Windows

By Katie Chang

December 5, 2022

As we turn to digital nature, what happens to our relationship with the real, physical thing?

My family never flies.

We’re the road trip type. The camping and eating freeze dried spaghetti kind of family. We drive for hours and hours on end, and I rotate between scrolling on my phone and staring out the window as one version of White Sands blurs into the next, on and on and on. The landscape seems to unfold endlessly—it feels like we’re making no progress.

There are 473k more pictures under #whitesands. I guess we aren’t.

***

For about 95% of our species’ existence, we survived as hunter-gatherers, in tune with the natural world. We knew we were at the mercy of nature’s order, and calculated our every action accordingly. We followed the ebb and flow of the seasons, navigating the land with the intent to survive—just as other species did.

At some point, some luck-of-the-draw combination of factors (a shift in environmental patterns, a larger brain, and a big toe, perhaps?) allowed for the development of agriculture, and from there, our relationship with nature changed. It was no longer something we were both a part of and subject to. We could interrupt the natural seed dispersal process to get more wheat! We could fence up a group of pigs to have readily-available meat! Nature became something to dominate, something to control to fulfill our needs.

As mud villages turned into concrete cities and human labor turned into machine, the same regard for nature that enabled our mastery of agriculture sowed the seeds of capitalism. Our wheat dispersal hack is now a billion-dollar fertilizer industry. Our pig pen is a trillion-dollar meat market. From the comfort of our leather desk chairs in our glass high-rises, we’ve cemented our role as nature’s puppeteer, and in doing so, we’ve sucked the life out of Earth’s soil and ripped apart its atmosphere.

Yet, somewhere deep within our psyche, we know we’re missing something. Somewhere not yet poisoned by the gospel of economic growth, our primordial affiliation with nature survives.

So, to recreate what we have destroyed, we turn to technology. “Digital nature.” Virtual reality is on the rise. Video games featuring mythical woods and majestic mountains are more popular than ever. We can experience an outdoor run via an indoor treadmill. We can explore pristine beaches and luscious forests via #nature.

And the best part? We get to create it all ourselves. With cameras and desktops that offer the newest and greatest computational abilities, we can make digital nature just like the real, physical thing.

But when we watch hiking vlogs or experience virtual reality, we can only see the river flow and the trees sway. We do not feel the wind or smell the soil. We hear the sky thunder and the bushes rustle. But we don’t have to listen, because we aren’t worried about a storm approaching or a bear lurking around the corner. We know we aren’t at the mercy of the nature we experience because we created it all — it's under our control.

And that’s the problem. Inherent to nature is the process of living in relation with the other, not in domination over it. Digital nature, as a human creation—a product of our utmost control—is not the same. It doesn’t even come close. Its very existence is contradictory to nature itself.

Our attempt to recreate what we have destroyed is not only futile—it’s destructive. Digital nature is an extension of the exact phenomenon that elicited its necessity.

***

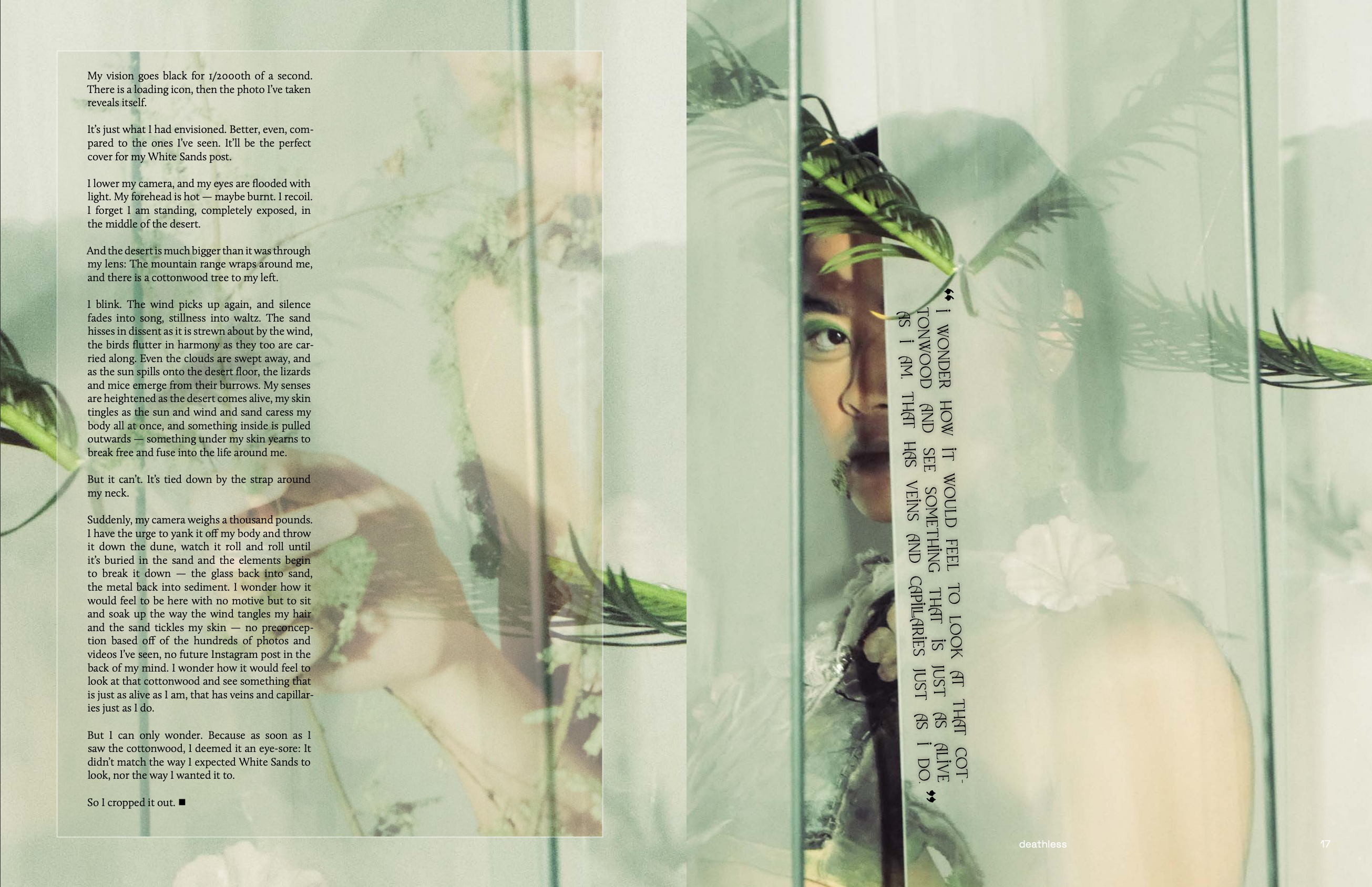

Smooth mounds of white gypsum blend into the painterly sky. The half-shrouded sun creates a soft glow over the deep blue mountains.

My vision goes black for 1/2000 of a second. There is a loading icon, then the photo I have taken reveals itself.

It’s just what I had envisioned. Better, even, compared to the ones I’ve seen. It’ll be the perfect cover for my White Sands post.

I lower my camera, and my eyes are flooded with light. My forehead is hot—maybe burnt. I recoil. I forget I am standing, completely exposed, in the middle of the desert.

And the desert is much bigger than it was through my lens: the mountain range wraps around me and there is a cottonwood tree to my left.

I blink. The wind picks up again, and silence fades into song, stillness into waltz. The sand hisses in dissent as it is strewn about by the wind, the birds flutter in harmony as they too are carried along. Even the clouds are swept away, and as the sun spills onto the desert floor, the lizards and mice emerge from their burrows. My senses are heightened as the desert comes alive, my skin tingles as the sun and wind and sand caress my body all at once, and something inside is pulled outwards—something under my skin yearns to break free and fuse into the life around me.

But it can’t. It’s tied down by the strap around my neck.

Suddenly, my camera weighs a thousand pounds. I have the urge to yank it off my body and throw it down the dune, watch it roll and roll until it is buried in the sand and the elements begin to break it down—the glass back into sand, the metal back into sediment. I wonder how it would feel to be here with no motive but to sit and soak up the way the wind tangles my hair and the sand tickles my skin—no preconception based off of the hundreds of photos and videos I’ve seen, no future Instagram post in the back of my mind. I wonder how it would feel to look at that cottonwood and see something that is just as alive as I am, that has veins and capillaries just as I do.

But I can only wonder. Because as soon as I saw the cottonwood, I deemed it an eye-sore: it didn’t match the way I expected White Sands to look, nor the way I wanted it to.

So I cropped it out. ■

Layout: Melanie Huynh

Photographer: Tyson Humbert

Videographer: Athena Polymenis

Stylist: Summer Sweeris

Set Stylist: Caroline St. Clergy

HMUA: Lily Cartenega

Model: Laurence Nguyen-Thai

Other Stories in Deathless

© 2025 SPARK. All Rights Reserved.