the sunburn in some places. I can still see the light outline of my bikini straps when I’m changing.

That summer, I discovered something about myself: that there is a version of me that can exist beautifully in the summer. I revel in the fact that even though I was set up to never find it, I did anyway. Even though the sun had barraged my skin and rubbed it raw, it still left me with a kiss goodbye. Maybe, just maybe, I’ll skip the extra dollops of sunscreen on my face this summer. ■

Layout: Isabelle Lee

Photographer: Jonathan Xu

Videographer: Mo Dada

Stylists: Tomiris Baisabayeva & Emily Martinez

HMUA: Floriana Hool & Kennedy Ruhland

Models: Franklin Trinh, Nasim Aleem, & Amyan Tran

Other Stories in Jubilee

© 2025 SPARK. All Rights Reserved.